Image: www.acmi.net.au

A filmmaker delves into a real-life, high-profile murder case, his interest falling not with the purported perpetrator, but with the frenzy that played out in the press and the public perceptions such constant coverage inspired. In the feature that eventuates, another director follows the same trajectory, probing the chaos surrounding the legal proceedings, rather than plunging into the particulars of the suspected culprits.

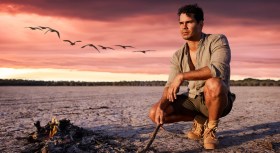

The first helmer is the ever-chameleonic Michael Winterbottom (The Emperor’s New Clothes), here making a movie based on the true crime book Angel Face, which compiled journalist Barbie Latza Nadeau’s writings on Amanda Knox’s trial over the death of her roommate Meredith Kercher in Italy. The second is Thomas (Daniel Brühl, Woman in Gold), who finds stimulus for his comeback feature in The Face of an Angel by Simone Ford (Kate Beckinsale, Total Recall), an account of the death of English student Elizabeth Pryce (Sai Bennett, TV’s Mr Selfridge) and the subsequent arrest of her American roommate Jessica Fuller (Genevieve Gaunt, Land Girls).

So it is that art imitates life in Winterbottom’s film, also called The Face of an Angel, as a filmmaker attempts to explore the act of adapting actuality to the screen by charging his protagonist with doing the same. Early in the movie, the helmer’s on-screen surrogate is told “you cannot tell the truth unless you make it a fiction”, a maxim the feature absorbs into its roving frames. It’s an intriguing move by the director, who frequently seems to weave his own pre-production thought processes into the final product, as set against fictionalised career, financing and creative troubles. It’s also an approach that endeavours to immerse viewers in a meditation on different mindsets, but sometimes proves distancing and disconcerting instead as it weaves visions and hypotheses into the narrative, as well as tussles with Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Of course, such a tactic ensures that the shifting, fleeting nature of actuality and justice comes across as it should, strengthened by the juxtaposition of aligning the audience with one person’s viewpoint while questioning the validity and objectivity of others. That’s Winterbottom’s point, as he works with screenwriter Paul Viragh (Ashes) to make plain, and as they both send Thomas careening through various degrees of affiliated parties – an opportunistic tabloid reporter (John Hopkins, Dancing on the Edge); another British twenty-something holidaying in the area (Cara Delevingne, Anna Karenina); a local blogger, landlord and shady type (Valerio Mastrandrea, Pasolini) – to learn.

Indeed, The Face of an Angel is both about perception and is shaped by it, with imagery to match. Once more, the filmmaker revels in contrast, cycling from the atmospheric Italian gothic of his primary Tuscan location, to the clinical glare of London-set business meetings, to the poetic fluidity of the feature’s many dream sequences. In fact, rare is the moment – or the method, including a lead performance from Brühl that veers from brusque to breakdown – that he lets pass by without underscoring the multiplicity of sides to his topic. Winterbottom’s film purports to be thoughtful and insular, an aim it achieves as it contemplates the consequences of conflating crime with entertainment and the inherent dangers of appropriating reality for creative endeavours; however it does so in the most broad and blatant fashion, mirroring the behaviour the movie strives to call out.

Rating: 2.5 stars out of 5

The Face of an Angel

Director: Michael Winterbottom

UK | Italy | Spain, 2014, 101 mins

Australian Centre for the Moving Image

www.acmi.net.au

4 – 16 June

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: