In 2009, the first Avatar film occupied 588 screens to take $15.35m (adjusted for inflation) over its first weekend. In 2022, Avatar: The Way of Water launched with $16.6m off 1,281 screens, in the biggest campaign since the start of Covid. The two films have made almost the same amount, despite Covid and 13 years of space opera in between.

Earlier this year, Thor: Love and Thunder took $15.76m, while Top Gun: Maverick made $13.8m in its first weekend. These films set the 2022 benchmark for the best openings in Australia.

Elvis made $6.75m in its opening, six months ago. But it went on to make $33.47m while Thor: Love and Thunder has taken $44.33m and Top Gun: Maverick belted out $93.07m.

Nonetheless, Elvis is a major success, in profit, with $422m around the world off a modest budget of $125m, compared to $250m for Top Gun: Maverick. We can call that a fabulous achievement.

In a perfect world, we would call the other results mediocre. Let’s find out if that sad judgement is fair.

How well did the 2022 Australian films do in Australia?

Our first problem is defining a film as Australian. We are taking a very broad brush, reflecting the way in which only three of the seven films in our key list are really domestic.

The next film on our list is Good Luck to You Leo Grande, which is in a class of its own because it was directed by Sophie Hyde with Bryan Mason shooting and editing, off a pre-existing UK project and script. Indeed, the producers would claim it as British or Anglo-American to reflect the financing.

It is here because some central talent is Australian and points to the way that nationality is becoming less and less relevant. It made $1.87m in the UK, $3.25m in Australia, $2.025m in the Netherlands and $1.79m in Germany, a scatter of results across the rest of Europe and nothing from either North America and Asia. The total was $13.7m.

So it did much better here than in the UK, despite the name recognition for the English involvement backed by four nominations in the British Independent Film Awards and no obvious links to Australia.

It is streaming on Hulu in the US, and on Apple TV, Google Play and Prime Video here.

Read: Leo Grande beats box office performance anxiety

Wog Boys Forever made $2.92m here, and is streaming on Paramount+. The first film in the franchise made a total of $20m in 2000, while the second took $6m ten years later, so it has been steadily rejected by audiences and comedic taste. Broad and rough is gone forever.

How to Please a Woman took $2.40m, followed by The Drover’s Wife on $1.19m, Three Thousand Years of Longing with $1.36m, and Falling for Figaro $1.13m, which had an Australian team in producer Judi Levine and director Ben Lewin. Five of these seven films, which came through very different selection processes, have woman leads and female stories. Four of them are fundamentally international

Read: Judi Levine reflects on going global in a filmmaking family

From here we drop to Seriously Red, which has taken $686,00, followed by Little Monsters with $475,000 and The Lost City of Melbourne, taking $309,000 in the tenth slot. Even though it is ultra-local, it is beating environmental classic Franklin with $295,000. The other four are well down, reflecting a general slump in documentary results this year.

As Screen Australia points out: ‘In 2021, feature films under Australian or shared creative control earned $71.5 million or 11.8% of the total Australian box office (including titles that screened in 2021, with a prior year of release). This is up on the previous year, when the share was 5.6%, and above the 10-year average of 4.9%.’

These annual comparisons tell us much less than they seem. The total box office for our domestic and co-production releases in any one year is all over the place because a single mainstream success can drag the figure way, way up and a run of successful lower budget films don’t get the prominence they deserve. This is why the statisticians of screen performance rely on three year rolling averages, which are not yet computed to include this year.

By my count based on the weekly figures, the total for 2022 is $98.076m, which drops to $64.6m when we remove Elvis. Remove Leo Grande, for its lack of Australian finance, and that number goes down to $61.21m. Either way, this is a good total in hard times.

Some comparisons?

Once again, I am concentrating on films that earned more than $1m, because they had some marketing support. These are very strange times, as we all keep telling each other. But seven Australian(ish) films took more than $1m in 2022, which is encouraging and suggests that modestly budgeted film are having some cut-through.

There is a sense of change over the last few years. In 2018 Peter Rabbit made $26.79m, Ladies in Black made $12.14m, Breath made $4.64m, Sweet Country took $2.03m, Swinging Safari made $1.62m, and Gurrumal made an even $1m. That adds up to $48.22m from six films taking over $1m. Again, Peter Rabbit had US studio backing.

In 2019, Ride Like a Girl hustled $11.78m, Top End Wedding did $5.29m, Storm Boy took $4.99m, Palm Beach $4.51m, Hotel Mumbai $3.31m, Danger Close $2.97m, and documentaries The Australian Dream and Mystify: Michael Hutchence both made $1.15m. That’s $35.15m for eight films above our $1m floor.

There is no studio film here – as Covid struck, Elvis was suspended and the US tentpole conveyor belt began to fling films sideways into streaming.

To get down to the nitty-gritty of change requires a lot of detailed work and conversations with defensive people. My gut feeling, after tracking box office for well over a decade, is that box office is much harder to attract, and social media is having less effect while the films are tending to get better in general.

But the film sector is hanging in and doing as well as most other cultures. Conditions are pretty terrible for everyone and the weird sham economics by which we get government to finance private enterprise mechanisms is the same everywhere.

A decade ago, the swivel-eyed critics of the Australian screen sector could say that the Americans did without subsidy, but Hollywood studios read the international system and clambered onto tax subsidies like hungry raccoons. Our taxes help to pay for their films as the US state system learns to mimic the world’s approach to cinematic nationalism.

Nonetheless, the figures are still very modest and our sector is highly subsidised.

What is wrong?

Covid is the obvious culprit, but is not the real villain of the piece. On the arthouse and respectable entertainment circuit, the boomers are getting older and dropping out, hampered by declining energy and increasing fear of infection.

But they were always going to disappear and subsequent generations will not replace them, because they are caught up in a wider range of digital entertainment. Also, we know they are having a harder time financially.

The true beast, dominating the discussion at least since Netflix arrived in 2015, is streaming, which is a clear winner, supercharged by Covid.

On an income level, every other media form has been blown up by the transfer of advertising onto the net. So the death tractors have come at cinema from both sides.

The exhibition sector has carried on for 120 years and fought off every single assault – radio drama, the technical challenges of sound and colour, the battles between studios, the rise of television, nothing has stopped it.

Since the 1990s, spurred on partly by the example of Australian cinema companies, the US industry rediscovered its role as a special place, a sanctified ritual temple of spectacle and enchantment. It seemed as if fairytale and superhero blockbusters were the sure-fire superpower for permanent success. Certainly, the industry made a lot of money.

But now the whole edifice is feeling a dreadful tremor deep below the exhibition foundations. The blockbusters are moving to streaming, just when we all needed to hide at home, and somehow the disease leached away both our fervour and our tolerance for junk on the big screen.

Maybe this is the end of cinema as we know it.

The impact of streaming

The state of play is a mess. We have a huge choice of platforms, all pulling profit from each other, all trying to invest in keynote projects while the average budgets are dropping. Netflix is said to have a two-level approach between the spectacular branding projects and the commissions for local or segmented audiences – and they must be under pressure to change the balance.

For a while, studios were forced to put their cinema project straight to streamers, which they own anyway, then they tried cinema exclusives, or simultaneous day-and-date releases, or single licenses for world streaming rights, or accommodating festivals and local markets differently.

Every option has been tried, right down to chopping them into pieces for ad-supported exposure on YouTube and Facebook.

We notice how titles and franchises move to streamers. Star Wars is flogged to a paste on Disney+, Star Trek becomes The Next Generation on Netflix, Hogwarts becomes the originating myth for title after title, each more degenerate than the last.

Ideas, talented creatives, storyworlds, studio space, VFX outfits, veteran actors and fresh faces are all lured to streaming companies. But there is only so much talent in the developed world, and so many ideas in the Western canon.

The capacity to make worlds is being leached away from cinema, just as the box office figures we study show us that audiences want originality and reinvention.

The sad, clanking plod of the most catchy superhero behemoths is losing out to wit and cultural diversity as the audience seems to be growing up, or at least their inner children are feistier and more sybaritic.

Where that will get us is anybody’s guess.

Arthouse

For those of us who like artfilms and smaller pictures in the cinema with a group of people, this all looks pretty dangerous. I use the box-office figures to match the performance of Australian films to similar international pictures. Believe me, everyone is in the poo, and subtitles, great actors and festival success seem to make little difference.

Does this mean our audiences are changing? No, I don’t think so – the conversations about the films are pretty similar. The problem is the rise and rise of noise.

I put the last three years figures up because I think the titles show us something subtly important. I reckon you (and me) are more likely to recognise the titles from 2018 and 2019, than pictures made more recently.

They are not getting promoted and their names are disappearing into a different kind of advertising space crammed with unbelievable amounts of junk. Every time I have a conversation with people about enticing shows, we are picking our way through dozens of streamed series, each watched by only a few of us, and on a horrid variety of competing platforms. We just can’t talk to each other any more.

The agencies have encouraged creatives to travel, to become more cosmopolitan, and four of the seven films over that million mark this year have strong international connections. The sector has concentrated on skills development, while younger generations tend to be visual storytellers anyway.

But when I think about possible ways of improving our figures, I come back to that notion of noise. And no matter what we do to extract more local contact from streaming companies, the shows are still lost in the flood of global content.

So I reckon this is all a marketing problem. Let’s put the cash and training there.

The total list of Australian films

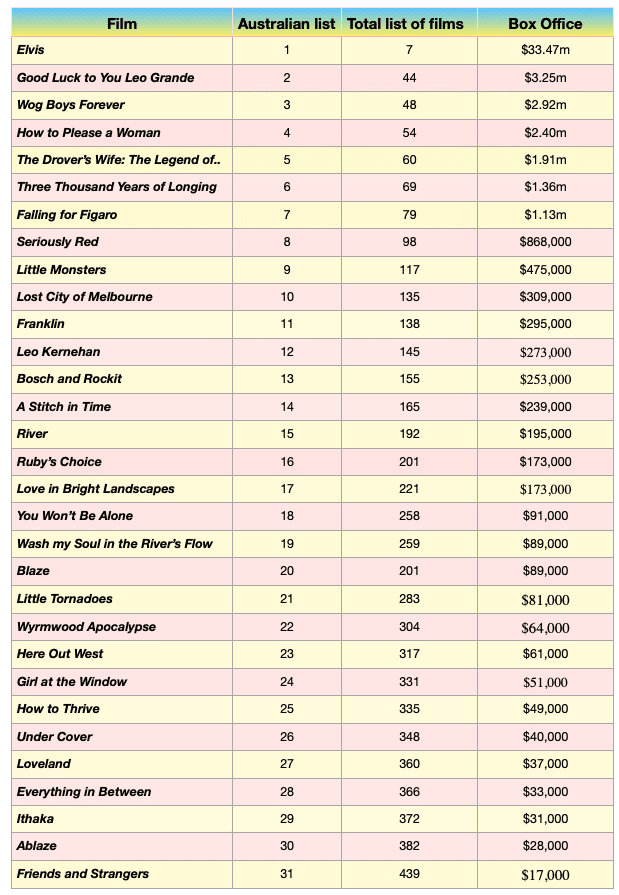

Here is a list of the 31 Australian films released this year that I can find in the source charts. Some extra films have only just been released while others were not reported at all.

There are many reasons why the films turn up in this order, which do not have anything to do with relative quality. Some have good marketing budgets, and maybe overseas campaigns rolled out locally. Stars may or may not catch the eye of journalists; films can be swamped by bigger films; they may go quickly to broadcast television or streaming.

So this chart is in no way a beauty contest, but it does show you what films can raise a marketing budget – and which ones no-one will bet on. Underneath it all is the fact that many of these pictures are niche films which are not considered to be worth supporting. In the marketplace, who wants to throw good money after bad?

Without marketing, you can forget about paying your investors from the returns.

Update: documentary Everybody’s Oma made $135,000, which puts the film at number 18 in the top twenty, and number 220 in the entire list of films. I knew I would miss something!

I have also adjusted the discussion about Leo Grande, because it is not considered by the producers to be Australian. I am setting the criteria very broadly because the definition of a nationality in globalised production is so chaotic. It would be more appropriate to explore the success of individual Australian directors and writers around the world but that would be an enormous task.

There is also an argument that $2.92m for Wog Boys Forever is a great result; it is not compared to the previous figures for the franchise, but the environment has become much harder.