This article contains spoilers for the film EO.

EO, veteran polish director Jerzy Skolimowski’s latest film, is about a former circus donkey and his many adventures a he is passed from owner to owner. It’s boldly experimental, and more importantly will make you cry until you’ve got no tears left. EO asks us to look at a farm animal and put ourselves in his place, and by doing so recognise the cruelty we as human are capable of.

How does EO achieve this?

The official logline doesn’t tell us much about the plot, but it positions us perfectly to relate to its main character: ‘EO, a gray donkey with melancholy eyes, encounters good and bad on his journey through life, experiences joy and pain, and endures the Wheel of Fortune.’

I’ve bolded the phrase ‘melancholy eyes’, because in creating empathy on film, the eyes are key.

‘We use others’ eyes – whether they’re widened or narrowed – to infer emotional states, and the inferences we make align with the optical function of those expressions’, according to research published in 2017 in Psychological Science. An example is if we see eye being narrowed in order to scrutinise, that conveys scrutiny to the perceiver. Likewise for eyes widening in fear or scrunching up in joy. When the camera moves in on EO’s big brown eyes as he witnesses a wolf being shot, we understand he is feeling afraid.

An additional study conducted by the same research group found that ‘the eyes provide equally strong emotional signals when they’re embedded in the context of a whole face, even when the features in the lower face don’t indicate the same expression as the eyes do’. Since EO’s mouth can’t do a whole lot expression-wise, the camera totally relies on his eyes, and thanks to our emotion-motivated brains, this works wonders.

Read: The Banshees of Inisherin: history hangs heavy in Irish Oscar hopeful

Silence is golden

You’ll surely be familiar with the term anthropomorphism – which means to assign human characteristics to an animal (think about all the talking, front-eyed dogs and cats in Disney films, or just Donkey from Shrek). But EO avoids this technique.

Throughout the film, we are very much aware that EO is an animal, and all the traps that come with that – the inability to speak, needing four legs to walk and not getting very far – are part of why we feel so strongly for him. Placing ourselves in his shoes, or hooves rather, means we have to think about what life would be like as a donkey, and not what it would be like if EO were human.

This directorial choice means that EO is mostly dialogue-free. With the clatter of human speech reduced to only a few lines, we have time to really appreciate what the visuals are telling us instead. We wonder what EO is thinking a he takes a moment to pause on a bridge overlooking a waterfall, or as he gazes at a beautiful white horse as it prances around its arena.

Read: The Last Unicorn: revisiting the cerebral folk-horror at 40

Showing vs not showing

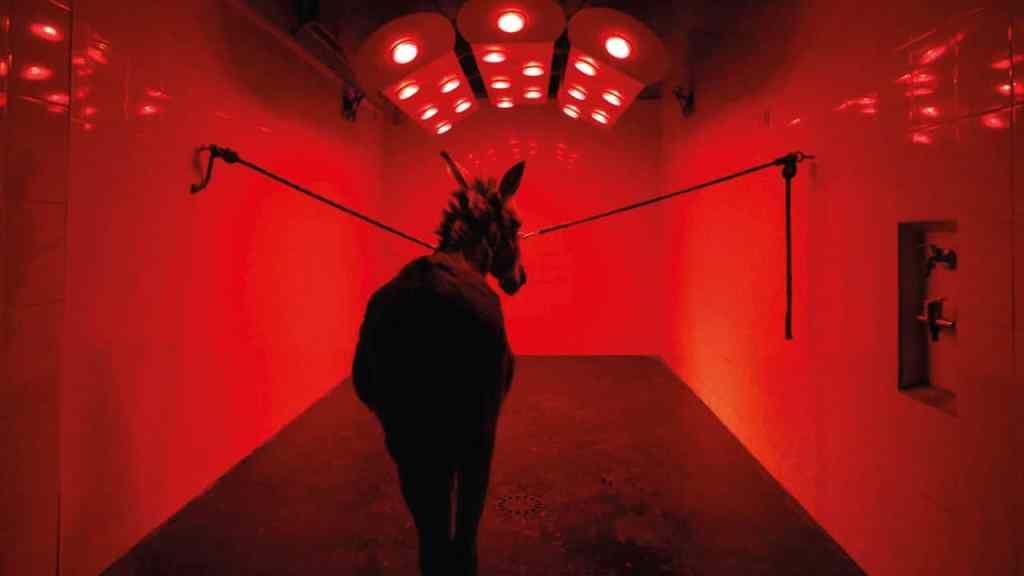

There is a shocking moment [SPOILERS AHEAD] when a group of drunk football supporters beat up EO with bats, and it’s filmed from the donkey’s perspective. Despite never seeing the hits land on his flesh, we feel every strike as if we were the victims.

When the offenders are done, we do not see the result of their carnage – instead the donkey is replaced by a Boston Dynamics-style robot that struggles to get up, and then stumbles toward a potential saviour. It’s an incredible artistic choice that keeps our empathy while ensuring not to exploit or glorify violence towards an animal.

This scene garnered a huge emotional reaction from me – sobbing and pleading ‘no!’ at the screen – despite removing all living creatures from the frame. I think it’s because we know the robot represents the injured donkey, and by not showing us his injuries we are made to assume they are so bad that we are being spared the distress of seeing them. It’s incredibly powerful stuff, and it only lasts a minute or so.

Farming emotions

Recent films like Gunda and Okja (one about a real farm pig and the other about a fictional super-pig that’s bred for meat) work in a similar way to EO: one, the title is the animal subject’s name, so there is no doubt about who is our protagonist, and two, the camera favours their perspective in many key moments that force us to wonder what it is like inside that animal’s mind.

Both Okja and Gunda illicited big emotional responses from me and my partner as we watched them – the kind where you wipe your snot away afterwards and wonder aloud: ‘why do I care so much about a pig??’.

In an interview for the Berlin International Film Festival, the director of Gunda Victor Kossakovsky said this:

‘Many films are made about animals, and normally, they feature people talking about them, explaining them. That takes the attention away from the animals. I didn’t want to patronize or humanize them. Films that show animal slaughter and explain all its gory detail also don’t work. It is propaganda, and people block it out. So, I thought, let’s see what the camera can do on its own.’

When a film invites us into the inner world of another being, whether it be human or not, we usually have little choice but to empathise. Thus, when we witness the inevitable cruelty that befalls the title animals in Gunda, Okja, and EO, we become very emotional – grief-stricken, even. This reaction is perhaps also emphasised due to the fact that, in our day-to-day lives, we don’t think that deeply about farm (and other) animals.

One of the successes of films such as these, and to others of their kind, is that we feel – or even know, for a couple of hours – we really should.

EO is in select cinemas nationwide from April 6