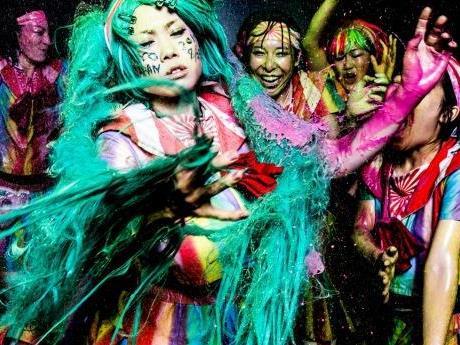

Image via OzAsia Festival

Over the past decade we have seen increasing cultural engagement with Asia. When OzAsia Festival it emerged in 2007 there was no large scale annual arts festival dedicated to showcasing Asian artists on Australian stages and limited Asian engagement across the sector.

Now there is OzAsia Festival and increasing engagement with Asia, as well as Africa and Latin America, through the major performing arts companies and festivals. However, to date compared to Europe and North America it has been in fits and starts.

I have been Festival Director with OzAsia Festival for a year now, and it is timely to reflect on the discussions I have had concerning cultural relations with Asia. From these it is clear there is a need to go beyond justifying artistic programs under diplomatic headings such as ‘soft diplomacy’ ‘people to people relations’ and ‘cultural brokering’.

Australia’s cultural understanding of Asia in the 21st century has been written outside the arts sector. Paul Keating was an early draftsman and there have been others since in fields of politics, industry, trade and education. The arts sector has been slow to the call and therefore has needed to fit into a language of engagement crafted largely by government and business. But the role of the arts is to be ahead of society, to look at the major cultural shifts and explore them in a way that helps us understand our place now and in the future. The benefit of arts-led visioning is that the arts don’t dictate policy but rather open up a series of questions and counter-points that the audience are responsible for collectively decoding.

Arts engagement with Asia often takes place within a government-led framework. The upcoming tour of The Australian Ballet to China, for example, has been tagged in the following way by the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Julie Bishop: ‘Cultural diplomacy is an important and effective way to develop broader relationships between nations. I’m delighted that The Australian Ballet tour will facilitate this with deeper diplomatic, commercial and cultural alliances between China and Australia.’

Is Swan Lake really a great representation of Australian art? What does the decision to tour Swan Lake and Cinderella to China say about us as a nation?

There will undoubtedly be some excellent government to government as well as vital business and trade opportunities to come from taking these shows to China. But the arts per se are not the primary focus in the above quote. Furthermore, there is no way a company such as Australian Ballet can develop a sustainable presence in China at current funding levels without reducing its performance commitments in Australia – meaning that this tour, and future tours, lie at the discretion of the Australian government and for government-related purposes.

Why did the Australian arts sector miss the boat in terms of leading (not following) Australia’s understanding of Asia in the 21st century? A few key points can be highlighted. Firstly, of the 28 major performing arts companies, not one has a current focus on Asia, Africa or Latin America. Australia’s arts sector is still largely based on European models and influences and is thus un-prepared for engagement with contemporary Asia. The major international arts festivals are likewise modeled on European arts festivals and while they take a world-view in programming, the founding principals and dominant content come from Europe and North America. Secondly, looking outside of Australia, a priority for a number of Asian countries is to promote their heritage culture to global audiences rather than showcase contemporary work. This has made it difficult for contemporary Asian artists to develop international profiles with home government support.

The 21st century shift towards Asia has happened quickly. Engagement with Asia is different from that with western nations and our cultural leaders are overwhelmingly educated in European business models (myself included). Leaders running major organizations have their time and energy taken up by demanding annual seasons and festival programs, most of which, again, reflect a European cultural sensibility. The small to medium sector is more fluid and leaders from this sector can self-educate more quickly, but the reality is this sector does not attract the same size of audience and will take longer to develop its cultural influence.

So where to from here? The Australian arts sector must continue to reposition itself at all levels to ensure there is fluid artistic dialogue around contemporary arts in Australia and Asia. This has in fact been happening and there are good examples at the upcoming Darwin Festival, Victorian Arts Centre’s Supersense and Performance 4a. There is also a new generation of artistic leaders such as Kyle Page at DanceNorth and Dave Sleswick at Motherboard Productions brokering collaborations that are not just about broad engagement with Asia but get back to the very essence of artistic exploration: about exploring who we are as a nation, where are we going, and cultivating new cross-cultural artistic forms.

Meanwhile, the OzAsia Festival provides a unique platform to contextualize contemporary Asia to Australian audiences. The program stands at a remove from government cultural diplomacy (even though it is the recipient of government support) and contains the voices of young artists with something to say about their place in the world. Miss Revolutionary Idol Berserker from Japan is a wild rejection of both Japanese stereotypes and post-WWII American influences. The Streets by Teater Garasi is a dance-theatre work that touches on the anxieties of a new democracy in Indonesia. Amber by Meng Jinghui looks at young people creating their own social rules at a time of drastic generational change in China.

There will be talks and discussions around cultural diplomacy at OzAsia Festival. We will even invite key politicians to speak publicly. And I’m thrilled that DFAT’s Australia-Indonesia Institute will hold their next board meeting in Adelaide to coincide with OzAsia Festival. However, these events have all been arranged in response to OzAsia Festival’s artistic program, not the other way around.

The arts sector must engage with Asia and other parts of the world on cultural terms. It must take ownership of emergent artistic relationships and build a language of cultural exchange outside of government dialogue – a language based around artistic inquiry, curiosity, shared interests, questions and desire to find new forms of expression through artistic practice.