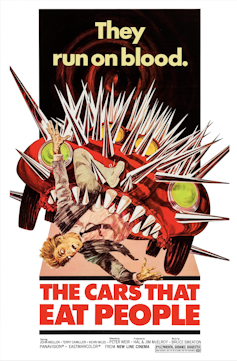

It has been 50 years since the cinema release of Peter Weir’s iconic, offbeat, cult classic The Cars That Ate Paris. The film seared the image of a silver Volkswagen Beetle weaponised with deadly spikes into the national imagination. It also helped shape the tropes of Ozploitation filmmaking within the history of Australian cinema.

Main character Arthur Waldo (Terry Camilleri) and his older brother drive through idyllic countryside, filmed like a tourism commercial. But when a sign diverts them off the highway towards the fictitious town of Paris, it soon becomes clear the place survives on a ‘crash economy’.

Older men in the community orchestrate car crashes on the road into Paris and survivors are taken to a hospital where a psychopathic doctor experiments on them. The townsfolk trade luggage from the cars for food and clothing and wrecks are salvaged by youths who terrorise the community.

The mayor of Paris (John Meillon) pities Arthur and adopts him into his family. Arthur is eventually forced to work as the town’s sole parking inspector, gripped by a phobia of driving, having caused more than one death from behind the wheel.

A uniquely Australian genre

Cars was Australia’s first ‘car crash’ film. These were Ozploitation films, which privileged ‘low’ culture and sensationalist sex, violence, nudity or gore to shock viewers after the R rating was introduced in 1971.

The Mad Max franchise later popularised the car-crash trope to create what has been regarded as a uniquely Australian film genre in the 1970s and 1980s. Movies in this canon included Chain Reaction (1980), Dead End Drive-In (1986) and Road Games (1981).

Both The Cars That Ate Paris and Weir’s next feature – Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), which would catapult him onto the global stage – marked a critical turning point for Australian cinema. They generated increased interest from distributors and film buyers in international markets and established the Australian Gothic style.

Cars is one of our most iconic Australian horror movies, but it is paradoxically a movie most Australians have never seen.

‘No one leaves Paris … no one.’

The slow burn of success

Cars was Weir’s second feature film and a far more polished effort than his first experimental horror. Homesdale (1971) is about the owners of a guesthouse performing hideous social experiments on characters already suffering trauma.

Cars was the first Australian movie to screen at France’s prestigious Cannes Film Festival. It marked a significant achievement for a local movie during the rebirth of the local movie industry, after the production of fiction movies had collapsed during the 1950s.

To market the film, Car’s producers drove the spiked Volkswagen around Cannes’ streets in an ingenious attempt to hype its screening during a packed festival schedule. The film was well received, but as critic David Stratton observed, it proved just too different from anything Australian filmmakers had made before, and indeed to anything being made anywhere.

The film failed to secure a distributor or reach large audiences at home or abroad – though it was released several years later in North America as The Cars That Eat People.

ScreenHub: SXSW Sydney 2024: the Australian films showing at the screen festival

A cult following

A key reason for the movie’s slow reception was also why it became a cult classic: it defies filmic categories. It was originally promoted as a horror movie before being marketed as an art film. This was partly because the movie’s tone shifts jarringly from parody and black comedy to social commentary, before settling on all-out horror.

The story is mostly a dark comment on authority, normality and car culture, which descends into schlock violence in the final act. After the older patriarchy punishes youths for terrorising the streets, a gang of monstrous cars – including the iconic porcupine VW beetle – idle on a darkened hill to the sound of animal noises. The killer cars attack the town, leading to murder, mayhem and a violent battle.

Authur, drawn into the fight, kills one of the youths by repeatedly reversing over him. But rather than express shock or regret, he delights at being cured of his phobia. Arthur drives out of town joyously as survivors of the carnage flee the burning town.

ScreenHub: Return to Paradise, ABC review: a cosy crime cracker in Dolphin Cove

Some things don’t change

The movie’s longevity comes from how it tackles social issues at the heart of the national character. Onscreen we see a dark critique of our obsession with cars and the ‘hoon culture’ that results in tragic speeding or drink-driving-related deaths every year.

The movie also examines tensions between generations. The older, conservative generation arranges car crashes before hypocritically attending church services and preaching justice. The younger hoons bristle at being controlled in a town where they see no future.

One of the movie’s lasting thematic contributions to Ozploitation film is Weir’s depiction of the economic fragility and inopportunity of rural economies that lead to absurdly immoral activities.

More recently, the 2010 film The Clinic adapted this premise by portraying the small town of Montgomery as reliant on an illegal international adoption ring. Townsfolk steal babies and force their mothers to fight to the death in an abandoned abattoir while affluent foreign couples watch on monitors to determine which baby they will adopt.

The Clinic is a bleak, absurd example. But it shows how The Cars That Ate Paris continues to influence Australian cinema in profound and surprising ways.

Mark David Ryan, Professor, Film, Screen, Animation, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.