Image: www.sff.org.au

Films about filmmakers are, in their nature, fraught with difficulty. Distilling the life and work of someone so familiar with the format down to just one instance of the medium they favoured is far from simple or easy. For most directors, their resume has already left an imprint over several movies, and capturing their essence and making a statement that exceeds their own is a feat unlikely to be achieved by a simple biopic. Perhaps, it is for that reason that Abel Ferrara chose to present his portrait of Pier Paolo Pasolini as something akin to a collage more than a traditional feature. His tribute to one of Italy’s most important and influential cinema minds, as simply titled Pasolini, is ostensibly set during the doomed auteur’s last days, but is more concerned with burrowing into his mindset than his final actions.

As such, the film presents a series of events of more significance to those familiar with Pasolini’s life than to those new to his tale. The director (Willem Dafoe, John Wick) writes a letter about his novel Petrolio, which was never finished, that Ferrara also uses as the basis for several scenes involving an enigmatic character named Carlo (Roberto Zibetti, Italian Movies). He discusses Porno-Teo-Kolossal, the next film he intended to make, and once more sequences – charting a man called Epifanio (Ninetto Davoli, All at Sea) – are weaved into the narrative. Pasolini also conducts interviews, reviews footage from his now infamous Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom during the battle over its censorship, spends time with his mother (Adriana Asti, Impardonnables), dines with friends, and searches the streets for companionship.

Indeed, Ferrara’s effort equates to a mood, personality and impact piece rather than a conventional look at the man or his legacy. A strong impression of Pasolini infuses each frame, as do slivers both of the filmic creations he was able to make, and the output he had conceived for the future; however style and performance is more crucial than the actual details. That’s not to downplay the painstaking research that obviously informs the feature, of course. In fact, after coming up with the idea with Nicola Tranquillino (writer of Tonino Guerra: A Poet in the Movies and an uncredited actor in 4:44 Last Day on Earth), and then enlisting Maurizio Braucci (Black Souls)to write the script, Ferrara could only make such an engrossing, elliptical portrait with a wealth of information at his disposal.

Stylistically, Pasolini drifts through and between its multi-lingual scenes as if flitting between dreams and memories, never lingering nor imparting a sense of permanence, as befitting the end already written in history. Though the narrative through-line binding the content isn’t always immediately apparent, it is instantly obvious that Ferrara has adopted the only approach that could have done his figure of interest justice. Watching shots fall on Dafoe’s face say plenty, and say more when juxtaposed with spiralling conversations, scenic drives through Roman streets, and the brooding recreations that form Pasolini‘s centrepieces by virtue of their comparatively lush nature. Indeed, Ferrara proves himself not only a master of both the sparse and the extravagant, but of weaving the two together, and of using the combination to speak to his subject’s sexual and political standpoints.

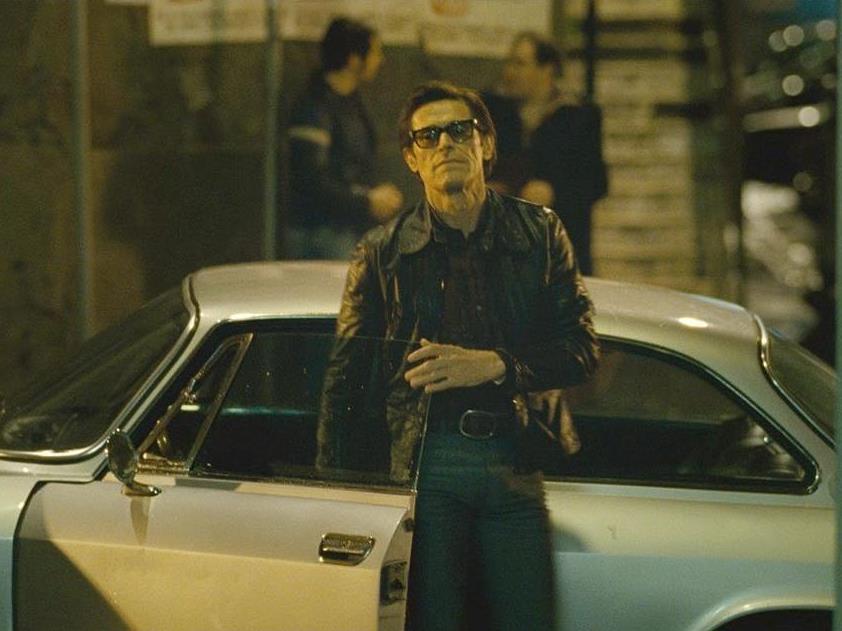

As he has shown in other efforts before, Ferrara is also adept in casting, with Dafoe given the role he was born to play. Though the veteran performer has many stellar turns to his name, including with this director, here he infuses his enigmatic real-life character with aesthetic cool and emotional eloquence, his portrayal less an impersonation and more an inhabitation. That he becomes the connective tissue that joins the feature’s many fragments is far from surprising. Though the knowledge Pasolini assumes of its audience remains its biggest stumbling block, Dafoe helps the film transcend the barrier between prior information and rendering the legacy of an imitable cinema icon as big-screen poetry.

Rating: 3.5 stars out of 5

Pasolini

Director: Abel Ferrara

France | Belgium | Italy, 2014, 86 mins

Sydney Film Festival

www.sff.org.au

June 3 – 14

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: