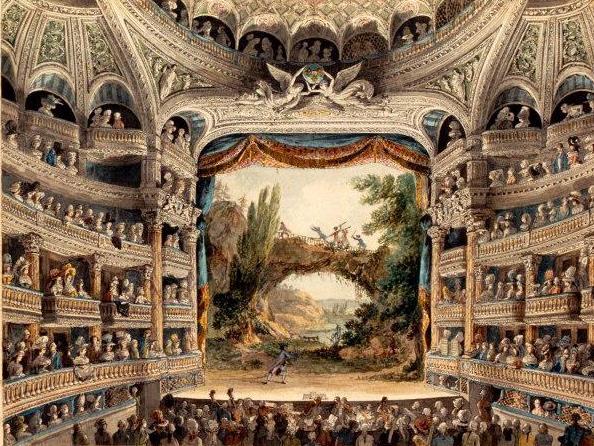

Image via Wikimedia

Malcolm Turnbull wants to be a 21st century leader of a 21st century government with a 21st century frontbench. So how might that translate into a 21st century Australian arts policy?

First, let’s take a look at how we got here.

Arts policy began in the depths of World War II Britain with the formation of the Committee for the Encouragement for Music and the Arts, the forerunner of all modern Arts Councils, the first chair of which was the arts patron and economist John Maynard Keynes.

Modern arts policy has never really departed much from this initial charter of Keynesian-type tax-and-transfer justifications and centralized elite representation.

This can be observed plainly in the International Federation of Arts Councils and Cultural Agencies, which, for all its new-management speak of “good practice guides”, is still an industry lobby devoted to spending taxpayer money on its clients. This is not the place to look for 21st century solutions.

To bring arts policy into the 21st century, we need to update and correct the basic economic flaws that were baked into the mid-20th century model.

We must recognise that: (1) the once plausible market failure justification is no longer, (2) producer-focused industry protection has systematically failed, and (3) that an elite, protectionist focus is unsustainable.

End of Market Failure

A standard justification for government spending through the 20th century was market failure. Market failure occurs when market incentives (i.e. prices) are insufficient to induce the “correct” level of private consumption and investment evaluated from a social welfare perspective.

The solution to this alleged failure is for government to step in. Arts and culture was widely argued to experience market failure because of what economists call uncompensated positive externalities and endogenous preferences.

Simply put, uncompensated positive externalities means the private production and consumption of art benefits the broader community, who can experience that benefit without paying for it. Endogenous preferences refers to the age old belief young people don’t really know what is good for them and will tend to choose the “wrong” culture.

Former minister for the arts, George Brandis, introduced funding policies that prioritised “heritage arts” such as opera and classical music. It’s the same type of argument parents make about broccoli. The upshot was a raft of direct subsidies to elite cultural producers.

But in the 21st century, are these market failures still there? There is a strong case to say no – they have mostly vanished, and as the US arts and cultural economist Tyler Cowen argues, for reasons largely associated with market-driven economic growth and technological change.

New information technologies of search, coordination and payments, and digital technologies of production, storage and dissemination – think crowdfunding platforms such as Kickstarter, Pozible, Indiegogo and GoFundMe – have phenomenally lowered the costs to both finding niche audiences and producing content for them.

Technological change has shifted the margin of the range and scope of artistic production that is now profitable. The market no longer fails.

The classic funding model in the arts is patronage, which was taken over by government mid-20th century, in what appeared at the time to be the crisis of capitalism. But capitalism has well and truly come back, and created vast wealth that can be recycled through effective patronage and philanthropy, whether corporate or private.

It is also far from clear that the arts are a public good, benefiting the general public and deserving public subsidy, but might rather be better understood as an industry designed to primarily benefit its own members.

Consumers not producers

A further great lesson from 20th century economics is that policy should focus on seeking to create benefits for consumers, not for producers.

Producer-focused policy, which was an outgrowth of the economic socialist planning models of the mid-20th century, was standard practice across the economy until relatively recently. In industry after industry, these were the models of subsidy and protection that caused producers to devote great efforts to lobbying agencies and politicians – a wasteful activity that economists call “rent seeking”.

What they didn’t need to do was to devote resources to producing better products, or new technologies, or new business models, or cheaper products. So producers were focused on courting government, not consumers. This turned out to be very bad for consumers.

These economic policies did benefit producers, who could organise to seek these benefits, but invariably harmed consumers, who were not so well represented. They were, in other words, politically but not economically successful.

The same argument applies if we substitute artists for producers, audiences for consumers, and Arts Council Boards for government.

The basic problem with the current 20th century arts funding model is that it remains producer- or artist-centric, rather than focusing on audiences and citizens. This makes it ripe for capture and lobbying.

It almost guarantees that it will only produce what the artists want to produce, because of what benefits them, or what the Arts Councils want them to produce, not what the audiences and the citizens who pay for it all actually want to see.

Creative industries

A major global shift in the policy perception of the arts and culture began in the UK in the late 1990s, with the gradual rebranding from a backward looking cultural heritage model and toward an innovation, design and content focused “creative industries” model. This was lead by the UK Government’s Department of Culture, Media and Sport.

This has manifested in the movement of the arts and culture portfolio from the periphery of strategic politics to ever closer to the central portfolios of innovation and economic growth and development.

The basic idea here is to recognise that a 21st century economy is no longer a mass industrial economy, but one that is increasingly dominated by knowledge intensive services. The arts and culture can thrive in such an economy when it engages and interacts with it. The old protectionist model is a very poor fit here.

A new arts policy approach

So let’s shed the legacy of the 20th century. That means being utterly clear about what that legacy was: it was a producer-centric, subsidy-based model.

A better approach will be one that recognises the new power artists have to appeal directly to their potential audiences for funding. The government no longer needs to create tax-payer-provided havens for the profit of artists and producers.

As an Internet commerce pioneer, Mr Turnbull, of all Prime Ministers, should be aware of this.

We need to shed the old fashioned, crude and wasteful subsidy model, and instead embrace an approach centred on audiences and citizens, and that works with philanthropic benefactors.

Finally, while the branding of the creative industries tends to associated with New Labour (and Labor) policy, it’s a good policy idea. The Coalition government should have no shame in stealing this.

This article was first published on The Conversation.