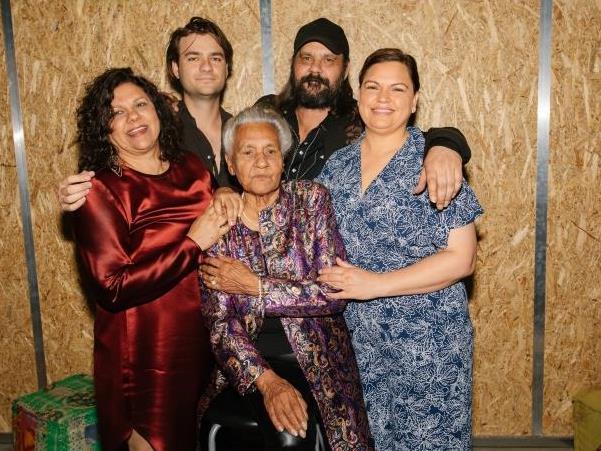

Image: At the gala premiere of ‘She who must be loved’ at the 2018 Adelaide Film Festival. L-R: Erica Glynn, Dylan River, Freda Glynn, Warwick Thornton, Tanith Glynn-Maloney. Supplied.

‘Getting on with it’ is a phrase that Freda Glynn uses over and over in her everyday conversation, whether she’s telling off her kids, batting away interviewers, or remembering her life as a single mother of five children during the 1970s. Apparently you just got on with it, whether that meant going to University in Adelaide at a time when few Indigenous people did, or being a senior bureaucrat lobbying Canberra for resources. The 78-year-old great-grandmother – who still mows her own lawn by the way – is humble and self-deprecating to a fault, as seen in She who must be Loved, a documentary about her life made by daughter Erica Glynn and produced by granddaughter Tanith Glynn-Maloney. It premiered at the Adelaide Film Festival last month and won the Audience Award for best documentary.

Meeting her now, you’d never guess that Freda was an Australian screen pioneer, one of the founders of the world-renowned Central Australian Media Association (CAAMA) and groundbreaking Imparja TV in Alice Springs in the 1980s. She certainly wouldn’t volunteer that information anyway. As she says in the film, she’s sick of talking about it and it was just one decade in a long life where her children were far more important. She happens to be the matriarch of a family that includes filmmaking offspring Warwick Thornton and Erica Glynn (who was Head of the Indigenous Department at Screen Australia from 2010 – 2014) and filmmaking grandchildren Dylan River and Tanith Glynn-Maloney.

Coinciding with the premiere of the film, the family as a whole was honored this year with the Adelaide Film Festival’s Don Dunstan Award. It’s usually given to an individual who has made an outstanding contribution to the industry, but exceptions can be made and there’s a good argument for that here.

The idea came to the festival’s Artistic Director and CEO Amanda Duthie on the red carpet in Venice last year at the world premiere of Sweet Country, which was one of Adelaide’s Investment Fund films. ‘I was watching Warwick Thornton and his son Dylan River [second unit director and DOP on that film] walking down the red carpet,’ she remembers. ‘I thought, damn, that’s father and son! How often does that happen anywhere? And they’ve made this incredible film together. That got me thinking about Freda and Erica and so many other people in this incredible family who are doing good work.’

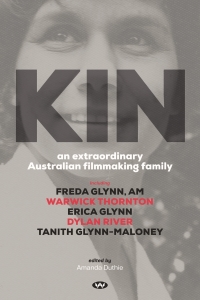

The previous two Don Dunstan awards (given jointly to critics David Stratton & Margaret Pomeranz in 2017, and to playwright and screenwriter Andrew Bovell in 2015) were accompanied by books of tribute essays published by South Australia’s Wakefield Press. This year that tradition continued, as Duthie set about commissioning pieces inspired by Freda Glynn and her family. She had no trouble convincing anyone to contribute. No matter how busy they were – and these were ‘all busy, busy people,’ she says, they leapt at the chance to be involved.

The 22 authors are a diverse and entertaining Who’s Who of Australian film, including, of course, David and Margaret themselves. Other big names include filmmakers Scott Hicks, Wayne Blair and producer David Jowsey.

Jowsey, the producer of Sweet Country (and a large slate of other Indigenous features and television), writes an affectionate essay about campfires and storytelling in the backyard. He observes the ‘rare as hen’s teeth talent’ on show in the family, and also offers an unexpected insight: that Warwick Thornton is an accomplished chef who loves watching TV cooking shows and may one day host his own. (We can’t wait.)

Rightly, there’s an emphasis on Indigenous writers in the collection, many of whom offer vivid memories and tasty anecdotes, painting a picture of a gregarious, generous and outspoken family. Deb Mailman thanks ‘Aunty Freda’, and talks about Erica and ‘Wok’; Sound recordist David Tranter remembers growing up with them all in Alice Springs, riding his bike and swimming at Wiggly’s waterhole, followed by dinner around the table with ‘Nanna Freda’, who always seemed to have extra kids there.

Writer Steven McGregor recalls being scared of Freda, and having Warwick ask him, ‘Have you ever been sacked by your mother?’ Warwick had. Three times.

In arguably one of the book’s most affecting pieces, Indigenous author Bruce Pascoe manages to be tender, poetic and political in his reminscences. ‘The whole family is a freak’, he writes. ‘Imagine Freda setting up CAAMA in an era where paternalism was still morphing out of disdain, where our pillow was still being smoothed for our passing. Imagine doing that black. Imagine doing that a black woman. A poor black woman.’

It would be easy for a collection like this to be overly adulatory and repetitive, like listening to the speeches at a wake or a birthday party. A few are a bit like that, but mostly they’re not.

There are some fascinating and important historical accounts, notably Philip Batty’s recollections of co-founding CAAMA with Freda, touching on the nuts and bolts of applying for funding and managing the organisation, as well as the fraught story of Imparja TV.

New York Anthropologist Faye Ginsberg recalls her long association with Freda, and the ongoing promotion around the world of Australian Indigenous screen stories, including Dylan River’s Buckskin at the Margaret Mead Festival.

Though the style of most pieces is conversational and colloquial, in keeping with the subjects themselves, there’s a dense and thinky piece by another anthropologist, Lisa Stefanoff, who uses the language of the academe to offer a history of how cameras were brought into the desert, enabling ‘survivance’ against the devastations of colonialisation. That’s one for the university readers.

The success story of Australia’s Indigenous screen sector is one of matching up smart policy, goodwill and great talent. It’s fitting that this collection includes generous (and not too press-releasy) pieces by former CEO of the Australian Film Commission, Kim Williams, and one by current Head of Indigenous at Screen Australia, Penny Smallacombe (who admits to being terrified of not doing justice to the subject). There’s another one by Bridget Ikin, former commissioning editor of SBS Independent, who helped bring Rachel Perkins’ first feature, Radiance (1998) into being, with Warwick Thornton as DOP. Ikin’s essay addresses Freda directly, saying: ‘You are the visionary matriarch with the powerful gaze and the canny wit…selfless encourager, and helpful cajoler.’ It’s very touching, as many of the pieces are.

Taken together these essays form an important and entertaining document about a very significant family in our screen industry, a family who seem to just get on with it, and make it look all too easy. In her contribution, Penny Smallacombe worries that the future filmmakers will look at the family’s legacy and think it was easy for them. ‘Trust me, it’s not,’ she writes. ‘Breaking ground never is.’

Thanks to Wakefield Press, Screenhub is able to offer an extract from the book, and it’s one of our favourite chapters. ’35,000 feet away’ is sound recordist Liam Egan’s contribution, giving a uniquely sonic perspective on making films with the family. You can read it here.

Kin: An extraordinary Australian filmmaking family (Wakefield Press), rrp AU$24.95.

Edited by Amanda Duthie, with contributions from Sandra Sdraulig, Deb Mailman, Bruce Pascoe, Philip Batty, Larissa Behrendt, Kim Williams, Steven McGregor, David Tranter, Lee-Ann Tjunypa Buckskin, Bridget Ikin, Margaret Pomeranz, David Stratton, Scott Hicks, Maryanne Redpath, PennySmallacombe, Lisa Stefanoff, Wayne Blair, Liam Egan, David Jowsey, Faye Ginsberg, Mary-Ellen Mullane, and von schtoop.

The documentary She Who Must be Loved, directed by Erica Glynn and produced by Tanith Glynn-Maloney is currently doing festivals and will eventually be broadcast on NITV.