Imperceptible light and matter swirl in intricate harmony below the surface of everything we perceive. The atomic building blocks of photons, protons, neutrons, electrons and more, bound up in the ghost-like webs that connect them, are the source code of all creation.

But just as the rogue Titan trickster Prometheus stole fire from the cantankerous Olympians and bestowed it upon humans, who in turn used it to illuminate and extinguish lives, these elemental sparks can be torn apart, smashed together and then used to set the world alight.

‘If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once in the sky, that would be the splendour of the mighty One’.

Creation and destruction are inextricably bound in an infinite loop by this proclamation from the Hindu deity Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, predating the Greek myth. It is these words, and Krishna’s rejoinder to mortal soldier Arjuna: ‘I am become Death, destroyer of worlds,’ that infamously sprang from the lips of Dr Julius Robert ‘father of the bomb’ Oppenheimer, a student of the ancient scripture in its original Sanskrit, as he stood in the dirt of Jornada del Muerto (Dead Man’s Journey, talk about nominative determinism from the possibly prophetic Spanish conquistadors) just before dawn on July 16, 1945, while watching the sky burn.

Read: Oppenheimer – cheat sheet

Who, exactly, harnesses the destructive power of godhood has been drastically altered by these Promethean hands. Oppenheimer’s Manhattan Project team was worried that the ‘Fat Man’ bomb – set to raze Nagasaki three days after the simpler, smaller ‘Little Boy’ would annihilate Hiroshima – may not work, so they planned the fateful ‘Trinity’ test (a hat trick of creation/ death stories for the win) in the isolated deserts of New Mexico.

Tenet director Christopher Nolan invokes all this sturm and drang in his portentous morality play Oppenheimer.

Adapting Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s biography American Prometheus, Nolan deploys almost Aaron Sorkin-like rapid-fire dialogue to dash out the details of Oppenheimer’s eventful life in a film built upon the god particle creative paradox of what is seen and unseen.

Staring into the abyss

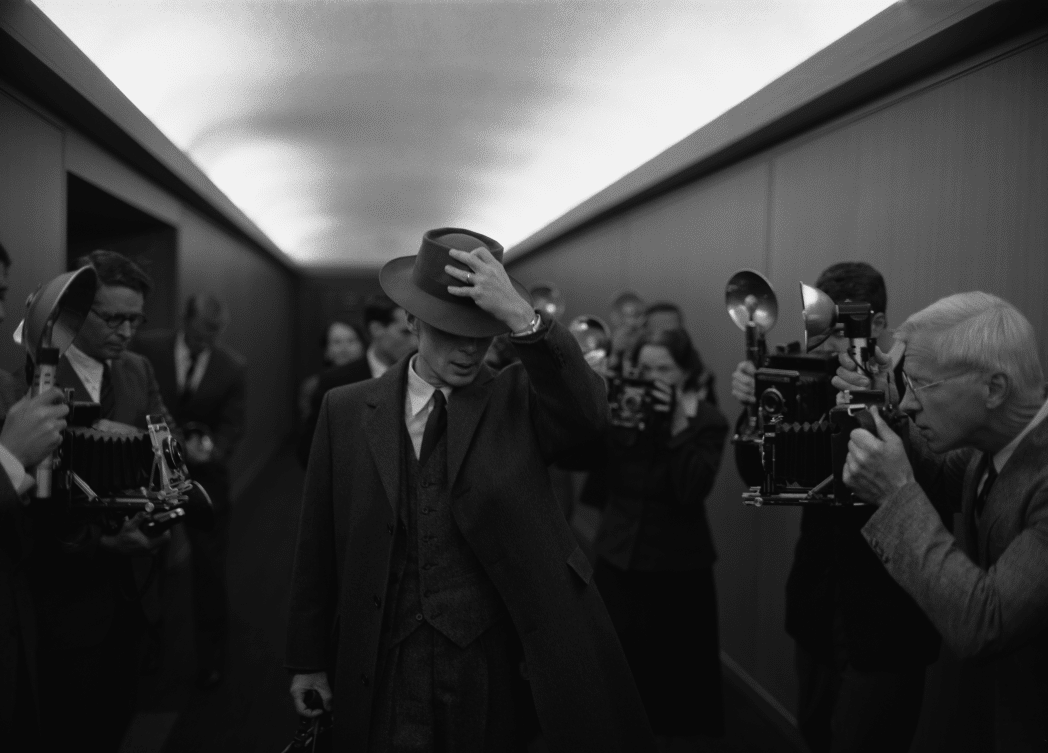

The contradictions abound, so it’s wise Nolan tapped Irish actor of cut-glass features Cillian Murphy as the haunted (to a point) theoretical physicist. A gifted actor with an innate understanding of restraint not always available to the Hollywood pantheon, he can hold multitudes in the almost indiscernible flicker of his face (admittedly easier to spot on Melbourne’s ginormous IMAX screen).

Nolan’s fondness for non-linear storytelling is less overt here, though more pronounced in the film’s visually and aurally arresting opening act, its strongest.

It intriguingly suggests that Oppenheimer is more tortured by the possibilities of the unseen world as a lonely student in Europe, grappling with the world’s minuscule but momentous mechanics, than in his elder days interrogated as a possible Communist traitor by shadowy extra-judicial forces led by a steely-eyed Jason Clarke as Roger Robb.

A real-life poisoning attempt on his demanding tutor with an apple is both very biblical and under-explored here, but Oppenheimer’s inner doubt and despair are caught in rain-lashed flashes, reflected in murky puddles that intertwine with ethereal sub-atomic lighting strikes that appear to crackle out of the darkness and into the audience. Hoyte Van Hoytema’s luminous cinematography casts a hellfire glare on the film’s haunted grey pallor.

Could it be that Oppenheimer had become so adept at compartmentalising the impossible decision he and his Manhattan Project team faced when racing the Nazis to weaponise Berlin’s discovery of fission?

Read: What to watch in July: new to streaming, cinemas and film festivals near you

It’s one of the film’s odd twitches that sometimes character is swept overboard by slavish devotion to complicated history, which is a shame given the mighty ensemble assembled here. Both Florence Pugh, as card-carrying Communist party member and psychiatrist Jean Tatlock, who had an affair with Oppenheimer, and Emily Blunt as his biologist wife Katherine ‘Kitty’, are sorely underutilised.

I really wish filmmakers like Nolan could figure out a way to tell women’s stories in such a way that they step out of the limitations of these oppressive eras without reducing them to glibly depicted alcoholism and depression.

Matt Damon shines as gruff Army general Leslie Groves, tasked with overseeing Oppenheimer and his wayward Manhattan Project colleagues, most of whom blend into the background, barring Josh Hartnett by the sheer dint of his screen charisma, too cruelly stalled by Pearl Harbour flopping (and yes, his presence here feels multiversal).

Tom Conti is a likeable Albert Einstein, sidestepping Oppenheimer’s date with dark destiny. Robert Downey Jr puts in his best work in years as Lewis Strauss, the former chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission whose nomination to the Senate by President Eisenhower becomes entangled with the question of Oppenheimer’s loyalty.

Solo star Alden Ehrenreich has a fun, if low-key, turn as his Sorkin-like political aide in these black-and-white sequences that speak to how inefficient a binary is when prosecuting the case for actions being good or evil in these circumstances. Though Nolan’s at times heavy-handed screenplay is at great pains to underline that Hitler had already fallen and Japan was almost certainly set for defeat when President Truman ordered the deployment of the twin bombs.

Eternal infernal flame

Speaking of which, the Trinity test sequence is spectacularly staged by visual effects supervisor Andrew Jackson, accompanied by special effects whizz Scott Fisher, opting for practical pyrotechnics over CGI as much as possible. The countdown is real edge-of-your-seat stuff, as is the blast itself, though the sound design here fizzles a little.

Which is odd, given Willie D. Burton’s work is excellent for the most part, and a vast improvement on Tenet’s inaudibility. Ludwig Göransson’s majestically menacing score helps sweep you into the maelstrom.

This fracture in history, forever tilting the world on its axis, will undoubtedly continue to be debated through the ages. Nolan may be a little too captured by the immensity of it all to fully deliver on the humanity of this horror, though no doubt a world of psychologist bills awaits his decision to cast his daughter Flora, who popped up in Interstellar, as the only overt radiation burns victim depicted in a nightmarish fusion of the Trinity celebration and the only-implied monstrous reality on the ground in Japan.

It’s an understandable decision, not to directly depict the obliteration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But as wise a choice as this probably is, you can’t help but feel it’s also emblematic of some of the cop-outs from sitting in consequence at play here. Murphy really isn’t allowed much time to show us the man behind the name, though it’s no fault of his impeccable performance.

A remarkable film, despite its foibles, like those neutrons, protons and electrons manhandled by (in)humanity, what is not here is as important as what is. Perhaps there’s no wrangling with this moment that can fully satisfy. Nolan, after all, is not god any more than Oppenheimer was.

Nolan’s latest epic is a work of self-professed importance that manages to be simultaneously over-stuffed and under-done, yet also, in several stretches of its never dull three-hour runtime, approaches the imperceptible sublime.

Oppenheimer is in cinemas from 20 July.

Oppenheimer

Director: Christopher Nolan

Date Created: 2023-07-20 02:00

4

Actors:

Cillian Murphy, Florence Pugh, Matt Damon, Rami Malek, Emily Blun, Robert Downey Jr

Director:

Christopher Nolan

Format: Movie

Country: USA

Release: 20 July 2023