The Australian film High Ground, set mostly at a mission in Arnhem Land in the 1930s, blends stories (and languages) from Indigenous Nations across the region.

It is a fictionalised story, inspired, says director Stephen Maxwell Johnson, by ‘true history’. At times, the film resembles a shoot-em-up Western. But it gets a lot right.

High Ground was written by Chris Anastassiades and co-produced by Witiyana Marika, (a founding member of Yothu Yindi), who appears in a supporting role as Grandfather Dharrpa and was the film’s senior cultural advisor. It tells of a police massacre of Aboriginal people and the repercussions that follow.

Massacres at the hands of police and settlers were tragically common through northern Australia. The opening scene, depicting a massacre beside a waterhole in 1919, echoes the 1911 Gan Gan Massacre in which mounted police killed more than 30 Yolngu people in a ‘punishment expedition’.

The mission

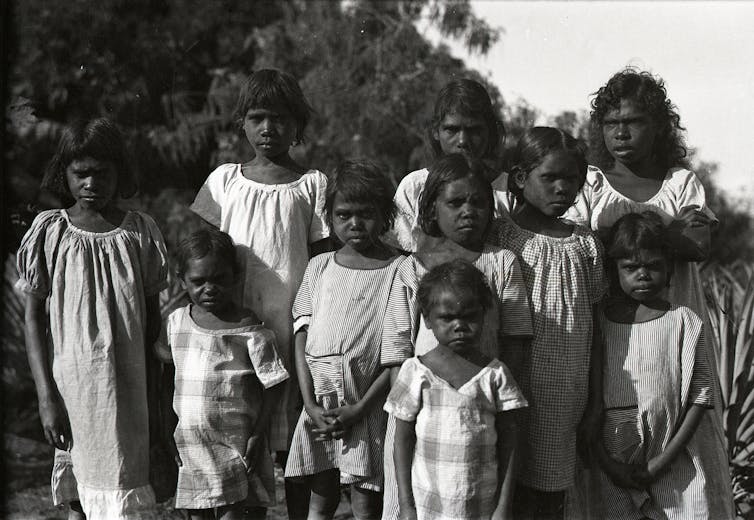

In the film, a young boy, Gutjuk, who survives the massacre of his family, is taken to a mission. The Roper River Mission (now Ngukurr), established in 1908 and run by the Church Missionary Society, really did take in Aboriginal children who had either lost kin, or been forcibly removed from their families.

By the 1920s, there were so many children at Roper River that the society established a new mission just for them on Groote Eylandt. Another mission opened at Oenpelli (now Gunbalanya) in 1925, the subject of our recent book.

Parts of High Ground were shot in the vicinity of Oenpelli, which likely inspired the mission in the film.

The real station

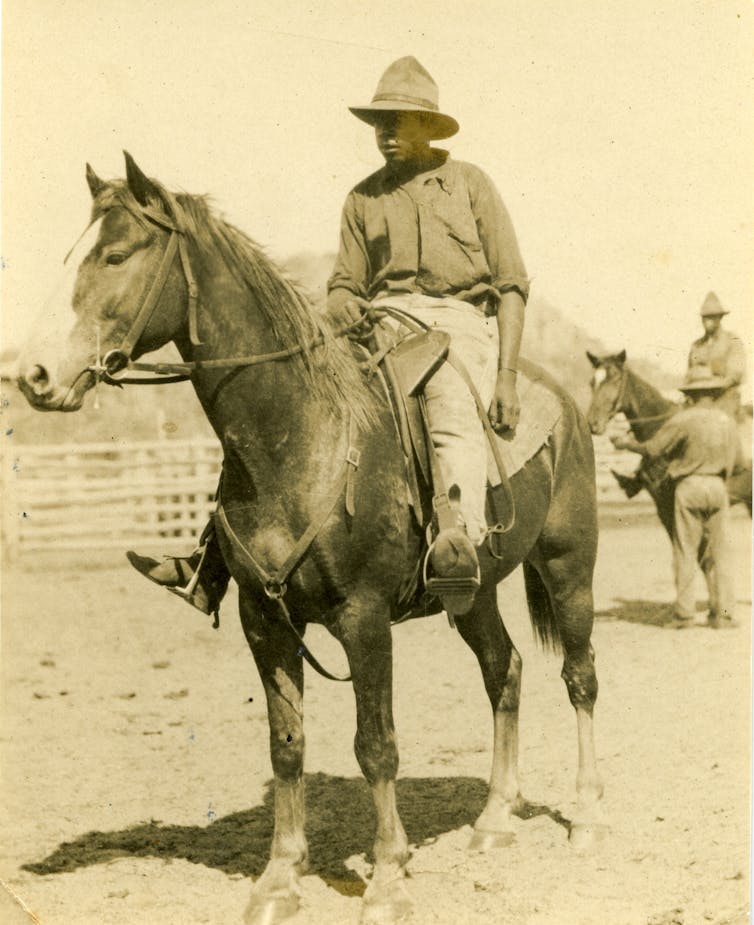

Before it was a mission, Oenpelli was a cattle station and buffalo shooters’ camp run by a man named Paddy Cahill. In the film, a young woman, Gulwirri, who fights to defend her people, has worked as a ‘house girl’ on a station and speaks of the violence she experienced.

Cahill had a reputation for brutality. He wrote of chaining Aboriginal people by the neck. The community remembers how he used to shoot people’s dogs, and his son was known to give workers a ‘hiding’. There are rumours, too, that Paddy was involved in a massacre.

Provoked by his behaviour, traditional owners instigated a plot to take out Cahill and his household. In 1917, strychnine was mixed into the family’s butter, killing their dog, and making Paddy’s wife Maria and two Aboriginal housemaids, Marealmark and Topsy seriously ill. Punishment for those Cahill suspected to be responsible was swift and violent.

In High Ground, the police officers’ earlier experience as soldiers fuels their bloody tactics. After Cahill left Oenpelli in 1922, caretaker Don Campbell managed the station until missionaries arrived. Campbell, too, was a returned serviceman, described as violent. Incoming missionary, Rev Alf Dyer wrote:

There are plenty [of Aboriginal people] about. Mr. Campbell said he had about 300 last Christmas. His policy has been to hunt them, because of the cattle killing; as you read between the lines you will see plenty of problems for the Superintendent of Oenpelli — we will have an uphill fight.

The real missionaries

In High Ground, the mission is run by a young brother and sister team. The latter, Claire, speaks the local language.

The original missionaries at Oenpelli were an older, socially awkward couple with prior experience: Alf and Mary Dyer.

Some have questioned whether a missionary woman would have learned language in the 1930s. But the character of Claire resembles the real figure of Nell Harris, who arrived at Oenpelli in 1933, aged 29.

Read: Film Review: High Ground delivers its own reckoning

Thanks to her Aboriginal teachers, Harris quickly began learning Kunwinkju and, together with local women Hannah Mangiru and Rachel Maralngurra, translated the Gospel of Mark.

The real Gutjuk

In the film, Gutjuk (played as an adult by Jacob Junior Nayinggul), grows up at the mission. He uses this affiliation to work for the interests of his kin in defending themselves against the police, who come looking for his uncle, Baywara, a warrior and survivor of the 1919 massacre.

This reminds us of a real historical figure, Narlim. Narlim was eldest son of senior traditional owner of the land at Oenpelli — Nipper Marakarra. Narlim was born in 1909, making him around the same age as the fictional Gutjuk.

Narlim grew up at the mission because, after working for Cahill, Nipper saw strategic value in an alliance with missionaries. He also wanted his children to learn to read and speak English. This alliance was a way to ensure continued life on Country and to maintain sovereignty as traditional owners.

But, as in the film, missionary cooperation with police was disastrous for Narlim. When a policeman visited in the late 1930s, he found Narlim had an infectious disease. The policeman handcuffed Narlim, intending to chain him with a group of others to be sent to Darwin.

The missionaries said the chains were unnecessary as Narlim ‘would behave’, but they did not save him. Narlim was exiled from the mission and his country under police escort, baby daughter on one shoulder and spears on the other, never to return.

His daughter, Peggy eventually came home and became a strong community leader.

The real ‘punishment’ and ‘peace’ expeditions

In 1932, Yolngu warriors killed a party of Japanese pearlers trespassing on their country. Constable Albert McColl was sent in; he too was speared. So police proposed a ‘punishment expedition’, not unlike those depicted in High Ground.

After a humanitarian outcry, the society proposed a ‘peace expedition’ instead. The expedition went unarmed to the Yolngu warriors. Unlike events depicted in the film, three were convinced to come to Darwin for trial. The men were found guilty but eventually released. Yet one, Dhakiyarr, disappeared after his release. The open secret in Darwin was that Dhakiyarr was drowned in the harbour in an extra-judicial police killing.

The film gets right the ambiguous missionary relationship to violence. Missions were meant to be a refuge from inter-tribal and settler violence. Missionaries understood their humanitarian and evangelistic work as seeking to atone for the bloodshed of colonisation.

But they also relied upon and enabled the ongoing violence of settler authorities. As ‘Aboriginal Protectors’ missionaries functioned as local sheriffs and carried guns. Missionaries would send Aboriginal people for trial in Darwin, or else implement their own punishments.

As portrayed in the film, missionaries joined expeditions to capture supposed lawbreakers. Alf Dyer, for instance, led the so-called ‘peace expedition’ to convince Yolngu men to face trial in white courts.

The historical record

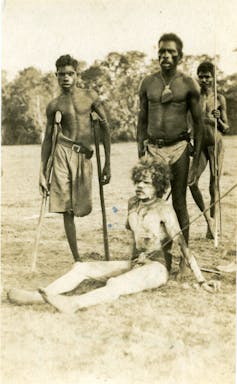

High Ground also shows how self-conscious white authorities were creating a historical record.

The chief of police, played by Jack Thompson, seems to be always directing a photographer to take portraits. These images were good for fund raising, for impressing officials. They do not reflect the full story of the community. But they do give us a glimpse of the complex relationships in Arnhem Land in the 1930s.

High Ground, of course, is a highly dramatised piece of art. But, as the filmmakers have said, it’s closer to uncomfortable historical truths than we might expect. By showcasing such stories, the film will hopefully encourage broader reflection on Australia’s violent history, and its enduring legacies.

![]()

Laura Rademaker, Postdoctoral Research Associate, Research Centre for Deep History, Australian National University; Julie Narndal Gumurdul, Senior Traditional Owner, Gunbalanya community, Western Arnhem Land, Indigenous Knowledge, and Sally K. May, Senior Research Fellow, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.