Peter Tregear, The University of Melbourne

This article contains spoilers.

Todd Field’s new, multi-Academy Award nominated feature film Tár is generating considerable commentary – and not a little controversy.

For some, its storyline allows for a timely exploration of intergenerational conflict concerning the value of Western art and artistic ethics. Others see it as a critique of cancel culture.

Still others think it epitomises the problematic representation of women and LGBTQI+ people in a traditionally male-dominated industry.

But I think it also shines a light on some of the social and political dynamics of the world in which it is set: the elite end of the classical music industry.

Power before the fall

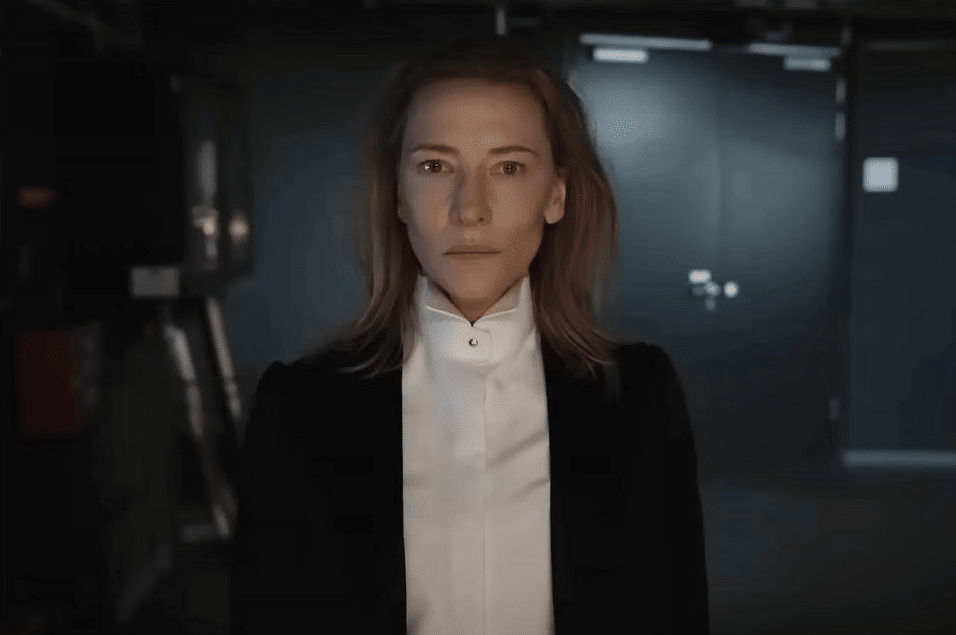

Portraying the professional and psychological downfall of orchestral conductor Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett), the film depicts her as prone to abusive and grooming behaviours. Those behaviours, the film suggests, may have led to the suicide of a young former student (and possible love interest).

Read: Tár review: Cate Blanchett conducts herself ferociously

In interviews, Field has stated he created her character not to explore gender or sexuality, but rather power. The film could have equally been set, he suggests, in ‘a multinational corporation or an architectural firm. Pick your poison’.

But Field’s choice of setting supports his dramatic aim beyond merely providing it with an interesting backdrop.

The globetrotting level of the classical music industry at which Tár works has faced its own #metoo stories.

It is also characterised by especially high numbers of people drawn from private wealth and educational privilege – a situation some argue is only becoming worse.

Late in the film, we discover Tár is from much humbler stock. This informs her character more than we might first realise.

From the outset, the film gives us several clues about her true class identity. Her charitable foundation is named Accordion, after the decidedly non-elite instrument she happens to play. Despite living in a supremely stylish Berlin apartment, she feels more comfortable retreating to the bedsit she has refused to relinquish. She has impostor syndrome about whether all she creates is merely pastiche, if all her creative work is derivative.

Ultimately, we discover she was not born Lydia Tár, rather Linda Tarr. When she briefly encounters her brother, he tellingly remarks ‘you don’t seem to know where the hell you came from, or where you’re going’.

Tár is therefore not a ‘true’ member of the elite level of artists she has fought so hard to join.

Although we initially see her being supported by colleagues who enable aspects of her toxic behaviour or choose to stay silent when they witness it, when things go public, she is unceremoniously dumped.

Ultimately she is not protected by the industry that promoted her, nor does she really know how to protect herself when it turns on her.

This is not the norm. The film names two real-life conductors (James Levine and Charles Dutoit) who also fell from favour owing to similar accusations of predatory sexual behaviour, but their downfalls occurred at the end of their careers, not, as here, at its apex.

Field’s film suggests Tár’s particularly swift and brutal downfall may be in part because she cannot fully access networks of patronage and privilege in the classical music industry.

In this world, personal and institutional power is still intimately tied up with class. Both can be made to serve the interests of wrongdoers and silence their victims.

From Mahler to Monster

There is one other dominating presence complicating the film’s narrative: the music. It is not for nothing Field chose a composition by Gustav Mahler, in particular his Symphony No. 5, for Tár to conduct.

At first glance, here is another artist who might be vulnerable to cancel culture. Mahler had his own history of manipulative behaviour, such as insisting his wife sublimate her own musical career to support his.

Much like Tár herself, the symphony can be characterised as self-aggrandising. As with all his symphonies, it is conceived on a colossal scale and is replete with self-quotations from earlier works.

And yet exposing the personal faults of the conductor and the composer is neither sufficient nor necessary to appreciate the resulting art. As German philosopher Theodor Adorno noted in an essay from 1932, we tend to avoid considering the measure of a conductor’s life off the podium when we watch them on it.

The film reminds us this tendency can come at a significant human cost, and we apply it unequally: depending on not just the identity but also the class background of the conductor themselves.

The film ends with Tár conducting a concert in an unnamed Southeast Asian country. No Mahler is to be found here. Rather, she conducts a program of music from the 2018 action role-playing computer game Monster Hunter: World.

This is not, I think, meant to be some kind of cruel joke (apart from the possible allusion to Tár herself in the title of the game) or a tasteless (and culturally patronising) dig at the expense of non-Western, commercially oriented, orchestral music. But computer game music carries little of the establishment prestige Western classical music does.

The film ultimately leaves it as an open question, but there is a hint that, away from the political machinations of the elite classical music industry, Tár might be able to reconnect with a more authentic – and less destructive – artistic and ethical persona.

Tár is in Australian cinemas now.

Peter Tregear, Principal Fellow and Professor of Music, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.