The arts are a lifestyle choice, says Treasury. Down the pub we are called a bunch of wankers, at career guidance sessions parents beg their children to be sensible. At the same time, audiences and the media valorise success. The publicity system shows us glamour, red carpets, and international competitions. Winners are stroked unconscious on breakfast television.

But most artists are invisible. The Show Must Go On is a local documentary that interviews dozens of working artists to explore the psychological impact of working in the arts. You will read these figures a few times in the advertising campaign before the film is broadcast in Mental Health Week on the ABC.

Amongst the 42,000 people who work in the Australian entertainment industry, anxiety symptoms are 10 times higher, sleep disorders are 7 times higher and symptoms of depression are 5 times higher than the national average. Suicide attempts in the industry are double the national average.

The price of success

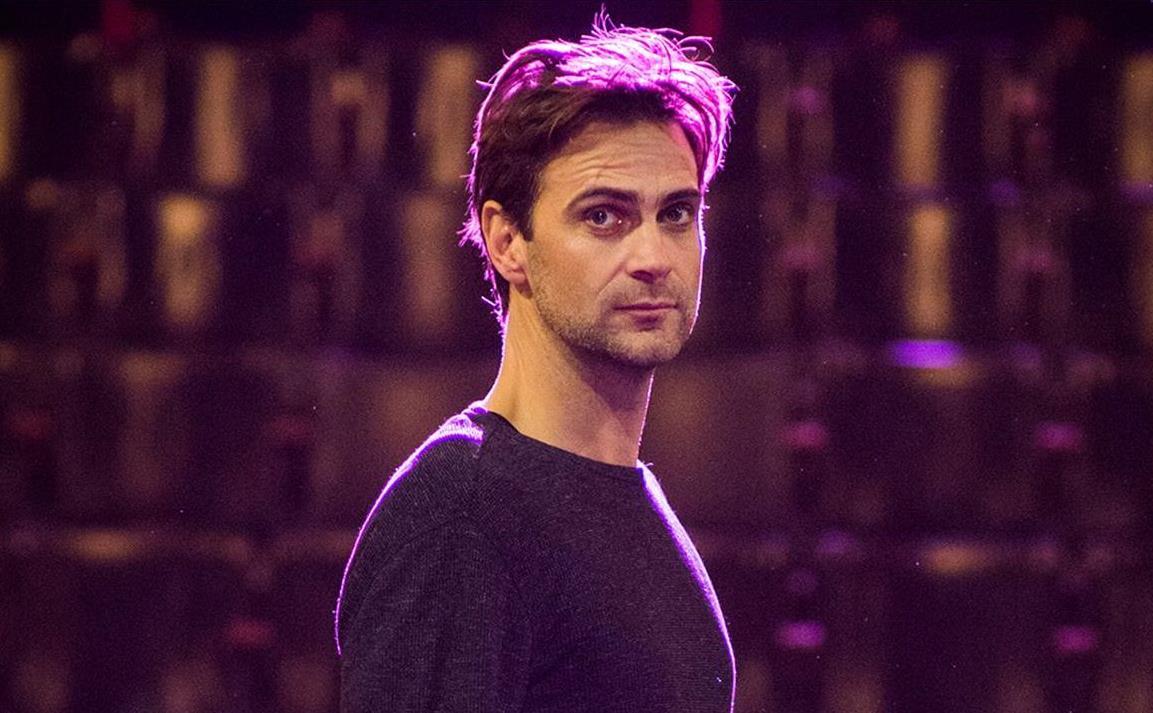

Ben Steel became abruptly successful as Jude Lawson on Home and Away, where he was a regular between 2000 and 2002. ‘Fame is a really weird thing,’ he acknowledges. ‘When you are on a show like Home and Away, you are in people’s homes four days a week. There is nothing that can prepare you for the instant fame when you get cast on these shows.’

When it ended, he dropped off into nowhere. ‘I wanted to be an actor ever since I was a kid. My worth was tied up with what I was doing, which falsely gave me the feeling I was really worth something. That is a problem when it comes to an end, and it is hard to explain how that feels.’

He worked in the UK and came home after nine years, aching to reconnect. ‘I had been watching the industry change in that decade,’ he says, ‘and discovered the door was firmly closed against me.’

Like so many artists deprived of regular work, he went to a really bad place. There be the monsters of depression, despair, confusion, self contempt, thoughts of suicide – all seen as individual problems. Anything that seems crazy is a humiliating secret. Even worse, these issues spill into families and lovers, cutting income, freezing emotions, creating a grey fog of negativity.

‘I was a bit like a zombie for months and months. Every bad thing pushed me further and further down into an endless spiral. Every time I thought my gut was twisted as tight as possible, there was another knot. it was a terrible time which for the life of me I couldn’t get through.’

Sharing the truth

He saved himself almost by instinct. He found a camera and began to interview other creative people with the same problems, until he had sixty personal confessions from people willing to tell their intimate stories to strangers. Among the people describing how they survived are actors Sam Neill and Michala Banas, writer and director Jocelyn Moorhouse, dancer and artistic director David McAllister AM, actor, director, writer, and comedian Shane Jacobson, singer-songwriter Dean Ray, and author, screenwriter and script producer Sarah Walker.

Steel was pushing himself, finding the right people, developing their trust, seeing his journey in their tracks. ’Maybe the blessing was that work was my only focus. I had the documentary and I kept doing it. Even when I felt like not getting out of bed I kept turning up and filming and then editing. It gave me motivation.’

He showed the footage to venerated documentary and drama producer Sue Maslin who was overwhelmed by the truth of the stories.

‘I decided we had to put everything aside, we had to help Ben tell this story,’ she says.

‘I discovered from Ben’s interviews the level of anxiety grows with the level of success. All could be over in a moment, because that’s how the business works. Continual rejection is built into the job description. It is a reality we have to take into account and develop the resilience.

‘Documentaries are not possible without courage. This film kicked off from Ben’s courage in reaching out to others to make sense of this insane business we find ourselves part of. Reaching out was his moment of resilience. It worked precisely because he was on the journey himself.’

The ultimate responsibility

Ben Steel learnt a hard lesson. ’I am ultimately responsible for certain events or situations. We might not have started it, but how we relate to it is definitely our responsibility. It was hard for me at my darkest to really hear this. We can control how we react to events or situations and some of those negative feelings are indicators or lessons. You can’t be up all your life.’

The pain of rejection led him to challenge his way of seeing himself. Don’t concentrate on your own mistakes. Don’t feel rejected and persecuted. Why do you put such value on this one aspect of your life when it is so much wider?

‘To focus on a creative life, we need to be creative every day. We can make sure we are inspired by reading novels or music or articles – we can wake up happy and proud. We have to own that we make money from a variety of sources while we aim for the more important success.’

To Sue Maslin we are all on a continuum of anxiety, depression and ideation. They become very painful when they are extreme, and the intensity is built into the structure of creativity in our society. ‘It has a physiological dimension too,’ she says. ‘We work with unbelievable intensity and then suddenly we are on our own. We have an adrenalin deficit and we all feel really flat and have to work out how we pull out of it.’

Steel was particularly surprised by the dimension of time. He is now in his forties, no longer a wild young star and ‘edging towards the magic number fifty. I heard over and over again that your career is over then. I expect that to some extent for performers, particularly women. Audiences want to see young, sexy people.

‘But behind the scenes that magic number fifty still rings true. You can have decades of experience, know the job inside out, be the master of your craft and you can’t get a job to save yourself. I don’t get it.’

There is no shame in the roller-coaster emotional life of creativity. When we talk about it, as The Show Must Go On does, we discover we all feel this way at times, and crawl out of our pits and go back to work.

It is possible to find balance, the ability to accept the myriad forces beyond our control. Just as the film moves towards release, Sue Maslin has managed to get Ben Steel to go surfing. He is not very good at it, he admits with the sound of the sea behind him on the phone, but he really loves surfing and he has some good years left.

The documentary will screen on Tuesday October 8 at 9.30pm on ABC + iview. Running alongside the release of the film will be a national Wellness Roadshow that will be launched in major cities across Australia from October 2019. The initiative will be launched on Wednesday October 9 at Arts Centre Melbourne.