Much has been said of videogames and 2020. As our social lives moved from parks, galleries, pubs and libraries to Among Us and Animal Crossing, many praised videogames as social spaces. In a year that offered serious challenges to people’s mental health, games were also form of escape. They gave us comfort; they made us laugh. Aotearoa entered 2020 still reeling from the shocking eruption of Whakaari, and most of Australia was on fire; over the year, both countries have experienced hard lockdowns in response to the pandemic, which, while incredibly effective, took their toll on us financially, emotionally, socially. If this was a year when we needed a little joy, local videogames certainly gave us that. But many on this list showed us that games can do much more than that, too.

Many of the best local games of this year speak directly at our biggest challenges, our pain, our fears. Rather than distract us from those feelings, they accompany us as we feel them. They offer us a way in, not a way out. It’s an opportunity unique to an interactive medium, and many of these games approach that opportunity in remarkable and groundbreaking ways.

Umurangi Generation, Veselekov

I have to start with a game that might be my favourite of the year: Umurangi Generation. On its face, Umurangi Generation is a first-person photo-taking game set in the psychedelic, dystopian future in Tauranga, Aotearoa. At each new location, the player is given photographic ‘bounties’ to fulfil, which guide the player through the level, encouraging them to take creative photos, which can be customised and finessed to a remarkable degree. The game doesn’t reward artistic merit per se, but the electrifying art style, and sandbox-style play work together to encourage reflection and thoughtfulness, which creates a more conducive creative environment than a rewards system ever could.

It is also a deeply radical game that centres the Indigenous gaze; developer Naphtali Faulkner’s Ngāi Te Rangi heritage shows through at every level, from the intricate street art that adorns the walls around Tauranga, to the antifascist and anti-colonial sentiment that underpins the game’s design. Without relying on dialogue, the game prompts players to look more closely at the world, and the power relations around them. As a work of Māori science-fiction released during a global pandemic and the global Black Lives Matter movement, it couldn’t be more expressive of 2020, a year that demanded protest, and also demanded our witness.

As Edmond Tran wrote of the game for Screenhub earlier this year: ‘[Umurangi Generation] is a game whose mechanics encourage the player to look with intent and a discerning eye, identifying clues in the environment that hopefully spark revelations about the greater context of the world. It’s an aptitude Umurangi hopes the player retains in everyday life.’

Check out Umurangi Generation on Steam.

Check out Necrobarista on Steam or Itch.

Terracotta, Olivia Haines

In a year when I turned to art for comfort, understanding, and company, Terracotta was an important personal favourite of mine. In this tiny game by Olivia Haines, you go on a short walk around a beautiful, pastel-rendered neighborhood, in only the company of your own thoughts, which appear unintrusively as text on the screen. Haines’ art style strikes a perfect balance between being completely her own, and deeply welcoming. It’s a remarkable achievement from an artist whose work has long considered the relationship between technology, home, and femininity.

When I first played Terracotta, I was immediately transfixed by the way Haines can create these environments that feel compete and unique, while also feeling incredibly familiar. This feeling has remained, and during the pandemic, that sense of ‘intimate insight into the experience of the main character, her mental state, and how she processes and copes with the world around her’ only felt more poignant.

Developed in response to the pandemic lockdowns, Terracotta is a beautiful, heartfelt reflection of Melbourne life in isolation, and will always hold a special place in my heart.

Moving Out, SMG Studios

In a year when we all stayed in, Moving Out offered people a new way to play together. With fun, candy-bright graphics and a wide range of accessibility features, Moving Out is a local co-op game designed to be played by the whole family – from little kids to grandparents. The game took out the gong for AGDA’s Game of the Year, and quickly became a beloved to many households.

As a father himself, SMG Studio’s CEO Ash Ringrose told Screenhub that he was proud their game could offer a new form of social play for so many, during a period of isolation: ‘We’re motivated by what we can contribute to society, and the fact that our work makes people happy, and can help people deal with the stress and boredom a little more easily.’

Check out Moving Out on Steam.

Best Friend Forever, Starcolt

If you love dogs, gays, and a little wholesome yearning (and really, who doesn’t?), Best Friend Forever is the game for you. It’s Starcolt’s debut game. (Studio Lead Lucy Morris detailed the experience of launch on Medium and on Screenhub.) Best Friend Forever is a dog adoption and dating simulator, set in the sunny town of Rainbow Bay. As the name of the town suggests, the game is queer-friendly, offering the opportunity to date people of all genders, and deeply wholesome.

The studio is led by women, and foregrounds an ethic of care in their studio practice; this compassionate and thoughtful approach also apparent in the game itself, which is centred on adopting healthy breeds of dogs, rather than purchasing designer breeds with hereditary health issues. The team consulted with vets to ensure that they were doing dog representation right, and this is evident through in the idiosyncratic, personable hounds that grace the game.

Having a dog that wants to bark, sniff, snack, or occasionally wee on things is a lively and fun addition to classic dating sim gameplay. I picked it for our monthly What We’re Watching column back in September, and I still think about the time I spent in Rainbow Bay with immense fondness. If you’re looking for some pure wholesome fun, I can’t recommend it more highly.

Check out Best Friend Forever on Steam.

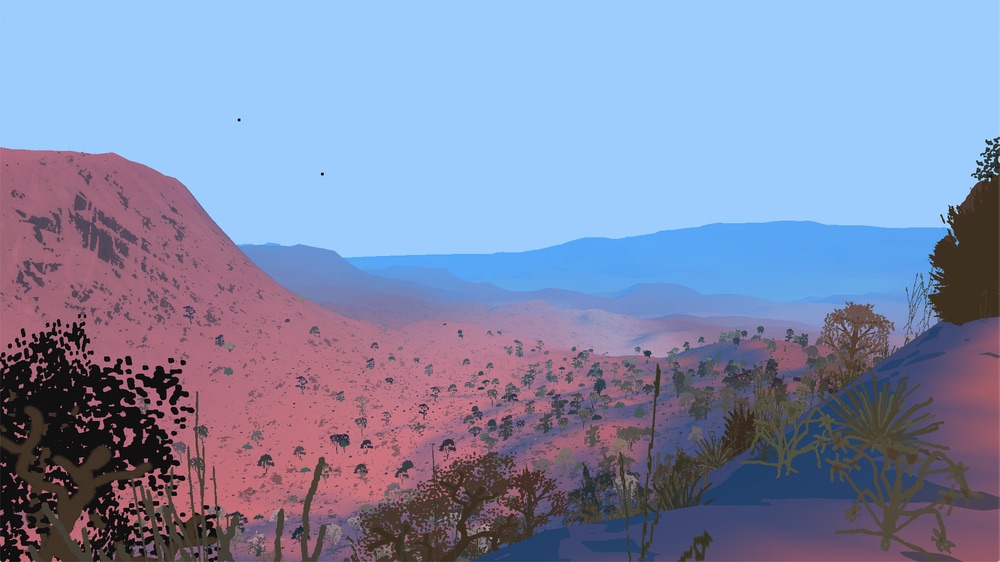

Red Desert Render, Ian Maclarty

Some of my favourite games are fan games. Toby Fox’s Undertale was inspired by the Earthbound series; Stardew Valley was inspired by Story of Seasons; Team Fortress was first developed as Quake mod, and PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds was based on designer Brendan Greene’s experiments with Arma 2 & 3 mods. And in that same fine tradition is Red Desert Render, an exploration game by Ian Maclarty based on his time in Red Dead Redemption II.

Published on Itch.io, a platform Maclarty has long been an advocate for, Red Desert Render is an experimental exploration game. In some ways, this feels like the most personal game I’ve ever played. It doesn’t have an overt narrative, but it’s shaped by Maclarty’s explorations of RDR2, an experience he shared with the rest of ‘The Grannies,’ a nickname given to the small group of game devs who would meet up to explore the ‘out of bounds’ areas, the backstage parts of the game not intended for player access that could only be accessed through glitches, loopholes, and a little bit of luck.

Red Desert Render’s spiritual recreation of those adventures isn’t just interesting on a technical and artistic level: it also feels generous and intimate. Whether you choose to play solo, online multiplayer, or local co-op changes the experience significantly – but that intimate sense of having been invited to look into someone else’s world remains.

The out of bounds adventures of The Grannies made me feel more excited about metagaming than ever; and Red Desert Render makes me excited about the future of game-making, too. This medium is rapidly changing what a piece of non-fiction art can look like, and I’m so excited to see what comes next.