In a first for Australia, the South Australian government has announced a new rebate for video game development. Companies will be able to recoup 10% of production costs on projects spending at least A$250,000 in the state.

This rebate is a strong step for the local industry, but more than one approach is needed to make games production sustainable in Australia. This funding has the potential to grow mid-to-large sized game development teams, but not the smaller creators.

While a handful of Australian studios have teams of 20-50 staff and a couple of foreign-owned companies can boast workforces of approximately 150, the video game industry here is overwhelmingly populated by much smaller, independent teams.

These groups of 10 or less, located in co-working spaces or single-room offices, rely overwhelmingly on casual or contract employment, often creating just one or two games.

An industry of small players

Australia’s small indie teams, though volatile, have had a number of hugely creative global successes over the past decade, such as Untitled Goose Game and Hollow Knight.

Historically, support for independent development in Australia has been sporadic and inconsistent, largely funded through state-based grant programs offering relatively small amounts of cash to cover production expenses, travel costs and skills development.

Read: Social games to play while you wait for multiplayer ‘Untitled Goose Game’

While some Australian game-makers have dreams of growing into huge companies, many want to continue making games at the size they are. Imagine an indie rock band with a breakout hit – they’re not about to go and employ 100 more drummers. But this creates a problem for the local industry.

The Game Development Association of Australia estimates every year, 5,000 students enrol in tertiary game development programs. In an industry where most teams are content to stay at the same (small) size, these students have nowhere to go and no choice but to start their own independent companies.

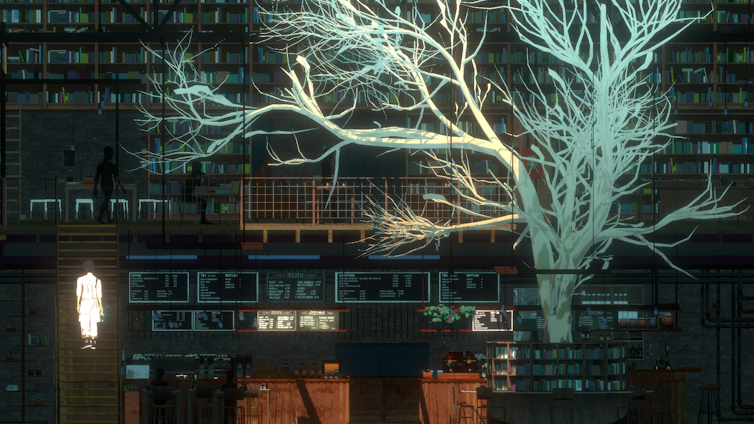

Some will have massive breakout hits – like Route 59 with their recent game Necrobarista. Many will release their first game to no fanfare. Their company will fold and they will disappear into other sectors or head overseas.

Plenty of (risky) room to grow

Mid and late career overseas talent won’t move to Australia without opportunities for later career employment. This leads to a senior talent vacuum.

Rebates can help here, encouraging large multinational companies, such as Rockstar, Activision and Ubisoft, to set up or invest in studios in countries where they can access the most skilled developers at the cheapest cost.

This is something that Canada, in particular Montreal, has taken advantage of. Since the late 1990s, the Canadian and Quebecois governments have offered the industry a range of subsidies, rebates and tax offsets.

Montreal alone is now home to over 10,000 game developers (10 times more than all of Australia); 3,000 at the local Ubisoft studio alone.

But there’s also risk in growing a local game industry this way. When Quebec tried to remove its tax breaks in 2014, the local industry threatened to head elsewhere. The government reinstated the tax breaks the following year.

Australia has seen a similar story before. In the late 2000s, Australian studios were largely dependent on contract work and financial arrangements with North American publishers. When the Australian and American dollars hit parity during the Global Financial Crisis, Australia could no longer provide cheap outsourced labour. Studio closures came hard and fast – all but decimating the Australian video game industry at the time.

Read: How Film Victoria funds games

With the new rebate, South Australia is hoping to attract some of these overseas businesses to take advantage of local talent. There’s always the risk somewhere else will eventually offer an even better rebate.

Nonetheless, attracting international companies to the state would give graduates a chance to be employed at a larger, more stable company and develop their skills before going indie later in their career, with more experience.

A multi-pronged approach

The rebate is also primed to benefit the few mid-sized South Australian studios that already exist, such as Mighty Kingdom and Monkeystack, and encourage other smaller teams to consider scaling up.

But such a rebate is less useful to the small independent teams that are currently the bread and butter of the Australian industry, many of which don’t have $250,000 to invest in a project.

For these small teams, producing innovative intellectual property exported across the world, grant programs are more immediately useful.

Building a sustainable and successful video game industry requires a multi-pronged approach that nurtures the whole ecology: creatively driven artists that are the local talent, business-savvy entrepreneurial start-ups with the ambition to build larger Australian owned studios, and the massive (but fickle) foreign owned studios that provide little creative freedom but much greater employment stability and opportunity.

The SA rebate alone won’t create a sustainable national industry, but in lieu of much needed support from the Federal Government it is another step in the right direction by a state government.![]()

Brendan Keogh, ARC DECRA Fellow, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.