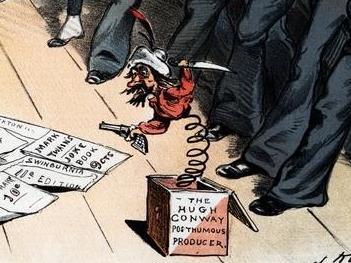

Joseph Ferdinand Kepler drew a cartoon version of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance to protest the pirating of artistic works in the US before the introduction of viable copyright laws. The show was ripped off mercilessly, along the other G&S works. The pirate producer is seen as a jack-in-a-box on a spring.

The illegal online copyright consumption debate continues on its merry way with the release by Turnbull’s Department of Communications of research into the illegal downloading habits of Australian media consumers. The figures cover music, games, television and film.

How big is the piracy problem?

The figures are pretty eye-catching – ‘43% of consumers consumed at least some content illegally’ blares the summary. By direct comparison, only 21% of UK consumers have been hit with the naughty stick. Nearly half Australians have criminal minds, while the British are so much more law-abiding.

How did the report reach this conclusion? Interviewees were asked how much of their streamed or downloaded consumption was legal and 57% said all of it (yay catch-up); 31% admitted to a mixture and 12% claimed all illegally. Add those two last figures together and we have 43% admitting to crime at least some of the time.

BUT, this group is composed of people who are ‘active consumers’ of media on the net. The report also looks at all internet users, and identifies that only 26% of this wider group had consumed at least one item of online content illegally, and 7% had exclusively consumed illegal content. That 26% figure tells us more about the proportion of pirates to law-abiding citizens in the general population, and is comparable to earlier research commissioned by the Intellectual Property Awareness Foundation.

The report itself is calm and lucid but the government’s spin shows that it can easily be pitched in different ways. We too can play that game – it is just as easy, for instance, to say that 74% of Australians with access to the internet never, ever download illegal content, which is an impressive statement of morality. While CNET says that only 20% of pirates would be deterred by warning letters from their Internet Service Providers, we can suggest that one fifth of hard-core IP thieves would be stopped in their tracks.

Behind the research

The Online Copyright Infringement Research Report, is a benchmark study, providing the baseline for further research so we can see how illegal downloading behaviour changes over time.

International research company TNS interviewed 2,630 people over the age of twelve between 25 March and 13 April about their consumption of content over the previous three months. This is a larger survey than IP Awareness has done, as CEO Lori Flekser pointed out, and not directly comparable to earlier research.

It is important to recognise what this survey actually does. It explores the self-image and self-reported behaviour of a selected group, which is not required to make notes over time, or go through lists to note what they have downloaded. It is purely about self- perception.

At the same time, it is scrubbed as far as possible of moral judgement. The report does not at any time mention the term piracy. Instead, it refers to legal and illegal content.

The question of what is meant by illegal and legal is pretty important in a survey about perception. It turns out that 43% of consumers on average are confused about the difference between legal and illegal. For the 55+ cohort that figure is up to 59%.

The badges of legality turn out to be the brand, payment and a statement of legality. This whole area seems to be confused, although the survey does not go into much detail because of that focus on self-perception.

The report is clear that its definition of an illegal source is The Pirate Bay, responsible for 19% of infringements, uTorrent on 28% and the generally mentioned BitTorrent. In other words, piracy = peer to peer and not easy to miss. While it talks about sharing, it does not clearly single out the use of home-burnt DVD or hard or thumb drives, which could be significant, particularly in older groups. It also does not mention Youtube, in which the savvier user could realise that much of the film and television material online is actually stolen even if the exhausted producer has not whacked that particular mole.

The research is based on a UK study, so the intellectual work to create a scientifically useful survey has been done twice over, and users can compare perceptions across two comparable but different societies.

The real spend

Piracy does not exist in isolation – in fact the illegal downloaders are also the users most likely to spend on legal content, with the exception of a small group of pure pirates who never pay for anything.

Average quarterly spend ranged from $12.20 for TV programs to $78.20 for music.

But that spend includes gigs, cinemas and physical copies, and the majority was spent on these real world activities. In other words, people spend more money going to the movies than downloading them, so their online spend is still comparatively minor.

It suggests that 65% of internet users have downloaded or streamed digital content in that last three months; 42% – music, 38% TV, 29% – movies and 15% – eBooks. Given the amount of material on catch-up TV, and the vast use of Youtube, we are left to wonder why 35% of internet users did not even look at a clip or hit iView over that time.

That 15% for eBooks may seem low but it tells us that electronic publishing is biting hard into traditional book sales.

The active users deploy a wide range of services, with the top services being YouTube, iTunes/Apple, Google search and Facebook.

Unsurprisingly Netflix was in the Top Five for movies while ABC iView, TENplay, Plus7 and SBS on Demand all featured in the top 5 for TV programs.

Six legal services for downloading, streaming or sharing content were known by a majority of internet users: YouTube (79%); Foxtel Presto/Play (74%); iTunes/Apple (70%); Amazon (54%); Bigpond (53%); and Netflix (51%).’

What would stop people pirating?

The report has this to say:

A reduction in the cost of legal content was the most commonly cited factor that would encourage people to stop infringing (39% of infringers), closely followed by legal content being more available (38%) and being available as soon as it is released elsewhere (36%).

A number of strategies had a greater likelihood of motivating those consuming a mixture of legal and illegal content than those consuming only illegal content: everything they want being available legally; everything they want being available legally as soon as it is available elsewhere; and availability of a subscription service.

Approximately 2 in 10 stated they would be impacted by the threat of receiving a letter from their ISP: 21% would be encouraged to stop infringing if they received a letter saying their account would be suspended, 17% if the letter indicated their account had been used to infringe and 17% if the letter said their internet speed would be restricted.

Only 1 in 20 infringers (5%) said that nothing would make them stop.

Gradually, the various impediments to legal consumption are being removed, partly because the piracy issues dramatise consumer dissatisfaction. Simultaneous cinema release around the world is common, while the window between cinema and VOD release is decreasing too. Some pundits are predicting the collapse of the whole territory system, to be replaced by world rights.

The government and opposition can take some comfort from the fact that some pirates will be impressed by infringement notices.

Netflix remains confident that the sheer convenience of the smorgasbord subscription service will ultimately kill piracy. However, as Lori Flekser pointed out in an email, ‘After China, the second highest rate of piracy in the world for House of Cards Season 3 came from the US, where Netflix is well established and costs less than $10/month.

Are we a law-abiding community?

Among those who righteously supporting paid content, many are motivated by practicality rather than virtue. They cite are convenience – 53%; speed – 41%; and fear of viruses etc – 32%.

On the other hand, some are also motivated by social awareness and pay to support the industry – 43%, support legal sites – 40% or out of general feelings of morality – 33%.

The stated reasons for infringement are that the content is free – 55%; quick – 45%; try before buy – 35% and that legal content is too expensive – 30%.

But the larger issue for subscription services – of which this is one – remain complex. Lori Flekser at IP Awareness argues that the real objective is the creation of a new morality, in which the community does respect digital creations as owned private property from which makers should expect a return. Here, she wrote, ‘IP Awareness research has consistently shown a decline in the number of Australians who believe that “piracy is theft/stealing from 71% in 2012 to 64% in 2012.’

In the battle for perceptions of crime, the TNA researchers are right to concentrate on people’s subjective descriptions of their own behaviour, because that ultimately drives cultural change. Unfortunately, this is a huge issue, with so many complex factors.

While IP owners say users can’t have their creations for free, that is precisely what we get in a vast range of transactions. We do not directly pay for most television, subscriptions are not directly connected to works, government television is a public good, and we would fight to the death to keep our public libraries.

At least, everyone involved in the piracy debate shows by their rage and defiance that they do value their culture, even if it is supposed to come from some kind of unwearied, all encompassing digital Santa.

——-

The Department of Communications has prepared a graphic summary of the report, while the whole document is also online.

—-