The figures do not lie. image: Judy Davis in My Brilliant Career, directed by Gillian Armstrong, written by Eleanor Witcombe, produced by Margaret Finke.

Last Friday Screenhub announced the 2017 Australian Directors’ Guild (ADG) Awards nominations with tag lines that new directors are on the rise but the gender statistics are ‘pretty ghastly’.

Read more: Rise of new directors in ADG nominations.

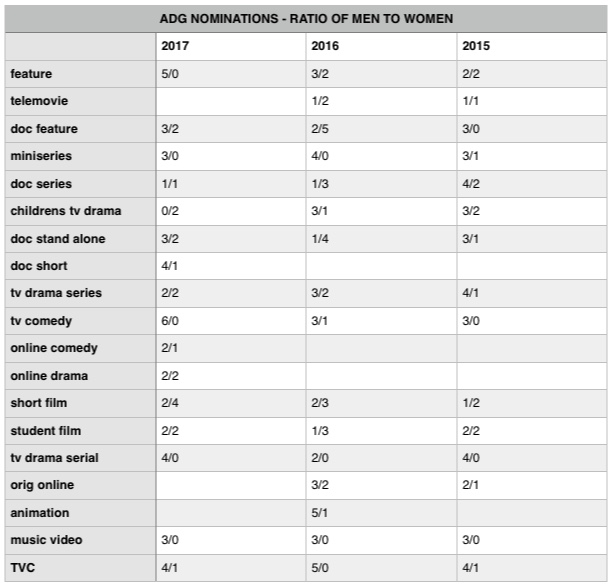

The gender disparities for the last three years are show in this table:

The figures from David Tiley and the ADG offer some transparency – but what do they actually tell us?

1. Gender bias against women and men

One of the interesting revelations in these figures is that there is an indication of gender bias for both genders! (Yes, men as well!)

The category ‘children’s television drama’ is 64% women. This arguably indicates that there is a gender bias that segregates the industry on gender grounds. E.g. an unconscious bias that women would be better with children’s content. Any block to diversity is undesirable. For example, a highly experienced Indigenous director told me he only got called in to direct by a major broadcaster when there were Aboriginal characters or storylines. So understanding and making visible gender bias, and other bias, is an important part of improving equality for all across the industry.

2. Women aren’t funny

I am being provocative, but the fact is that women only got one ADG nomination in three years for ‘TV Comedy’ – and 0% of female directors got a gong in 2017. Does that reveal that women are just not funny and therefore not able to deal with directing comedy? I don’t think so. I think it exposes a gender bias that is visible in the wider industry, one that is preventing women getting that work. As Stayci Taylor wrote in her PhD dissertation, there is a ‘comedy-gender divide which would appear to be an ongoing concern’. As a writer, she observed that at home and abroad, mainstream comedies are male-dominated. Surveying the research, Taylor explained that where hundreds of male driven comedies have been made, during the same time period, only a dozen female-driven films were commissioned. Given women make up half of the audience, they deserve half the laughs – so women need more opportunities in comedy and there is no shortage of funny females. Positive discrimination for women in comedy is needed here.

3. The industry is still segregated

Children’s television and other areas that are heavily weighted to one gender or another illustrate that the industry is still segregated in some places. Identification and redressing imbalances will make more inclusive cultures and enable people in the industry to experience the full ambit of their creativity – and positively drive innovation.

4. Affirmative action is needed

The most recent Screen Australia stats for female directors of feature films in Australia is only 16%. What is worse, in 1992 the antecedent of that same organisation measured it at 18% – so affirmative action is absolutely necessary, and the Gender Matters initiative is both welcome and long overdue.

The Australian Directors’ Guild has massively lifted its game in responding to the dearth of women directors and they have taken up an affirmative action gender agenda. They have a female only internship for women in television commercials, and one for women in television; they’ve establishing an affirmative action subcommittee (whose members include Gillian Armstrong and Megan Simpson Huberman), a female president (Samatha Lang); and they have conducted panels on women in film (such as last year at The Melbourne International Film Festival). So although a long time coming, and directing has been an area with one of the smallest female participation, to its credit the ADG has seriously responded to the issue. In its awards the guild is dealing with the product the industry produces – which right now is leaving women out in many areas.

These figures suggest that so far affirmative action has not made a dint. Therefore, if we really want to sustain change, all parts of the industry have to keep it up and make a long-term commitment since the historical record shows women can slip backwards in terms of numerical representation. Initiatives should be developed where women are not getting a foot in (as the ADG have done with women in commercials).

5. Naming and shaming

To ‘name and shame’ is publically saying ‘that a person, organisation, or business has done something wrong’ (which I am not doing here, just raising a hypothetical). Is there ‘wrong doing’ visible in these nominations? Potentially there could be. For example, there are a few male bastions, such as the category ‘TV drama serial’ – 0 % of women over all of the last three years. And the same could be said of other categories, such as the music video (which also had no female nominations in three years). So the popular drama series should be studied further to see what the gender balance is, and if those who produce it need to raise the bar in terms of female participation.

I am not naming them here – just putting them on notice that this could be coming as it did with the WIFT sausage protest at the 2016 AACTAs. It is better to target those who can are directly responsible (given awards are not film funding mechanisms), and those who make the decisions are likely to be in the firing line. For example, one year the group Guerrilla Girls put out badges at the Sundance Film Festival that named the distributors who didn’t have any female directors on their lists. The campaign was: ‘These Distributors Don’t Know How to Pick Up Women’.

6. Analysis and research

In 2014 the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) did a study of its own records for selecting women directors and for giving them Awards. They found (and published on their website) that there was a direct correlation between the numbers of women selected to the festival, or numbers winning awards, and the gender balance of the panels. They now work very hard to have 50/50 gender balance on those panels. I am not implying this is the case in the ADG Awards, it could just be that the ADG demographic of members are heavily male (given the participation of women directors in Australia is also), but the industry needs to keep an eye on this, and ensure we collect gender and diversity statistics (research).

7. Protocols

On top of research, advocacy for gender equality is needed. UNESCO have a term called ‘gender mainstreaming’. Under that protocol, one always asks if there were women that were overlooked, and any panel is required to ask: have we got women in the mix and if not, why not? It might not mean any change, but the protocol ensures double-checking before locking in the nominations or employment shortlist (and everyone, including women, are susceptible to gender bias and patriarchy).

8. Barriers at the doorway

One of the best performing areas for women also flags a problem. In the short film genre around 66% of nominations are female, and the category of student film is 50% women. The question is, what happens as all these talented women, with all these award nominations, emerge into the industry? Participation is not being sustained. There seems to be some gap between emergence and getting the gig. So clearly, more entry-level initiatives are warranted: mentoring, new filmmaker schemes, networking opportunities, building capacity or skills development for new (female) players to enter the industry (e.g. pitching, negotiating deals).

9. Women are punching above their weight

Women also represent 50% or more of nominations in ‘Documentary Series’, ‘TV Drama Series’, ‘Online Drama’ (on top of ‘short film’, ‘student film’ and ‘Television Drama’ – already mentioned). For some time statistics have shown that women have been making gains in television, and documentary has been a place women have been able to strongly participate (often because they can create their own opportunities and, like men working in documentary, act as writer, producer, director, editor). But ‘the big end of town’, the features, feature documentaries, TV drama serials, the areas with the bigger financial return, still appear to be the domain of men. So statistics that show women’s productions are as financially viable (which they are), are needed to counter perceptions. Some international studies have shown that productions by women in key creative roles perform marginally better financially (e.g. see Sinclair et al’s Scoping Study into the Lack of Women Screenwriters in the UK). And women win a lot more awards than their numerical participation in the industry. As I wrote in the Lumina special issue on women in film and television: ‘women were represented in all competitive categories at the 2015 AACTA Awards (except Best Light Entertainment TV Series); and women won 50 per cent of sole awards, or shared 57 per cent of wins – further evidencing women’s performance above their numerical representation’.

10. Transparency is helpful

Being able to read the statistics for the ADG Awards and to see the ratio of men to women is enormously helpful. Transparency enables contemplation of the issues and forming responses to them. Statistics, information and research form the evidence basis for action, so all guilds, unions and industry should be collecting and interrogating such data.

Lisa French is a Professor and Deputy Dean of RMIT’s School of Media and Communication. Her publications include the book Womenvision: Women and the Moving Image in Australia and the Lumina article ‘Does Gender Matter?’ She is Co-Chair of the UNESCO University Network on Gender, Media and ICTs and is currently writing a book on women directors and the ‘female gaze’.