‘This weird time demands we be real about who and where we are, and that we have the creative courage to make stories that reflect that reality,’ says Samantha Lang. Like the rest of us, she’s been doing a lot of thinking and worrying since the pandemic struck. But her focus is mainly on positivity, advocacy and using this time to re-think the ways we work.

Back in 1997 when she was still in her twenties, Lang’s first feature film, The Well, competed for the Palme d’Or, arguably the world’s most prestigious film prize. ‘It’s hard to top having a film in competition at Cannes as a very young woman – and a film with an all female cast and largely female crew,’ she says when asked about her proudest moments.

Lang is quick to add, however, that she’s ‘equally proud of the achievements of all the film and television students I’ve taught who have gone on to realise their own ambitions, and also of what the Australian Directors Guild has accomplished for women and directors from underrepresented groups in the five years that I’ve been president.’

Since that shiny debut at Cannes, Lang’s creative career has been impressively varied, directing and producing features (The Monkey’s Mask, and French film L’idol), television drama (My Place), telepics (Carlotta, The Killing Field), documentary (It All Started With a Stale Sandwich) and a number of VR projects. She’s currently working with director Garth Davis (Lion) and producers Emile Sherman and Iain Canning setting up a slate of projects across film and TV for their new company I AM THAT, as well as developing an adaptation of Nakkiah Lui’s play, Kill the Messenger.

But it’s a different kind of creativity involved in Lang’s roles as Head of Directing at AFTRS (2010-2016), and as President of the board at the Australian Directors’ Guild since 2015, where she was one of the founding members of Screen Australia’s Gender Matters Initiative, that gives her a unique perspective and broad overview on the Australian industry. Starting as a stills photographer, she not only knows what it’s like to spend long days on set, trying to combine family and work, but also knows intimately the nitty gritty of committee meetings and bureaucracies and the slow grinding paperwork involved in systemic change.

In the lead up to the 2020 Australian Directors’ Guild Awards, we caught up with Lang to get her perspective on the industry right now, her pet peeves, hopes for change and advice for those just starting out, bless them.

Screenhub: How have you experienced this unusual year so far?

Samantha Lang: In 2020 we’ve been affected not just with COVID, its impact on our physical, mental, cultural and social lives, but by the bushfires and Climate Crisis, the Black Lives Matter movement, the US presidential elections, and the souring of diplomatic relations with China. In these turbulent times, it’s made me (like so many others) question what’s important professionally, politically, personally – and try to take some responsibility by acting on the pressing issues of sustainability and inequality at a micro and macro level – while maintaining a sense of joy and appreciation of what we still have and can still do.

So it’s been a time of reframing – revising strategies and priorities around what projects to develop. I’ve been asking myself so many questions: What are the stories that people are going to want and need as we emerge, reconfigured, from this encounter with the pandemic? Beyond development, what is the re-think on how those stories physically proceed into production, not only in terms of logistics but also finance and distribution? And how will the cinema retrieve its former allure as a big event experience? Can we still make great movies and TV that serve a home audience amidst a cluttered SVOD landscape?

‘What are the stories that people are going to want and need as we emerge, reconfigured, from this encounter with the pandemic? Beyond development, what is the re-think on how those stories physically proceed into production, not only in terms of logistics but also finance and distribution?’

– Samantha Lang

This is a crucial time in our industry to look back while moving forward – to embrace scale and stakes on the screen – to look to Speculative Fiction, Diverse Characters and Big Themes. Now is the time to inject our narratives with old fashioned qualities like kindness, generosity and love – to stay grounded in our humanness – while recognising that the future will be full of innovation, new technologies and a different way of existing on the planet.

When I think about George Miller and his Mad Max series, he was so way ahead of the curve. He is our cinematic equivalent of a writer like J.G Ballard. A filmmaker like George should be a great source of inspiration to us. Bold, resourceful, adventurous, passionate. Or Tracey Moffat, a filmmaker and artist who was creating new ways of expressing her lived experience as an Indigenous woman in Australia decades ago with her films Nice Coloured Girls and Night Cries.

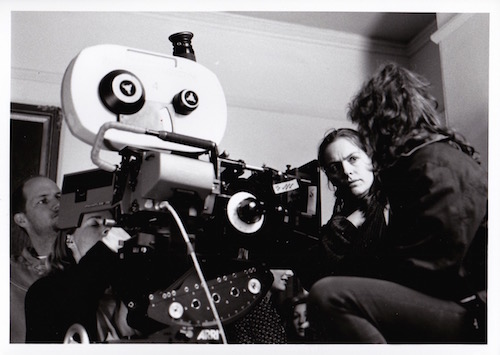

Image: Lang on the set of The Well with DoP Mandy Walker. Photo credit: Elise Lockwood.

You’ve been ADG president since 2015. What are the main issues or problems that Australian directors face at the moment, and how are they different from when you were a young director just out of film school?

In 2015 when I came on as president, it was before #MeToo had exploded but when the conversation about the lack women directors in industry had started and people were calling for quotas. Anna Serner, the CEO of the Swedish Film Institute, was a big influence. So Gillian Armstrong, Rebecca Barry, Ray Argall, Michela Ledwige, Anna Broinowski and Megan Simpson Huberman and I formed a small ADG group to advocate for an uptake of greater diversity in producers’ choice of directors on productions, whether feature film, TV series or commercials. Deanne Weir and Monica Davidson had already been doing a lot of work in this space, as had academic Deb Verhoeven. I took on the president role because my ambition was revitalise the guild in terms of its membership and its cohort.

Read: Give female DPs a go: Carolyn Constantine ACS

Beyond women, there was so much work to be done in terms of underrepresented groups – LGBTI, race, class, disability, regional and their intersections. My goal for the ADG was to broaden and support directors across a greater breadth and depth, industrially, professionally and culturally. I also like to focus on what I see as opportunities for directors and ask: What can we do differently as storytellers in Australia at this moment of disruption? For example, there has been a proliferation of webisodes and female horror anthologies like Rachele Wiggins’ Deadhouse Dark and Megan Riakos’ Dark Whispers.

Thankfully I have a great board of directors at the ADG: Rowan Woods, Daina Reid, Pearl Tan, Stephen Wallace, Nadia Tass, Anna Broinowski and Jonathan Brough have put in many hours of discussion and deliberation about policy and strategy – and the last year with Executive Director Diana Burnett has been incredible in terms of membership uptake and diversity.

The ADG Awards are being held online on 19 October. What can you tell us about them and how are they special this year?

They are a celebration of the skill and talent of directors. It’s a great moment to take stock of the immense work that is created by Australian directors each year across so many different platforms. I am always amazed by how much actually gets made (mostly on the smell of an oily rag) and how much passion and ingenuity we have in our directing community.

As one of the founding members of the Gender Matters taskforce, what do you see as the main impediments to making progress for women and other under-represented groups?

The main impediments to progress in equal representation are similar in our industry as they are in others. We only have to look at Ruth Bader Ginsburg to see that. Those who hold power, and are gatekeepers, are mostly reluctant to cede their power. That said, economics and data help a little. There are now vast audiences for stories made by, and about women – and the gatekeepers who are fastest to acknowledge that fact will be the most rewarded. Look at Elisabeth Murdoch’s investment in Sister Pictures – a UK- and US-based production company with formidable executives like Stacey Snider and Jane Featherstone who are committed to producing female led content.

‘There are now vast audiences for stories made by, and about women – and the gatekeepers who are fastest to acknowledge that fact will be the most rewarded.’

During your time at AFTRS, was there any advice you found yourself having to give constantly?

Know yourself and know your audience. Be Bold. Be Real. Be Rigorous.

There is a perception that it’s particularly difficult to combine the hours and intensity of a directing career and also being a parent of young children, or even teenagers. Do you have any thoughts on how this could be better navigated personally and within the industry at large?

As a young woman I found it relatively straightforward to navigate the pathway to becoming a director – I worked tirelessly, I was driven by an intense love of cinema, I was happier directing than in my daily life. Once I became a mother of two daughters, and a single mother for a significant portion of that time, I found it much more difficult to juggle the exigencies of a directing career with my desire to stay close to my girls.

Listening to the Polly Platt episodes on the podcast series ‘You Must Remember This’, I heard lots of relatable anecdotes that paralleled some of my own experiences fifty years later. That said, if it were not for women like Polly Platt, Gillian Armstrong, Sally Potter, Jocelyn Moorhouse and Jane Campion, as well as producers Sandra Levy and Bridget Ikin, it’s unlikely I would have had the early opportunities that I enjoyed as a young woman director.

I’ve also learned to share my experience as a working mother with my crew. Most men on set – whether grips, gaffers, assistant directors, camera and lighting crew, production design – have children. They too, want to get home to see their kids before bedtime or in the morning. I’ve definitely bonded with crew members over sharing our affection for our families, and that has sometimes enhanced our working relationships.

Beyond my personal experience, there are many examples close by of Australian women directors who are adroitly balancing their directing careers and their parenting – contemporaries such as Daina Reid, Kate Dennis, Jennifer Peedom, Rachel Perkins, Rachel Griffiths, Catriona McKenzie, Clare McCarthy as well as former AFTRS students of mine who have made their debuts in directing and have had children at the same time. Shannon Murphy, Jen Leacy, Lucy Gaffy, Martha Goddard and Miranda Nation are examples of this. That’s not to say that its not a juggle for all of them, but now that women’s experiences as working mothers are more readily acknowledged, structures to support them can be tangibly envisaged. Filmmaker and Women’s advocate/activist, Megan Riakos has done extraordinary work through Women in Film & TV (WIFT) to bring the issues surrounding working mothers in the industry to light.

Pet peeves? What annoys or troubles you?

Life is full of change and, frankly, it’s short, so it’s essential to focus on what’s possible, to look for the gaps and opportunities rather than spend too much time on what’s not working. That’s not to say reflection and advocacy aren’t essential also – we would lose some hard won ground without them.

‘Progress for women and other underrepresented groups is more likely to be achieved if we, individually, disavow ourselves of the notion that if we are “personally” successful then the paradigm has shifted.’

But last year at a conference for diversity in cinema, I heard a female director, now working in Hollywood, express her thoughts about having ‘survivor guilt’ at being on of the few women to get through the system to direct a big budget film. At the time this snagged with me but I wasn’t certain why, as I have immense respect for that director. When I read your question I thought about that feeling again and realised that progress for women and other underrepresented groups is more likely to be achieved if we, individually, disavow ourselves of the notion that if we are ‘personally’ successful then the paradigm has shifted.

Deanne Weir expressed it succinctly when she said in an International Women’s Development Agency speech in 2018 that a feminist leader can be a man or a woman, for they are not embodied only by a woman who is successful, but by a person who also seeks to shift the status quo for the underrepresented.

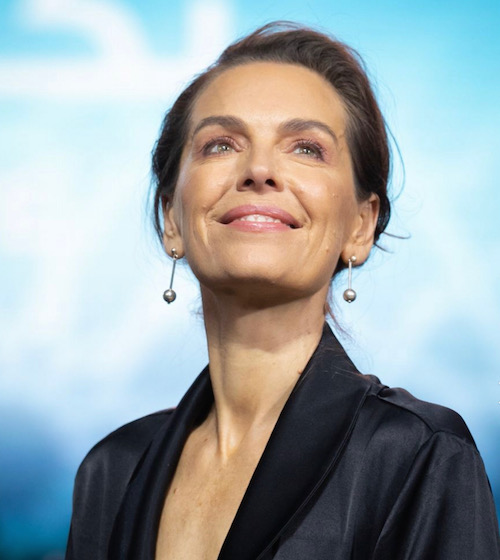

Sam Lang at the Marrakech Film Festival in 2019. Photo by Romuald Meigneux.

Postscript: In corresponding with Lang and asking for photos of her at work, she sent this one above, and included the following comment, which leaves us on a sobering note that will resonate with anyone involved in the Australian Arts in this political moment:

‘Having talked about one of my career highpoints being The Well and being in competition in Cannes, I thought it was relevant to mention that in Dec 2019, 22 years later, a delegation of filmmakers and actors were invited by the Prince of Marrakech to attend the Marrakech Film Festival where there was a week long tribute to Australian Cinema. Australian films shown at the festival, included The Well, but more importantly films like Mad Max, Bran Nue Dae, Babyteeth and Balibo. The event culminated in an onstage finale with many of the Australian attendees. Presented by Tilda Swinton, there was a 10-minute assembly of Australian films across the last 90 years. Jack Thompson, Gillian Armstrong, Jan Chapman, Rolf de Heer, Simon Baker, David Michôd, Mirrah Foulkes and Rachel Perkins were amongst the group. It was an incredible moment of celebration of Australian cinema and its creative voices. The photo (above) was taken while I was on stage. The following morning we all came to breakfast and heard that back in Australia, the Ministry for the Arts had been dissolved into the Ministry for Roads and Transport….’

This interview was assisted by Dame Changer, an Australian professional women’s collective, providing opportunities in training and networking for women in the screen industry, and The Power of Visibility. For more on Samantha Lang visit her website.