‘Kurt Vonnegut told me once, we don’t understand the first thing about time …’

So begins Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time, a new documentary about the writer whose most famous work, Slaughterhouse Five, features the line: ‘Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time’.

Likewise, as viewers, we slide forwards to news footage marking Vonnegut’s death (from a head injury) in 2007, backwards to a 1970 TV interview with ‘a very funny and a very remarkable writer’.

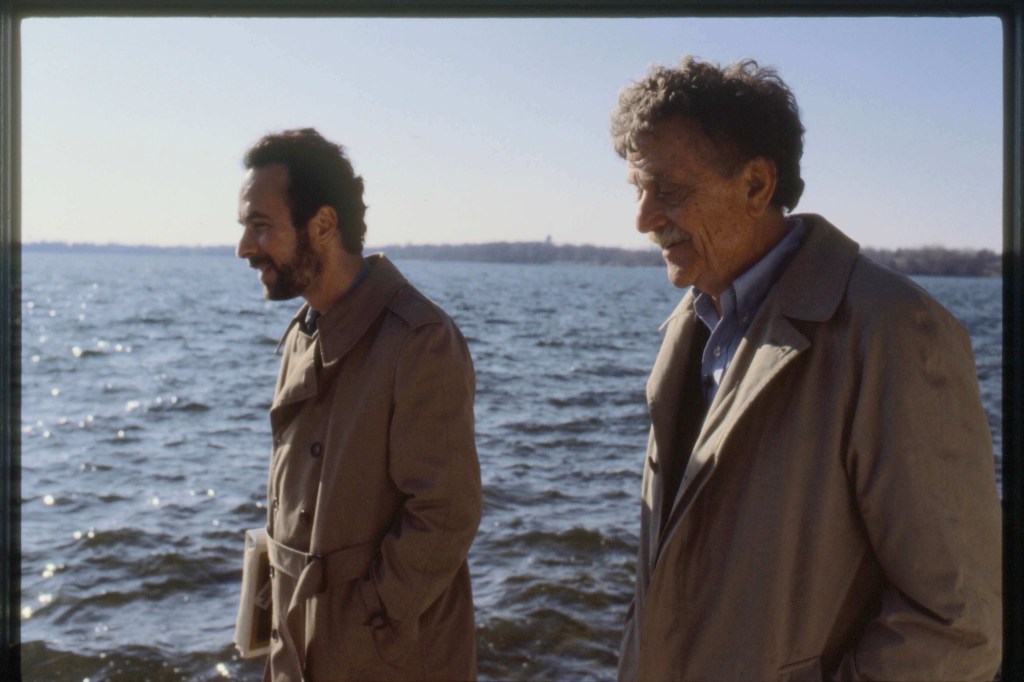

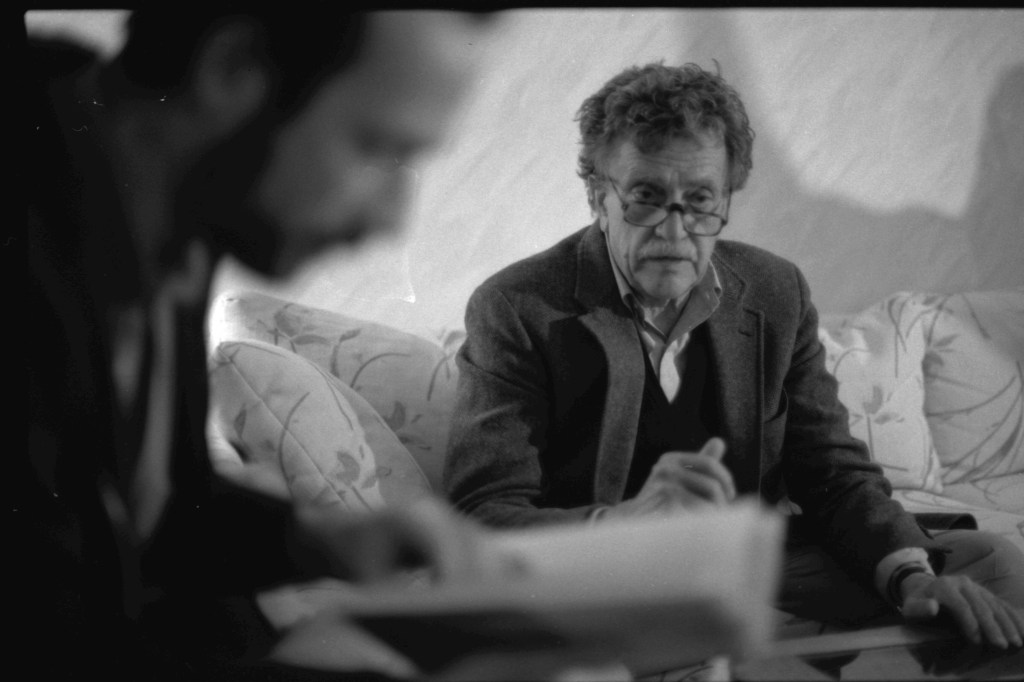

The chronological slipperiness works well not only thematically but practically for filmmaker Robert B. Weide, who captured Vonnegut on and off for last quarter-century of the author’s life.

We see the pieces-to-camera Weide intended as introductions to the documentary in 2014 and 2015 – the ‘stripy shirt interview’, the ‘editing room interview’ – and then another from 2017. ‘Every time, I thought it would be the last time,’ he explains.

He’d intended a conventional author documentary including interviews with Vonnegut’s family, biographers, publishers and scholars – all of whom bejewel Unstuck in Time. But given Weide was 23 when he first approached Vonnegut about the project, and is now 60, just as Vonnegut was at the time, the story is also about the process.

‘I don’t even like documentaries where the filmmaker puts themselves in the film,’ Weide says. ‘I mean, who cares? But when you take almost 40 years to make a film you owe some kind of an explanation.’

Weide needed to put food on the table, we’re told, whether through other film projects (including documentaries on comedians W.C Fields and Lenny Bruce) or as principal director and an executive producer of Curb Your Enthusiasm for the show’s first five years. All of which is fine, but Vonnegut fans will undoubtedly be keener to spend time with the author than the man he came to see as his de facto archivist.

From the archives

Intermittently, we’re shown restored 16mm black-and-white home movie footage of childhood Vonnegut with his well-to-do family, who tumbled from riches to rags during the Great Depression when there was no work for his architect father. We see his older brother Bernie as a boy playing in the garden and later, alongside his author brother, as a world-renowned atmospheric scientist.

We see Vonnegut as the baby of the family, literally looking up to his sister Alice, who he adored and who adored him. Alice’s death in 1958 – a couple of days after her husband was killed in an infamous train disaster – is posited (how could it not be?) as a major event in Vonnegut’s life. We see old and new footage of Alice’s four sons, who Vonnegut and his first wife Jane raised alongside their own children when they were orphaned.

From them, as adults, we hear how curmudgeonly and distant Vonnegut could be while they were growing up but also, on occasion, how funny and exciting he was – characteristics he melded into a persona that had audiences hanging on his every word at his public speaking events, many of which amounted to dispatches on the darkest elements of human behaviour wrapped in the wry humour for which he was known.

‘Laurel and Hardy gave me permission not to take life too seriously,’ he says in one interview. ‘They inspired me to try to write funny books.’

We gain insight (as we’d hope) into his writing process – the many, many drafts (typed out in the era before copy and paste) of Slaughterhouse Five (1969), the anti-war novel turned him from struggling writer to literary celebrity; the longer-than-expected gestation of its much-loved follow-up Breakfast of Champions (1973).

In a mildly confronting revelation (for those of us writing in the age of OHS concerns and ergonomic imperatives) his daughters Edie and Nanny demonstrate how he would write at a low coffee table in what was once his office, leaning over in a chair with his chest against his legs, virtually in brace position, to reach his typewriter keys.

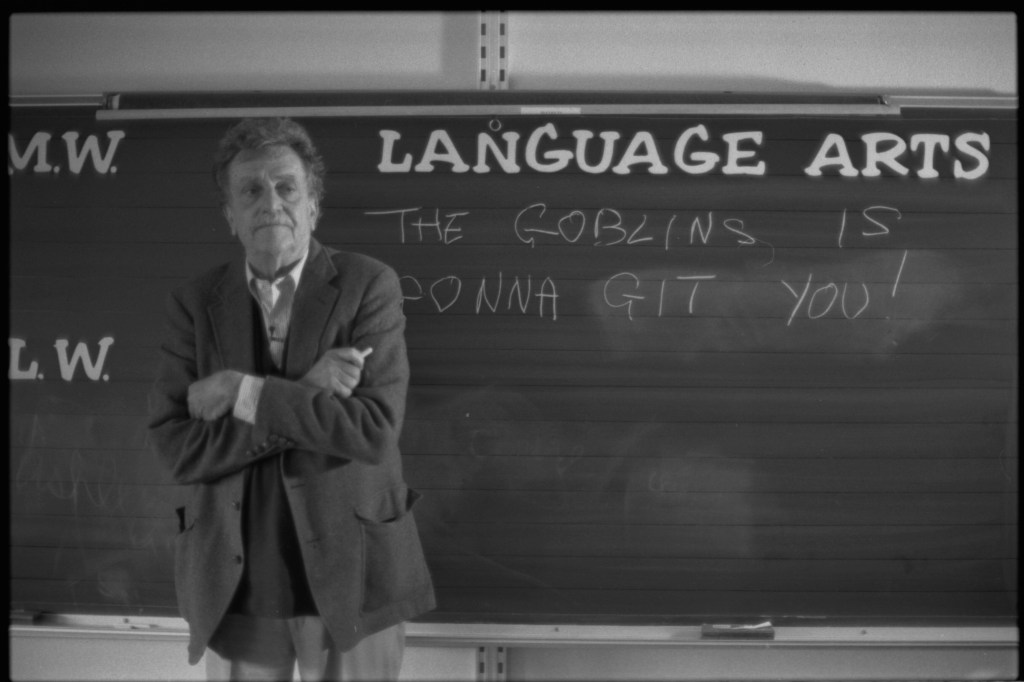

We also see him with Weide at his former high school, laughing as he recounts the ways the young men he knew at that time died during the Second World War – the one who died of spinal meningitis (a chortle); the other who was so excited about the Pearl Harbor attacks that he took a bath, smacked his head on the taps and died. It’s not a slight giggle either – he’s doubled over laughing. But why?

Set against news footage (and overlay from the 1972 Slaughterhouse Five screen adaptation), we hear the story of how Vonnegut, as a POW during the Second World War, sheltered underground in Dresden while the city was firebombed from the air and completely obliterated. When he and his fellow prisoners emerged, they had to dig adult and child corpses out of the smoking rubble.

When Weide suggests this must have had a profound impact on him, Vonnegut says:

‘It was a great adventure of my life and certainly something to talk about. I was there. But the neighbourhood dogs when I grew up had far greater influence on what I am today than the fire-bombing of Dresden.’

Unspoken trauma

It’s hinted at, though never overly so, that Vonnegut was traumatised by that experience, just as he was by Alice’s death and his mother’s suicide. As he says tellingly at one point: ‘I prefer laughter to crying.’

At 73, having written what he thought would be his last book, Timequake (1997), he retires from the public eye, becoming – as one friend puts it – ‘older, more cranky and falling apart’. At one event nearly a decade later, he jokes about taking a class action against the manufacturers of Pall Mall cigarettes. ‘I’ve been chain-smoking these since I was 14 years old and on their package they promised to kill me,’ he says to laughter. ‘I’m about to turn 83.’

As something of a believer in the American Dream, the two Bush administrations and their invasions of Iraq knocked the stuffing out of him, as summed up by his response to news images of Iraqi captives being marched along a road with their hands on their heads, just as he and his fellow soldiers had been as prisoners of war.

‘When I saw photographs of the Iraqi kids with their hands like this, having been shelled and bombed until they were half-witted, I said “those are my brothers”. I didn’t think it was amusing or wonderful at all to see kids in that situation.’

Partially in response, he started writing occasional, seemingly unpaid, essays and articles for a little US magazine called In These Times – pieces about George W. Bush, being a war veteran, and whatever else took his fancy. A small New York Publisher collected these and, after getting over his fear that his criticism of his country would backfire, Vonnegut agreed to them being published, hitting the bestseller list immediately as A Man Without A Country (2004).

In his typed response to Weide’s original letter explaining he’d like to film him, Vonnegut wrote:

‘There is sure no great footage to start with. Anything that is any good of mine is on a printed page, not film. Maybe you have some ideas as to what to do about that. I don’t.’

Weide does indeed have some good ideas what to do about that, as this documentary shows, even as we’re reminded, time and again, that the best of of Vonnegut is, and always was, on the page.

Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time, distributed by Madman Films, is in Australian cinemas from 7 July 2022.

Actors:

Director:

Format: Movie

Country:

Release: