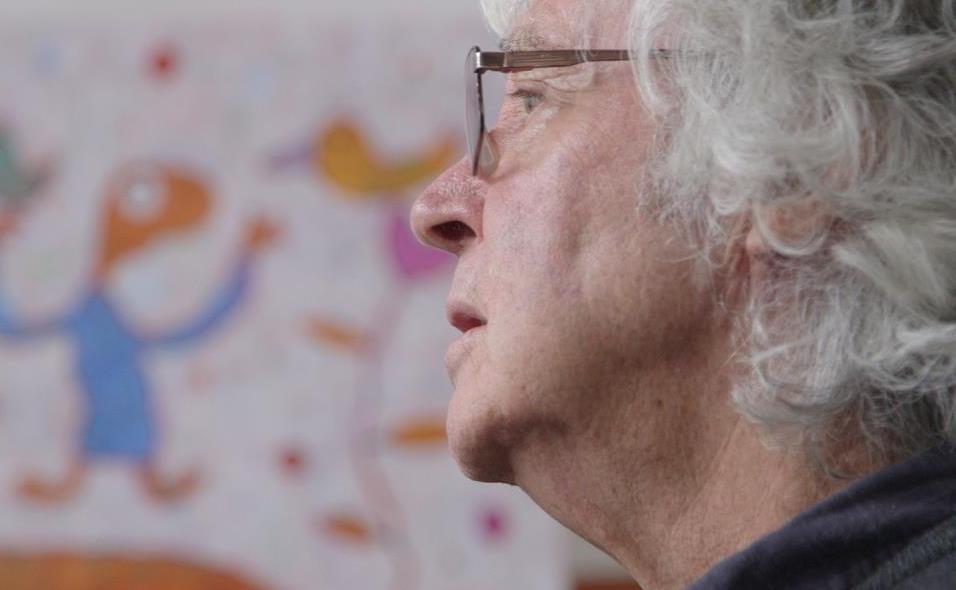

The Leunig Fragments opens how you’d expect from a documentary about Australia’s most successful peddler of cartoon whimsy. Leunig says that “one has to not take [his work] too seriously” and that as a boy he was a “drifting dreamer” as we see him pottering about his cosy kitchen making tea. “I’m not trying to conceal anything,” Australia’s best-known cartoonist says, “I just don’t want to reveal everything.”

It’s a firmly on-message introduction to the much-loved artist and poet, and yet Leunig is right to be concerned; over 90 minutes this documentary goes from a pleasantly warm hagiography to one of the most insightful looks at a major Australian creative figure in years. Calling this film Fragments isn’t just a touch of Leunig-inspired quirkiness; while individual moments state their meaning plainly, director Kasmir Burgess shuffles them to create an at times startlingly revealing look at this “playful provocateur”.

A long-time favourite amongst left leaning Boomers since the 70s, recent cartoons espousing views seemingly running counter to his audience’s beliefs have churned up a fair amount of ire (“He’s much more concerned about telling what he sees as his truth” says a friend). This doesn’t go into detail about Leunig’s beliefs, but it does give air time to his critics – including a comedian who recites a poem titled “I Fucking Hate Michael Leunig”.

The defence here is that he’s always been controversial (though featuring a “hey hey, ho ho, Michael Leunig’s got to go” chant becomes a bit iffy once you realise it’s from a comedy segment by The Chaser), and that strong reactions go hand in hand with his truth-telling. The difference between opposing the Franklin Dam and siding with anti-vaccination campaigners is clear, but remains largely unstated; tellingly, his claim to be an outsider is immediately followed by Phillip Adams saying “some could argue he’s become a total insider… there are dangers in becoming immensely popular”.

Leunig himself largely talks about the world in dreamy, poetic, sensual fashion, whether it’s his somewhat idyllic 50s childhood (recreated through extensive re-enactment) or his current life, largely illustrated by him drifting through various wintery locations. Burgess does an excellent job of capturing Leunig’s tone visually, and while it’s often self-mythologising, the intimacy with which he speaks about the natural world, his clear passion for Aboriginal culture and his fondness for a teacher who encouraged his creative side (in contrast, it’s implied, to his family) is clearly heartfelt.

Utterly estranged from his childhood family – he didn’t know about either parent’s funeral until after it took place, and he doesn’t know where either of them are buried – Leunig’s first wife is mentioned only in an archival news report (that also stresses he fiercely guards his privacy) while his second leaves him after 26 years during filming. Only one of his four children is willing to appear in the documentary, and does so largely to speak about how his father is an aloof, distant figure; “Michael lives down the end of the street, but I wouldn’t go knock on his door,” he says.

Gradually, a more rounded picture emerges. Midway through the film director Burgess is told by Adams that Leunig has a voodoo doll of him; Leunig comes out of a commercial radio interview saying, “I don’t criticise [the interviewer]… he probably has a wretched life, he goes home and loathes himself for being a fraud.” For ten months Leunig vanishes from the film entirely; Burgess in a wig becomes a stand-in for his subject, and when Leunig returns the film becomes largely focused on the looming spectre of death.

A brief coda aside, the film begins and ends with Leunig at the Sydney Opera House, where he appears on stage drawing live, accompanied by an orchestra and singer. It’s a celebration of his celebrity, a crowd present to applaud what is usually a private act of creation. But the performance rings hollow, a gaudy diversion from the increasingly sombre tone of Leunig’s personal musings.

Towards the end of this documentary a friend says Leunig draws from a well of youth – he’s a Peter Pan figure, a boy who never grew up. As a portrait of a seventy year-old who remains a child, The Leunig Fragments is a quietly devastating classic.

|

4 stars

|

★★★★

|

The Leunig Fragments

Director: Kasmir Burgess

Producers: Philippa Campey, Mitzi Goldman, Paul Wiegard

Madman Films,

Australia, 2019,

In cinemas February 13th

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: