I’m playing a game where two girls roam around a shopping centre. As we pass through clothing racks and jewellery counters, I keep an eye on my changing tally of money. My wallet is steadily growing though, because Jane Friedhoff’s Lost Wage Rampage isn’t a game about two girls shopping, but about stealing as much as possible.

Lost Wage Rampage is both playful and political. It shows how videogames are a fascinating ground for exploring girlhood.

The two girls are employees at the shopping centre who find that their male colleagues are earning higher wages. They resolve to take back their stolen wages by stealing a car on display and smashing their way through the aisles. Punk music blasts through the stereo as we crash through displays and swerve to dodge police cars. Friedhoff describes her game as ‘Grand Theft Auto crossed with Thelma & Louise.‘

It’s a fun subversion of the GTA series, but also to games made for girls that so often centre on shopping and consumerism. Lost Wage Rampage is both playful and political. It shows how videogames are a fascinating ground for exploring girlhood.

Friedhoff’s games, available on itch.io, are a testament to how varied perspectives like girlhood can emerge through the independent games industry.

Friedhoff’s games, available on itch.io, are a testament to how varied perspectives like girlhood can emerge through the independent games industry. Girl characters have come of age in some beautiful indie games over the last decade, like in Night School Studio’s Oxenfree, Polygon Treehouse’s Röki and Nina Freeman’s Lost Memories Dot Net. More girlhood games will be coming out of Australia soon too. Olivia Haines’ Surf Club and Ghost Pattern’s Wayward Strand are both coming-of-age games expected for release in 2022.

GIRLS IN THE MAINSTREAM

While games with nuanced girl perspectives have long come out of the indie industry, it now seems that major studios are finally catching up. In the last few years, teen girls have been featured centrally in more and more AAA and mainstream popular games.

Seeing girls at the centre of more mainstream games is culturally significant because it guides us to think beyond videogame’s strident association with boyhood.

The character, Ellie, in Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us series is probably one of videogame’s most visible teenage girls. The DLC Left Behind centred on Ellie and then so did the sequel The Last of Us Part II, cementing the idea that the series, taken as a whole, should be seen as Ellie’s story rather than Joel’s. Naughty Dog, however, hasn’t been the only major studio to realise that teenage girls make excellent protagonists. Take PlayStation Studios/Guerilla Games’ Horizon Zero Dawn or Dontnod Entertainment’s Life is Strange, released by the AAA publisher Square Enix, and even Marvel’s Avengers by Crystal Dynamics (also published by Square Enix) that put Kamala Khan at the centre of its story campaign.

READ: The Last of Us Part II’s easter eggs prove that all games are personal games

Seeing girls at the centre of more mainstream games is culturally significant because it guides us to think beyond videogame’s strident association with boyhood. This association has largely been informed through the medium’s surplus of masculine heroes, as well as the gendered masculine traits, like aggression and violence, that have traditionally characterised play.

Games with girlhood themes also prompt us to consider girls in games outside of games deliberately designed for girls, often referred to as “pink” games. “Pink” games tend to promote tiring stereotypes while relegating girlhood to the periphery of gaming culture. The presence of girlhood in mainstream games begins to rewrite all of these gendered assumptions about games and games culture.

Play systems have the potential to elicit coming-of-age anxieties: from fear, frustration and boredom, to playful joy and rebellion.

THE PLAYFUL STRUCTURES OF GIRLHOOD

But what does girlhood in a videogame format look like? Games are a distinct medium for exploring girlhood themes because players take on an active role in resolving the adolescent challenges and trials. Play systems have the potential to elicit coming-of-age: anxieties from fear, frustration and boredom, to playful joy and rebellion.

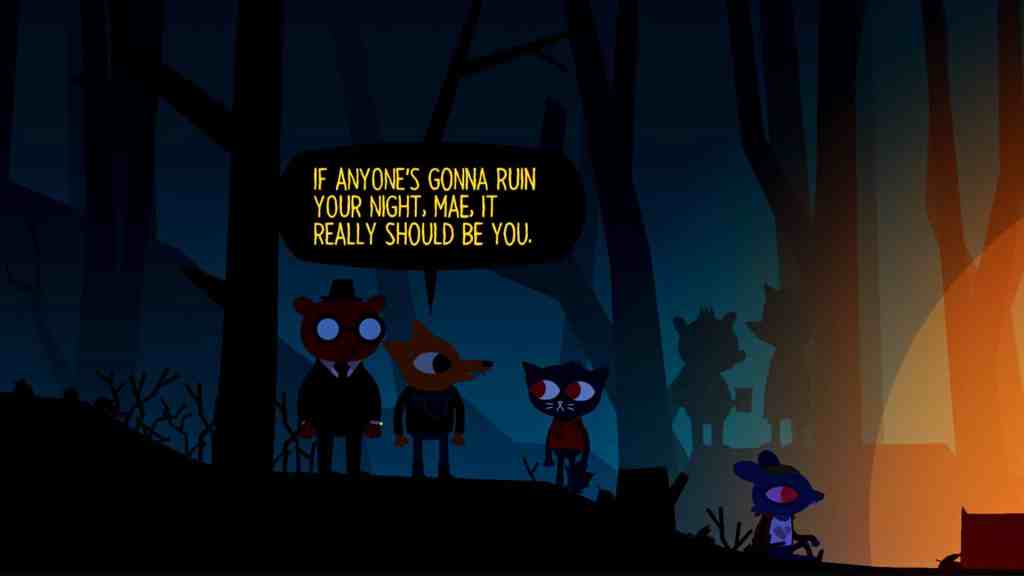

Tensions around boredom and entrapment, for instance, come through in games like Night in the Woods and A Short Hike. These games have very straightforward objectives, but we’re free to wander or explore for the simple sake of curiosity. For the (anthropomorphised) girl protagonists, the available space is restrictive: Mae from Night in the Woods is trapped in her small rural town and Claire from a Short Hike is forced to go camping with her aunt. These games produce a compelling sense of adolescent restlessness. But at the same time, they also celebrate the freedoms of having fewer responsibilities and the magic moments to be discovered when embracing feelings of boredom and curiosity.

READ: Night in the Woods captures bittersweet millennial life under COVID-19

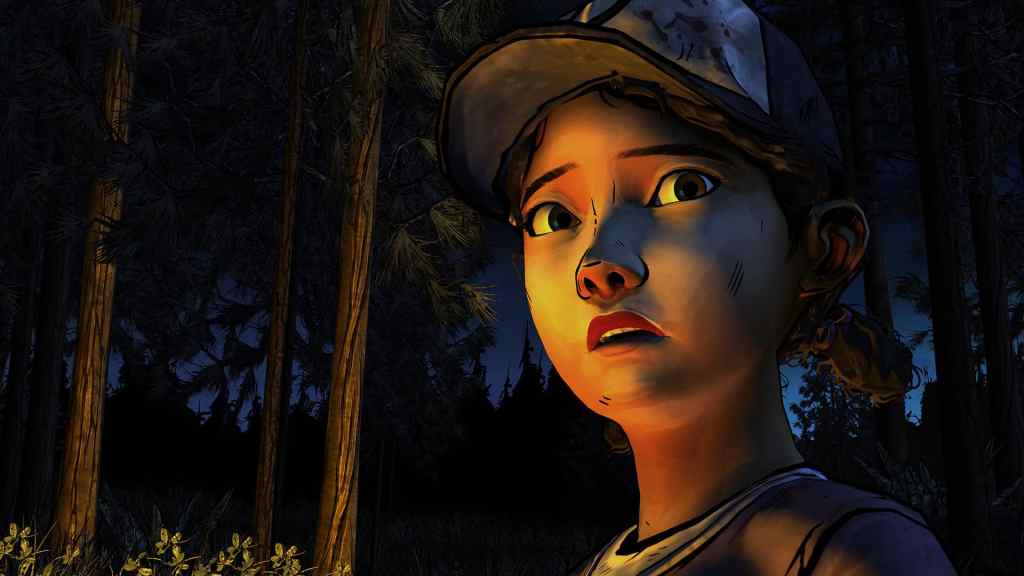

Meanwhile, when I play Telltale’s post-apocalyptic The Walking Dead: Season 2 I share in Clementine’s fear of “walkers” and the equally dangerous humans that dissolve any secure sense of safety. Just as frightening, though, are the outcomes of my decisions and the weight of Clementine’s increasing agency as she grows older.

Adding to the pressure, the group of survivors continually uphold Clementine as a beacon of virtue and hope for the future (something we see today through the teen girls leading climate change action). When games with decision-making at their centre feature girls’ coming-of-age stories (and this is central to Life is Strange too), it’s easy to reflect upon our own internalised pressure to make the right choices when newly acquainted with independence – as well as the expectations placed on girls to remain morally upright.

GIRLS AS ANTI-HEROES

The Last of Us Part II subverts this by positioning us to perform the anti-hero through Ellie. It maintains a serious tone like The Walking Dead, although there’s something nonetheless playfully transgressive in taking on the perspective of a teenage girl who violently operates on the outside of a broken society. Lost Wage Rampage on the other hand removes the seriousness altogether and presents the utter joy of claiming justice through destructive anarchy. In this instance, girl defiance and a driving videogame come together to create humour and delight.

New meanings emerge when teenage girls occupy central roles in genres that are typically rooted in boyhood culture, like action-adventure or driving games. We experience different forms of pleasure and empowerment when playing as girl characters that boldly take up space or that resist conventional performances of femininity. And they need not always be overtly radical or political. Videogames can convey sincere coming-of-age relationships, stories, and feelings that even adults are liable to relate to.

I’ve felt a particularly powerful connection to Life is Strange: Before the Storm which is a prequel to the first Life is Strange game. I adored playing as the misunderstood rebel Chloe Price and sharing her impassioned frustration towards almost every adult in her life. I especially felt a sense of adolescent intimacy resurrected when wandering around Rachel Amber’s bedroom. It reminded me of the care and affection I would feel when learning about a new friend through the artifacts in her personal sanctuary, and the trust we impart when inviting someone into our own.

Coming-of-age games also remind me that identity construction is an ongoing process. As I navigate my late-twenties, my future remains uncertain as I’m still discovering my sense of place in the world. This is likely why I’m so drawn to coming-of-age themes in the games that I play. It truly excites me to see girlhood themes receiving more visibility and value. I look forward to the promising possibilities that may surface as games continue to explore girlhood further.