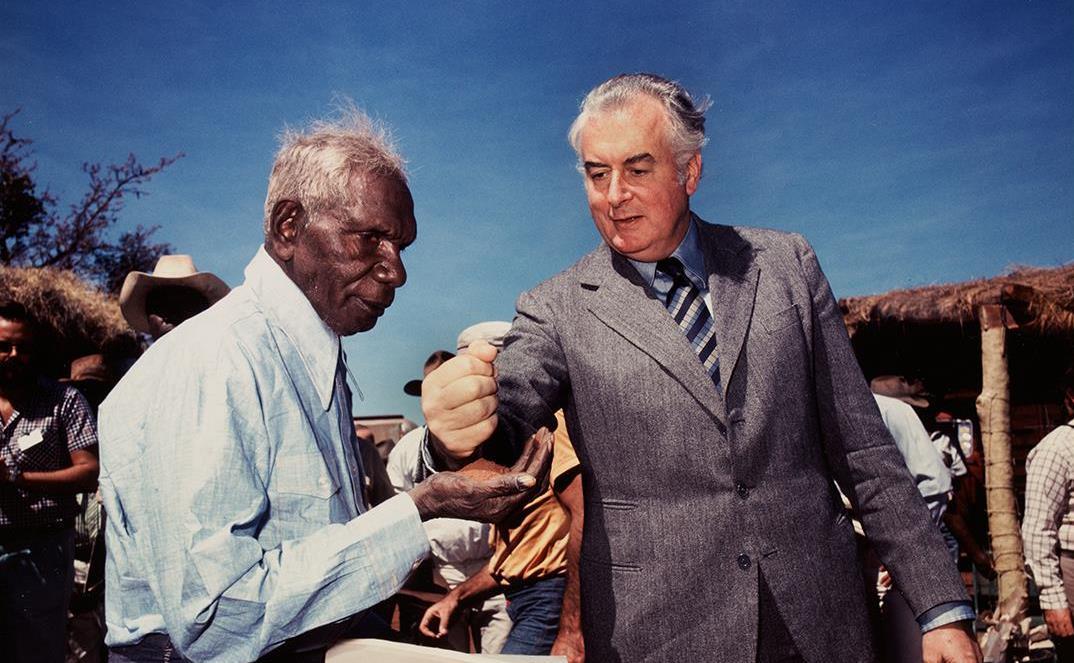

The photo is famous around the world, and rightly so. Taken by Aboriginal photographer Mervyn Bishop in 1975, it tells a thousand words. Against a bright blue sky, Australia’s then-Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pours a handful of red earth into the hands of Gurindji elder and traditional landowner Vincent Lingiari, marking the return of his people’s traditional lands.

The simplicity and eloquence of that image show Bishop’s craft and storytelling skill. While the original ceremony took place in the dull shadow of a tin shed, Bishop had the gumption and good sense to ask the PM and Lingiari to recreate the moment for the camera, outside against the blue. The iconic image was born.

That photo is just one of many on show as part of the Mervyn Bishop exhibition showing in Canberra’s National Film and Sound Archive from 5 March until 1 August.

Drawn from the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), and Bishop’s own private archive, it’s been enriched by audio and video created by the NFSA. Special features include a three-screen installation piece on boxer Lionel Rose; and a centrepiece half-hour documentary, Photographic Memory: A Portrait of Mervyn Bishop (1999) directed and shot by another great artist and visual stylist, Warwick Thornton.

‘Warwick’s film is a bit like the heart of the exhibition,’ says NFSA curator Tara Marynowsky, who worked with AGNSW’s Coby Edgar to create the AV elements around the photos.

‘The film is a really lovely piece that starts with Mervyn’s childhood and shows how he became passionate about photography and then developed his career. It’s also wonderful because he and Warwick had worked together in the past – Mervyn had done some stills photography on Warwick’s films, and on other people’s films, like Rabbit Proof Fence – and there’s a real intimacy to it.’

The exhibition features an installation featuring boxer Lionel Rose. Image supplied.

The exhibition features an installation featuring boxer Lionel Rose. Image supplied.

Now 75 years old and still holding slide nights, Bishop, a Murri man, was Australia’s first Aboriginal photojournalist and documentary photographer. Born in the small NSW town of Brewarrina in 1945, his father had been a shearer and soldier, and his mother was a passionate amateur photographer.

Young Mervyn began photographing family gatherings, friends and landscapes on his mum’s Kodak 620 camera, and became fascinated when a friend’s dad showed him the magic of dark room photo processing. He went on to become a young cadet photographer with the Sydney Morning Herald in the early 60s, and later worked with the Department of Aboriginal Affairs.

The exhibition showcases works that span this 60-year career, from the huge professional portfolio to home movies and family photos. What comes across is not just Bishop’s technical excellence (after all, he began in the era of black and white processing, when mixing chemicals in tanks was part of the job), but also his ability to move quickly and capture a moment before it disappears.

What also emerges is his humility and gentleness. As Marynowsky says, ‘He’s just a really warm and lovely person, a real gentleman.’

In Thornton’s documentary, Bishop admits that because of his upbringing he wasn’t schooled in Aboriginal lore. He says that while many activists wanted to enlist him in their causes, it wasn’t his place to be overtly political, just to do ‘a good job’ and record the facts. Movingly, he also talks about losing his wife Elizabeth to cancer in 1991 on the opening night of a big solo exhibition of his work.

Having co-curated the NFSA’s exhibition, Marynowsky says one of the things that excites her most about sharing his work is showing Bishop’s commitment to ‘the analogue side of photography.’

‘He has a deep love for the developing and the processing. It’s been a treat for us to show how photographs are made,’ she says. ‘We have a dark room set up in the exhibition and visitors are loving all the equipment on show, the enlargers, the cameras, the huge flash and his press equipment. Today everything’s digital and it’s really important, especially for school kids to learn about this history, and for us all to enjoy and celebrate it.’

The Mervyn Bishop Exhibition is currently on at the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia from 5 March – 1 August.