In a poem published in Running Dog last month, I write about my frustration towards news cycles. I write, it is always about footage. It’s never the violence itself that outrages the masses, it’s the video evidence of it. I see it in everything, not just in the context of Palestine: you can’t get people to care unless they can physically see what they’re caring about.

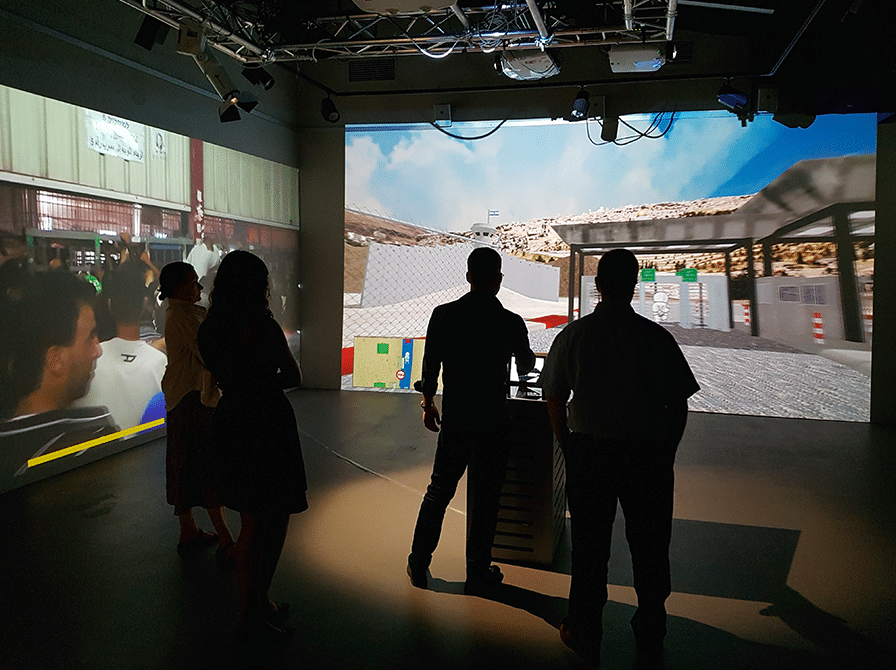

Rusaila Bazlamit launched Re: Visit Palestine in 2016. It’s an interactive installation that addresses the occupation of Palestine. The installation is made up of three wall-video projections. The central projection is an interactive virtual environment that you, as the user, can move through using a controller in the middle of the room. The two peripheral projections play videos prompted by certain points in the player’s movements on the interactive screen.

Re: Visit Palestine follows a traditional narrative split into three locations to represent the exposition, conflict, and resolution. (1) Jaffa, now a part of Israel-proper, represents the 1948 Nakba and the creation of the state of Israel, (2) Jerusalem depicts the manifestations of living under occupation and apartheid, (3) Gaza focuses on the blockade that Palestinians have been enduring for the past 14 years, at the end of which the user finds themselves unable to move forwards or backwards – trapped in the limbo of no resolution.

Palestine’s digital archive means the world to me because it exists in a geography entirely its own. One that is not vulnerable to colonial destruction. It cannot be looted or bombed.

The path is intentional. It recounts the occupation of Palestine from its beginning to the present. It gives users a hindered freedom of movement; they can keep engaging with the geography but not without frustration.

Before I went to Palestine for the first time, everything I had seen of it was digital: documentaries, movies, photographs, but none of them my own. We did not have family photos or records. My great-grandfather was a poet but his oeuvre had been destroyed by Israeli militia in 1948. Palestine’s digital archive means the world to me because it exists in a geography entirely its own. One that is not vulnerable to colonial destruction. It cannot be looted or bombed.

All the videos in Re: Visit Palestine’s peripheral projections are created by Palestinians on the ground. They share personal stories and lived experiences related to the locations that prompt them.

Palestinian archives don’t have the privilege of being stored in museums and monuments, supported by governments and the help of large funding bodies. There are no spaces to physically enter, walk through, and eventually, leave: there is no monument built to remain. We turn instead to guerrilla memorials. We rely on the digital age to power them.

Before I went to Tarshiha, where my grandmother is from, I read the Wikipedia page. Before I went to Hittin, where my grandfather is from, I went to Palestine Remembered and scrolled the 138 photographs of Hittin uploaded by different users.

Palestinian archives don’t have the privilege of being stored in museums and monuments, supported by governments and the help of large funding bodies. There are no spaces to physically enter, walk through, and eventually, leave: there is no monument built to remain. We turn instead to guerrilla memorials. We rely on the digital age to power them.

Read more: What are games for, if not community, collaboration and creativity?

Re: Visit Palestine creates temporal and mobile spaces that don’t need established buildings in order to exist. Far from being a memorial built to remain, it is purposefully fluid, because the Palestinian struggle is not stagnant, idle, or over. The footage in Re: Visit Palestine is constantly updated as the fight progresses. The components can be sent to anyone and installed anywhere. This too is what makes the structure a guerrilla memorial. It makes use of our available resources, and our resources too are fluid.

I used to think of the internet as vast for this reason; I could sink into footage of my displaced geographies. I could move through the digital space with no roadblocks. But there is slippage in that. What happens when I reach the 138th photograph? Where to next?

People talk of game spaces as escapist, or liberating: infinite and procedurally generated geographies mean the world is expansive as you decide to be. Re: Visit Palestine rejects this idea and builds a clear path to follow, one you are restricted from straying from.

There is a careful balance that we need to strike with politically engaged works. I talk so often about Palestinian rage. We need to be angry enough that people care, but not so angry that it scares them away. We need our narratives to remain inviting, otherwise, we’ll have no newcomers.

Re: Visit Palestine can be installed anywhere because of its universal hardware – three wall projections and a Leap Motion Controller are quick and easy to bump in, the work doesn’t need more than a room with three walls. But it’s more than the hardware of the work that makes it accessible for public installation.

The Palestinian struggle so often gets co-opted and mutated into something “too dense” but through its streamlined path, Re: Visit Palestine tells an uncomplicated story of occupation to those not yet on-side. There is no way to playthrough and leave undecided where you stand.

Part one of Re: Visit Palestine is in Jaffa and part three in Gaza. Both on the eastern coast of Palestine, you start and end at the sea. It is a work barricaded in space but still bookended by desires of fluidity.