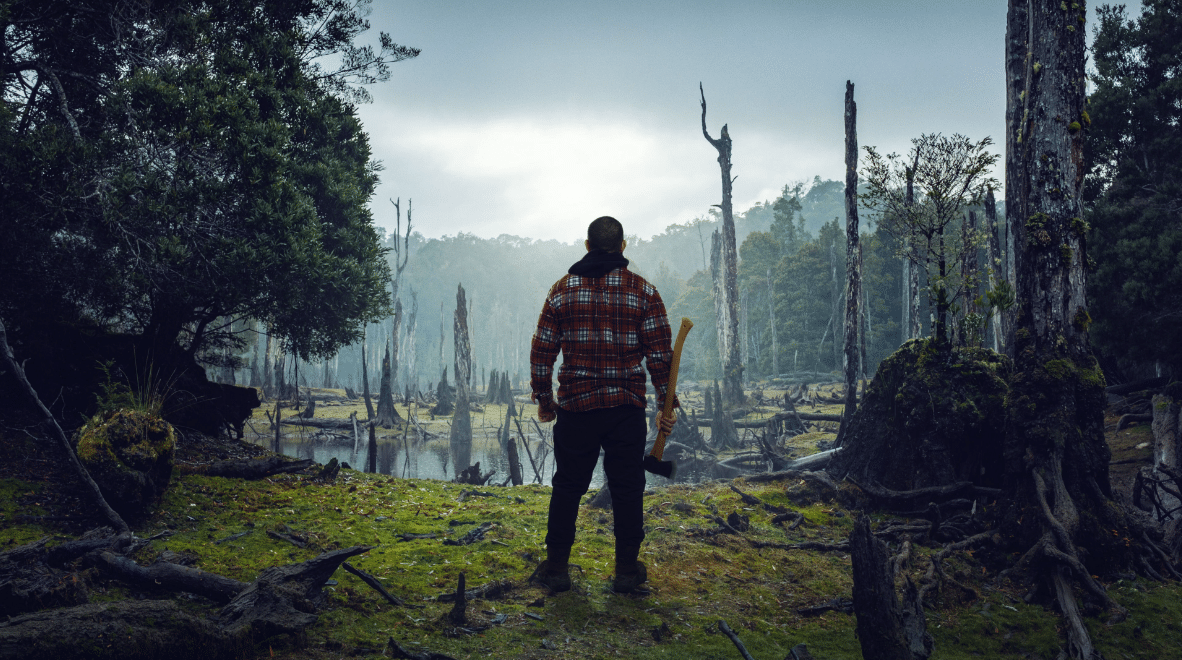

When SBS announced an Australian version of Alone, I just knew I’d dislike the kinds of swaggering wilderness experts such shows attract: Men, mostly. White, mostly. In their thirties or forties, extreme sportspeople or paranoid preppers. Gear-obsessed, maybe ex-military. Arrogant people who can only challenge themselves by dominating their surroundings.

This alone can’t sustain a show in which ten people with minimal gear are dropped into separate, isolated spots in remote western Tasmania, to see who’ll last longest.

Luckily, Alone Australia deliberately, persistently and humanely challenges the stereotypes of its genre – even to the point of questioning its own premise.

Read: Review: Safe Home on SBS

Self-knowledge is the best strategy

Alone Australia is a strategy game. Contestants can bring only 10 items from a pre-approved list. They must make their own shelter, hunt, trap and forage their own food, keep themselves safe… and film themselves doing it all, using supplied camera equipment.

The last contestant to voluntarily ‘tap out’ via satellite phone, or be disqualified for failing a medical check-in, wins a $250,000 cash prize. There’s no time limit; the longest winning stint in Alone’s history is 100 days in Season 7 (2020), set in Canada’s Northwestern Territories.

Its absolute solitude separates Alone from other survival formats. Contestants don’t compete against each other, but rather within themselves. And Alone Australia goes refreshingly low-key.

There is no host or voiceover to amp up the tension; instead, it unobtrusively but enjoyably weaves together observational storylines from the contestants’ fixed-position and wearable cameras. The story arcs are stuff like: ‘Will someone find food today?’ and let me tell you, I vastly enjoyed wolfing my dinner while watching a hungry person claim fried worms taste like bacon.

The show’s understated format means that we form parasocial bonds with the participants in very naturalistic ways. Their gregarious ‘video diary’ monologues never feel forced because we can sense their yearning for any kind of social interaction.

As the days pass, their initial bravado gives way and we glimpse, perhaps, their core values. Peter, a 31-year-old hunting guide from NSW, believes his tracking skills are his superpower. When he struggles to find game he quickly gets frustrated, complaining he’d have done better if he’d been allowed to bring his crossbow or gun.

Mike, 45, also from NSW, makes a living documenting his exploits as a ‘solo adventurist’ far from his wife and kids. He spends many episodes making tools and gadgets, but his painstakingly built kayak sinks the first time he tries to use it, and a pademelon constantly eludes his tripwire trap. Mike feels exasperated that he can’t solve his problems by throwing skills at them; but he resolves to stay patient and keep learning.

In early episodes I disliked Chris: 39, a hyperactive, jokey Iraq War veteran from Tasmania. But he became one of my favourite participants because of his acute self-insight and his unashamed vulnerability. When a meteorological survey helicopter flies overhead, we watch it trigger Chris’s PTSD flashbacks. When he plunges into low moods, he has the patience to wait them out – and he takes a touchingly pure joy in his successes.

Three contestants – Rob, Beck and Duane – are proud First Nations people who are keen to demonstrate their culturally acquired bushcraft skills. But their ties to family and Country are so strong that they suffer deeply from separation. Through them, Alone Australia subtly reminds viewers how cruel colonial violence has been in Australia. The trauma echoing through the Stolen Generations remains every bit as acute as Chris’.

Meanwhile, 41-year-old ACT wildlife biologist Kate also struggles to be so far from her wife and baby daughter. For queer Australians, family love is precious; being alone has political significance when a national plebiscite determines your right to marry.

Gina, 52, is a shrewd, practical rewilding facilitator who thrives on the show’s challenge. But quite a few episodes in, Gina reveals some deeply personal losses. She has hard experience in being alone; but she’s also acquired a resilience and wisdom other contestants have not.

Read: Independent film Echo 8 breaks the stereotype of the Australian immigrant story

Whose is the wilderness?

This rugged western-Tasmanian river country drove escaped convicts to cannibalism. It’s popularly understood as ‘inhospitable’: chilly, constantly rainy, miserable. But I was pleasantly surprised by how much Alone Australia resists colonial understandings of wilderness as a survival challenge.

Every episode begins by acknowledging the palawa people as the land’s traditional owners. So, too, do quite a few participants. Rob, a 41-year-old planning and environmental manager from Victoria, respectfully greets the land aloud in te reo Māori on his arrival at his campsite.

Kate has decided that for ethical reasons, she will fish but will not hunt, though she understands this might shorten her stay here. Like Kate, 35-year-old Duane works professionally with wildlife. Along with Chris and Gina – who loves to share her campsite with a visiting platypus – these participants perhaps express the clearest wonder for their surroundings.

Kate marvels at how different the ecosystem here is to those she knows. Meanwhile, Duane is alert for the sights and sounds of possums and birds, interpreting a visiting raven as a message from his wife. There’s some gorgeous nature photography in the show; I wonder whether it was shot by the contestants or the producers.

In a striking contrast, Michael, 43 – a vet, bush regenerator and devout Christian from NSW – prays to ‘Lord Jesus Christ’ on his arrival. To Michael, everything here is God’s creation, and even his own presence and abilities here are God-given.

Read: Totally Completely Fine on Stan: living on the edge

Onscreen captions add gentle contextual information at just the right moments. We learn how palawa people used this land: the plants and animals they ate; the shelter they built. Resisting the temptation to refer to it as terra nullius, the show reminds us that humans have thrived here.

However, I think it’s Rob who points out how artificial his situation is: only for entertainment would we make someone meet all their needs in an arbitrary place and season, with no help or company. (Indeed, in many First Nations law systems, exclusion from the community is one of the worst punishments.)

Colonial history is full of grim social experiments of the kinds we re-enact in reality shows. Just in Tasmania, two examples are the notorious Sarah Island penitentiary where convicts basically starved to death; and Wybalenna, the so-called ‘Aboriginal Settlement’ on Flinders Island where hundreds of palawa people died far from their own Country.

‘Wilderness’ is a Western construct, in which land exists either as a resource to exploit, or as a space into which to project individual sovereignty: ‘man vs. wild’ is deliberately antagonistic. This makes Alone Australia a rare TV treat because, paradoxically, it shows how much people need connection, community and curiosity to thrive.

Alone Australia is on SBS at 7:30pm on Wednesdays and all episodes are on SBS On Demand

Actors:

Director:

Format: Movie

Country:

Release: