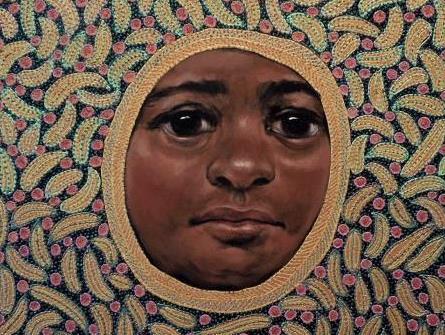

Julie Dowling, Djaa Wara (Poor speaker), Image via Harvison

As I was swept along last month in the sea of humanity that flowed around The Giants I began thinking about the importance of story telling in giving a place its identity. For me one of the most impressive parts of the Giants’ story happened on the Saturday evening with the Noongar elders welcoming the Giants to Wadjuk country. The very large crowd stood patiently and respectfully as the ceremony unfolded. Then it crossed my mind that perhaps the equivalent of the cultural narrative ‘penny’ was beginning to drop, that perhaps there was a greater understanding of the rich and unbroken culture lying underneath the more recent European heritage.

Coincidentally I had recently read David Whish-Wilson’s book Perth, which made me think more deeply about the city and the story that sits behind its transition from the original meeting and hunting grounds of the Noongar nation into the place it is today. David divided the book into four sections following the geography of the place – River, Plain, Coast and Light – thus allowing him to drift through the city and its history in a seemingly effortless way.

Yet this cultural narrative is not readily on show for visitors to understand. Certainly it would be true to say that we have continued to struggle for many years to overcome the difference between how an ancient culture views the land and how the land is viewed through the prism of a European heritage. As a result the two cultural strands rarely intertwine with confidence. That is our great loss, I believe.

Perth has continually welcomed new residents, myself included, over the many years of growth yet there is no unifying framework to explain our history. Yes, some people have gone to great lengths to conserve parts of the mainly post-colonial records.

But do you get any real sense of place as you move through the streets of Perth? How is the multi-layered story behind the growth of Perth laid out for all to understand?

The Metropolitan Development Authority, one of the two main players in the place-making of the central city area, is charged with developing certain locations such as Elizabeth Quay, Perth City Link and Riverside in East Perth. It appears from the plans that a great deal of effort will go into making the new connect meaningfully with the past in those spaces.

In Whish Wilson’s book he writes about Fanny Balbuk, a feisty Noongar woman who lived from 1840 to 1907 and refused to let the European place-making of the Swan River colonists interfere with her traditional pathways. She staunchly maintained the pre-colonial ways by marching through the private gardens and houses of central Perth as if they didn’t exist. I hope that we will see some reference to grass roots stories like this in the pedestrian focused Yagan Square.

The other key player, the City of Perth, has yet to formulate a cultural plan for the central city areas within its control. This differing approach between two tiers of government will no doubt result in missed opportunities that a joined up plan could deliver.

It is worth noting that both Melbourne and Sydney have released cultural strategies to enhance their cities. These strategies embrace the past but look at how the present and future generations of artists can make a unique contribution to the city’s sense of place.

That is why it so critical for all tiers of government to encourage the creative forces of today. It is the artists who will provide the new stories for future generations of residents and visitors to understand why Perth is such a special place.

At the end of this month the Chamber of Arts and Culture WA will be releasing a report into local government’s significant support of arts and cultural activities in Western Australia. One finding stands out; only 18 of the 140 local government authorities have developed a cultural plan that gives a framework to this support.