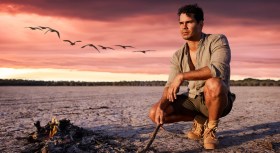

Image: John Kaldor AO, the Hungarian emigre responsible for bringing dozens of public artists to Australia over the last 50 years. Source: Felix Media.

Australians have a pretty benign attitude towards public art… providing it isn’t paid for out of the public purse. We might eye it off suspiciously as hucksterism – as post-Duchamp conceptual art all-too-often is – but we’re pretty chuffed on the rare occasions we find ourselves ahead of the new wave.

The Jeff Koons puppy which took pride of place outside the Bilboa Guggenheim in 1997 hailed from the forecourt of Sydney’s MCA. Sure, it wasn’t the first Koons puppy in the world, but ours was the first to stay upright. And it took an Australian engineer, Douglas Knox, to make it work: 85,000 plants and 100 tonnes of soil, and a modular structure designed to fit into 11 shipping containers. And we flogged it to Spain.

With Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Australia was even further ahead of the zeitgeist. A decade before their international fame – a quarter century before they wrapped the entire Reichstag with polypropylene – the Bulgarian artist and his Parisian partner dumped a million square feet of fabric over a mile and a half of coastline at Little Bay, just south of Sydney. In 1969 Australia, the cartoonists (and This Day Tonight reporter Peter Luck) had a field day. Commentators ranted, nurses from the nearby Prince Henry Hospital sabotaged the roll-out in the dead of night, but the quixotic absurdity of the venture captured the nation’s imagination. Thousands flocked to the coast to “have a sticky.”

What these two public art works have in common is the name John Kaldor. In the last fifty years, the Hungarian emigre has been responsible for bringing dozens of artists to Australia and sending a couple of ours overseas. There have been 34 numbered projects to date. Thanks to Kaldor, some of the most contentious, provocative and divisive artists of the century have made – or shown – work in Sydney. Pioneering queer artists Gilbert and George, the “topless cellist” Charlotte Moorman with Nam June Paik, video artist Bill Viola, minimalist Sol LeWitt, performance artist Marina Abramović… Even if you don’t recognise some of the names – Antoni Miralda, Vanessa Beecroft, Xavier Le Roy, Anri Sala – you will doubtless recognise their iconography and many of their stories.

Samantha Lang’s feature-length documentary – her first – deftly tells the story of the Kaldor Art Projects and Kaldor himself. With a gold mine of talent, archival footage, illustrations and still photographs available to her, Lang marshals her resources brilliantly. She knows when to drill down, what to skip over, and when to indulge the talent.

She shows Australian artist Mike Parr at his cantankerous and menacing best, musing about how we manage ourselves. She lets Asad Raza talk about transparency and the “obesity of understanding” in art and life. She slips in a few intellectual Easter Eggs as if we needed proof that her documentary isn’t mere hagiography. (Agatha Gothe-Snape’s opening comments, in particular, are astonishing in their precision and careful phrasing.)

Kaldor himself, is excellent talent: thoughtful, bright-eyed, shrewd. And that voice – distinctively electric and ever-so-slightly nasal – retains its clipped, careful, Central European accent. Architect (and Kaldor’s sometime deputy) Penelope Seidler, and former Art Gallery of NSW director Daniel Thomas, make telling and engaging contributions.

One of the best and most surprising interviewees is Ellen Waugh, a 95 year-old art teacher who drove from Coogee to Little Bay in 1969 to see if Christo really was despoiling the landscape, as reported. What she found – and captured on Kodak slide film – is that the place had been used as a rubbish dump, even by the supposedly aggrieved local council. Waugh’s undimmed memories of the wrapped coastline, and her undiminished excitement about what the project meant to a maturing nation, are at the heart of the Kaldor narrative.

Ten of the 34 projects are covered in any detail. Apart from the momentous, the controversial and the galvanising, Jonathan Jones’s barrangal dyara (skin and bones) (2016) is one of the most memorable and unusual. Set on the site of the Garden Palace, which housed the Sydney International Exhibition in 1879, and which was destroyed by fire in 1882, Jones marks the floorplan of the building with 15,000 white shields laid out on green grass. It makes a fascinating counterpoint to Wrapped Coast.

While Christo, a refugee from Communism, was violently opposed to agendas in art – any justification, he insisted, was propaganda – Jones’s act of remembrance manages to be equally mythic in scale but easily grasped. It has a simple, human agenda. In this sense, it is the outlier of the projects.

|

4 stars

|

★★★★

|

It All Started With A Stale Sandwich: The Kaldor Projects

Director: Samantha Lang

Cinematographer: Justine Kerrigan

Principal Editor: Elliott Magen

Sound Designer: Liam Egan

Composer: Munro Melano

Production Company: Felix Media

Australia, 2019, 98m

Rated: CTC

Limited theatrical release (Cinema Nova, Carlton, and Ritz Cinema, Randwick) from July 25. Also Luna Palace, Leederville, August 10 and 11.

Q&A screenings with Samantha Lang on July 21 at Nova (at 4pm) and July 23 at Ritz (7pm).

The exhibition Making Art Public: 50 years of Kaldor Public Art Projects is at AGNSW from September 7 to February 16, 2020.

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: