Image: miff.com.au

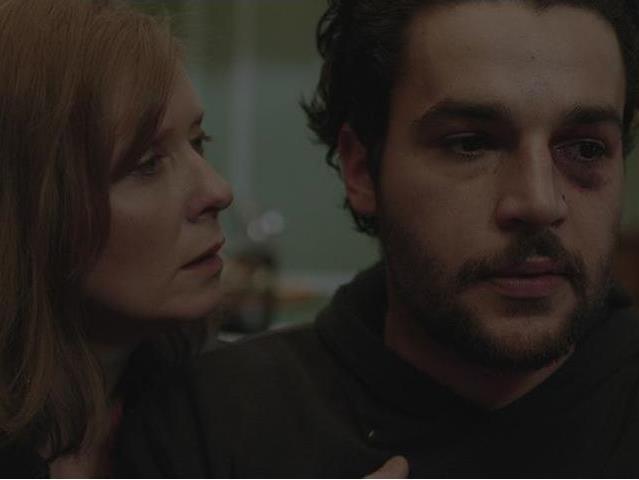

In James White, the eyes have it. In trying to express the state of the titular character (Christopher Abbott, A Most Violent Year), the film’s frames rest tightly and closely upon his face, with first-time feature writer/director Josh Mond staring into a tortured soul in freefall. When the movie opens, James’ look is wired and hazy; when it closes, he’s solemn and weary but clear. Both are expressions of different shades of grieving — and of a gradual understanding that develops over the course of his painful experiences.

James drinks and brawls with his buddy Nick (Scott Mescudi, Entourage), lives on his mother, Gail’s (Cynthia Nixon, Rampart), couch, and seems to wander throughout the world with few aims and responsibilities. A typical twentysomething slacker in a state of arrested development is what he appears to be; however his existence is shaded by mourning: both actual and pre-emptive. The death of his estranged father sparks his first boozy countenance, but it’s the reoccurrence of Gail’s terminal illness that casts a bigger shadow over his days. Playing caregiver comes naturally, albeit erratically; coping with his own fragility doesn’t.

Favouring warts-and-all realism blasted onto the screen with impressionistic vigour, James White is not made for easy consumption. From a storyline that could’ve sprung from a thousand indie films, both a disarming character study and an incisive examination of the impact of loss blossoms. Mond looms and zooms in to focus not on the beats of the tragedies his protagonist is undergoing, as well worn as they prove, but the chaos that engulfs James, leaving him drowning his sorrows in one moment, tending gently to Gail in another, and still self-sabotaging his future in between. The filmmaker eschews the typical trappings that pairing an adult coming-of-age tale and a cancer weepie should bring in favour for restlessness, authenticity and intimacy.

Indeed, in that well-handled match he finds others, as rendered organically and subtly, rather than in a winking way. The constant movement of cinematographer Mátyás Erdély’s (Son of Saul) handheld camera is evident from the outset, yet it so perfectly encompasses the messiness that seethes within the film that it too eclipses any generic connotations. Imparting careening sound to complement the free-flowing vision, Mescudi does double duty providing the film’s music, which cycles from throbbing to tender.

Of course, perhaps the best fit comes from the cast enlisted to enliven the stripped-back material. Every scene in James White gives Abbott a moment to essay his range, while never feeling like an acting exercise — and though he steals the show with his varying shades of the character’s explosively down-but-not-quite-out spirit, he’s also in fine company. Nixon segues from lovingly concerned to physically and emotionally delicate with moving precision, with a shared scene of sweet respite the feature’s standout. Ron Livingston (The End of the Tour) is briefly but effectively used as a reminder of James’ socially unacceptable and unemployable state, and although Mescudi and Makenzie Leigh (TV’s Gotham) help symbolise the protagonist at his most wayward, they play their parts with quiet balance.

What shines through in each of their textured performances and sparkles in their eyes is love at its most raw, sprawling, haunting and human, embodying the bonds that define identities — and the breaks that do as well. In fact, without such clear affection, and without allowing it to roam to extremes, the film’s experiential treatise on grief would’ve lacked its impact. James White conveys not only the bruising hurt and agony of facing death, but the heartbreaking stakes and devastating toll for both the dying and living.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

James White

Director: Josh Mond

US, 2015, 88 mins

Melbourne International Film Festival

July 30 – August 16

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: