By Viktoriia Grivina, University of St Andrews

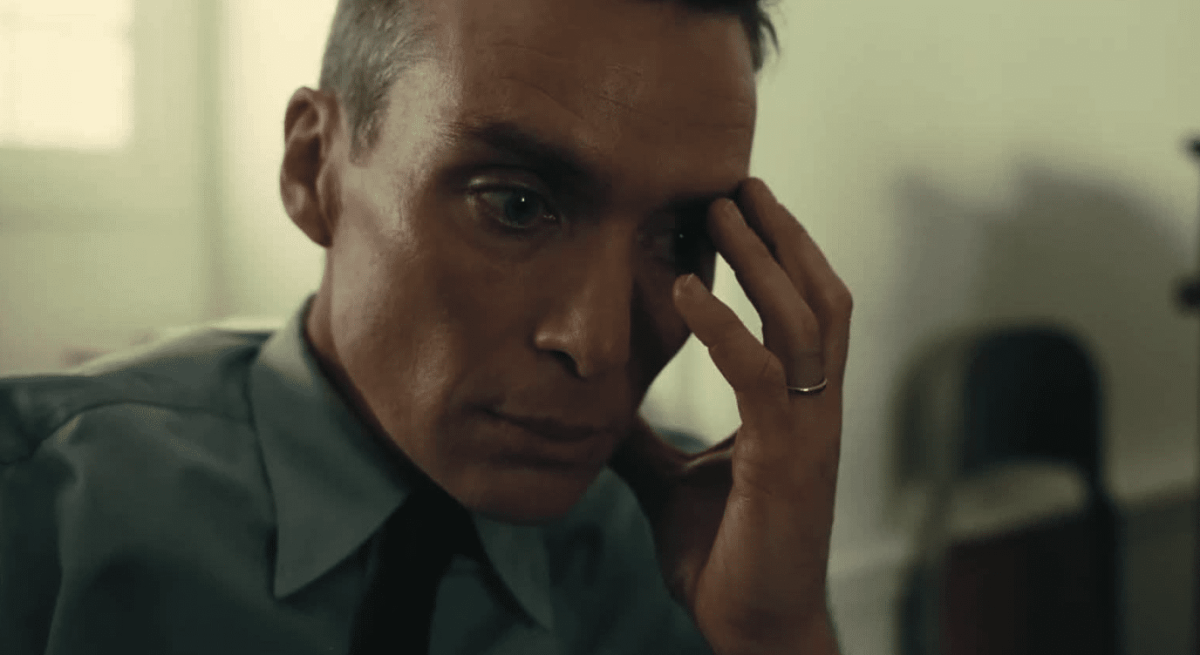

Following the recent release of Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer continues to infuse 2023 with atomic energy. Stylistically, of course, the two couldn’t be more different. What Anderson shows as a blast outside a diner’s window that doesn’t so much as interrupt the characters’ coffee, Nolan shapes into a three-hour epic. And as a Ukrainian, I am grateful for that.

While daily life in the war-time state constantly fluctuates between feeling like a farce and a Greek tragedy, Oppenheimer emphasises the real level of the threat – something I often feel western Europe and the wider world don’t fully grasp.

Nolan’s Greek tragedy is the world that I live in. Watching Oppenheimer from my local cinema in Kharkiv I hope that – to a smaller degree – a global audience will experience Ukraine’s everyday anxiety too.

Nolan’s use of sound is what makes his take different from the many other Oppenheimer biopics. So much so that I would see it in the cinema again, purely to focus on how various pieces of music, noises and silences guide the viewer’s attention.

As my seat shakes from the stereo effects, nobody in the nearly full cinema flinches. The teenagers to my right are as used to explosions as J. Robert Oppenheimer himself. The moments of silence (a Nolan trademark) however, feel ominous.

Read: Oppenheimer review: Nolan approaches the sublime

It is said that you will never hear ‘your’ missile – the one that kills you. Locals in Kharkiv use this wisdom to calm our nerves after hearing a loud explosion. As we sit through the nearly three-hour film, our only wish is not to hear the bomb siren sound outside, since it would mean we would have to leave the cinema and go to the underground shelter.

Granted that in a city so close to the border, shelters aren’t of much use. It takes about 30 seconds for an S-300 missile to fly from the nearby Russian town of Belgorod, meaning we often hear the siren after the blast. Unsurprisingly, explosions sounds are a leitmotif of the film too, making its soundscape very relatable.

What Nolan gets wrong

The overarching motif of Oppenheimer is a warning against the precarious reality that Ukrainians live in now. As one great scientist notes to Oppenheimer: ‘we now enter a new world’. The warning shapes the symphonic structure of the film which is, perhaps, the most mature of Nolan’s works.

Oppenheimer is true to Nolan’s greatest cinematic talents. But it speaks to his weaknesses as well. Oppenheimer’s children don’t get any screen time, but are shown through a nagging baby cry. The women fall similarly short of becoming real, depicted simply as dedicating their lives to Oppenheimer.

I appreciate Nolan not trying to crawl into someone else’s skin, instead opting to explore the perspective (that of a white, privileged man) he can personally empathise with. But as a viewer watching from the other side of nuclear anxiety, I found the film’s depth of representation lacking.

Nolan’s wide strokes, though powerful, miss detail. The USSR is called ‘Russia’ and Soviet scientists are called ‘Russians’ throughout the film. Watching it several kilometres from a Ukrainian lab where the first lithium atom in the USSR was split, this feels ironic.

The massive shelling of the nuclear research reactor by the Russian military in 2022 created an uproar in my local community precisely because so many people here have family and friends who work in physics. Ukraine’s nuclear research programme, which had been a subject of great pride, was now endangered. In painting all the scientists in the film as Russians, Oppenheimer ignores the work of historic Ukrainian physicists.

Read: Oppenheimer – cheat sheet

In the end, Oppenheimer is not a film about historical accuracy or justice, but rather a great emotional and sensory experience. And for a summer blockbuster, what more can we ask?

As I walk out of the cinema, the siren starts to roar, signalling that somewhere in the depth of Russia, a fighter jet carrying ballistic missiles has taken off, harmonious with the last scene of Nolan’s film.

I walk through the warm summer evening, feeling strangely more like a Wes Anderson character than a Nolan one. Perhaps, I think, if the explosion blasts behind my back, I won’t even drop my mint lemonade. Because I already live in the “new world” of dark nuclear absurdity – one that even Oppenheimer himself could not possibly have predicted.

Viktoriia Grivina, PhD Candidate, School of Modern Languages and Social Anthropology, University of St Andrews

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.