It was 2am when we saw the bride and groom sitting together on a cold bench outside the hospital emergency department, holding hands. From the front seat of the ambulance we’d watched them approach the after-hours intercom. The triage nurse sounded tired. ‘Take a mask and wait.’

They should’ve been honeymooning in Hawaii with cocktails, not helping each other into surgical masks, fearing a virus. Three days after an American guest at their wedding had coughed all over everyone, his test results for COVID-19 had come back positive. Now others who’d danced with him were sick, including the married couple.

That night, three weeks ago, was the start of it all. Two cases of suspected COVID-19 turned into three the following night, and four a week later. As we responded to cases and learned more about this rapidly escalating pandemic, our nervousness increased. We’d trained for major events and mass casualties, but I always thought of these as train wrecks, air-crashes and earthquakes. My global adventures as a paramedic had exposed me to suicide bombings and tsunamis. Terrible as these events were, I don’t recall feeling the fear I do now. These incidents were somehow tangible. The danger would come and go just as fast, leaving me to my job. Now the enemy was invisible, insidious, creeping like an assassin. As a health worker now, regardless of the protective gear I wear, my risk of dying from COVID-19 is much higher than most.

But I’ve still got a job, and for that I’m grateful. Many of my friends and colleagues in the film industry aren’t so lucky. In less than a month their livelihoods are ruined. I can only imagine how despondent some feel. As a medic, my instinct is to offer hope and reassurance, not least because I’ve seen many people rise from despair to shine again, but also because the dark times in my own life have set the stage for positive transformations.

An example is the making of Jirga, a film I directed in 2016. Australian actor Sam Smith and I flew to Pakistan to make the feature with private finance promised by a wealthy businessman. The money allowed for a huge cast and crew, including an Aussie cinematographer and British production designer. A week before the shoot, under pressure from the Pakistani secret service, the finance was pulled. It was a crushing moment. Passion projects like this involve so much emotional investment that when they fall over it’s like the end of the world. And yet I knew survival and success depended on our ability to adapt. There wasn’t time to lick our wounds. As Charles Darwin said, ‘It is not the strongest species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the ones most responsive to change.’

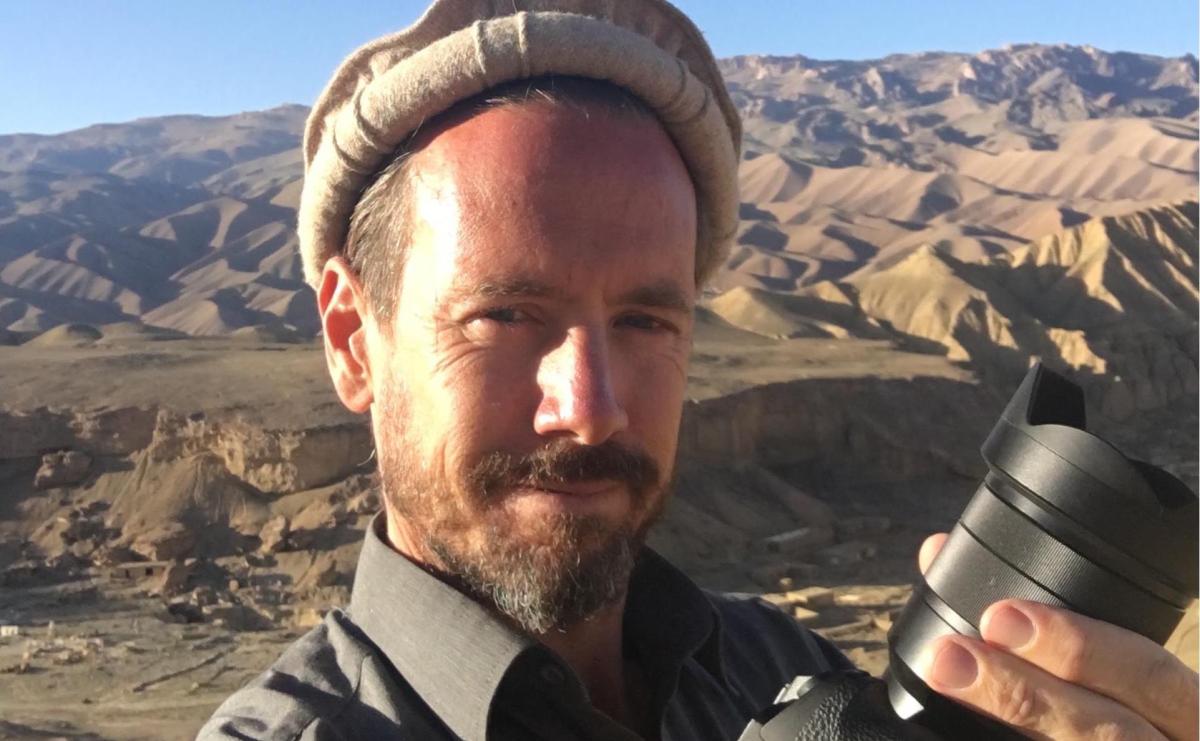

So we bought a camera in a Pakistani shopping mall and tickets to Kabul, planning to chase a few tenuous contacts, care of artist and filmmaker George Gittoes. In Afghanistan, with help from a small band of courageous locals, we shot from the hip on a minuscule budget. Three months later we emerged with enough footage to cut a feature film produced by John Maynard. Jirga played in competition at the Sydney Film Festival, was selected for Toronto, becoming Australia’s entry to the 2019 Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film. It felt like a miracle.

During the shoot I came to realise that having the rug pulled from under us was a blessing. It fuelled our creativity. We created our way out of problems, some of them life-threatening. I learnt that ideas don’t emerge from music or silence or the muse alone, but from danger. Creativity was a vital and invigorating tool for human survival. The more dramatic the challenges in Afghanistan, the more innovative we became. When things went wrong, we saw it as an opportunity. Danger of drone strikes, for example, forced us to change a village location to a cave complex, far more intriguing. At every turn we wove in natural elements that cost us nothing but gave us authenticity. In the wake of disaster, we’d found real treasure. Moreover, I realised that obstacles are part of the deal. How could we expect our protagonist to battle his way through the story, earning his reward of redemption, without us battling too, earning the film? Truth came from this, from being in the trenches with our characters, living the story we were making.

I suppose it’s where we all are now: facing the danger, the obstacles, the fear. We are making enormous personal sacrifices to save humanity. We’re in the ‘hero’s journey’, adapting for survival. And when all this is over, I hope the experience will have somehow transformed us in some positive way. Perhaps our stories will be better for it.