By Lisa M. Given, RMIT University; Jessica Balanzategui, RMIT University, and Sarah Polkinghorne, RMIT University

As artificial intelligence becomes mainstream, its infiltration into children’s lives is causing tremendous anxiety. The global panic around AI’s co-option of children’s play and cultures has manifested unpredictably.

Earlier this year, a Swiss comedian created a film trailer for an imagined remake of the beloved children’s story Heidi using the AI tool Gen-2.

Heidi’s more than 25 film and television retellings (including the most famous 1937 version starring Shirley Temple) are key to cultural archetypes of childhood innocence. The viral AI-generated version sparked headlines for being a godless abyss, nightmare fuel and absolutely soulless and detached from humanity.

This isn’t the first time AI has been used to re-imagine representations of childhood through the creation of cultural artefacts. Researchers trained a deep learning algorithm using children’s books by Dr Seuss, Maurice Sendak and others, with the resulting storybook images described as an apocalyptic nightmare and visions from hell.

When a technology worker used ChatGPT and Midjourney to create a children’s book, he received death threats.

M3GAN and AI dolls

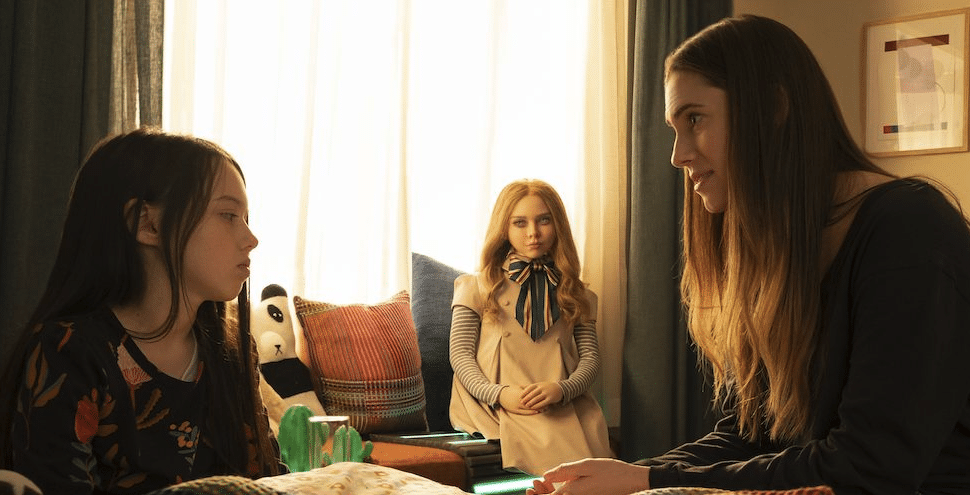

One of the most successful horror films of 2022, M3GAN, depicts the disturbing results of a grieving girl’s friendship with an ultra-lifelike AI-powered doll.

A clip of M3GAN dancing (her face expressionless as her body emulates moves from youth dance trends on social media) went viral to an extent the director called ‘unbelievable‘. M3GAN strikes a cultural chord, embodying our discomfort with how AI co-opts and twists children’s culture.

The Artifice Girl (2022) depicts an AI-generated nine-year-old designed to lure predators online, highlighting debates about AI ethics. Reviewer Sheila O’Malley compared this to Blade Runner (1982), asking:

If a memory is implanted into an android’s brain, a ‘personal’ memory of a childhood that never happened, then isn’t that memory a real thing to the android? The android can’t tell the difference. It feels real. At a certain point, what is or is not ‘real’ is irrelevant. This is when things get unsettling, and The Artifice Girl sits in that very unsettling place.

AI tools sit uncomfortably with our imaginings of childhood. The constellation of play, games, stories and toys that constitutes children’s social worlds is symbolic of innocence, naivety and freedom from the darkest burdens of adult life.

Childhood studies link mythologies of freedom and innocence to faith in humanity. When AI tools pervert children’s culture, they spark our deepest fears about AI’s inhuman modes of intelligence.

AI’s ability to mimic human creators, while hallucinating and twisting reality, gives us reason to worry.

The long history of childhood techno-phobia

Cultural anxieties about AI’s infiltration of children’s culture continue a long history of pop cultural preoccupations with dangerous interactions between children and technologies that cannot be trusted.

With Poltergeist (1982), the world was enthralled by five-year-old Carol Anne’s haunting statement, ‘They’re here …’ She was listening to poltergeists through the family’s television.

This resonated with parents concerned with children’s screen time, as well as video games, Dungeons and Dragons and Satanic ritual abuse. Carol Anne’s television fixation reflects the terrifying potential of technology to unsettle family life.

Mary Shelley’s 1818 classic Frankenstein, like M3GAN, depicts a young girl dangerously entranced by embodied technology. In its 1931 film adaptation, we see Frankenstein’s monster meeting seven-year-old Maria, who overcomes her initial shock, asks him to play and meets an untimely end.

Come Play (2020) depicts young Oliver who befriends a monster through an app, with deadly screen-time results. Where Poltergeist imagines consequences from too much television, Come Play echoes parents’ fears of losing their children to smartphones and gaming, such as Minecraft.

AI is a lightning rod for fear

M3GAN’s embodied AI reflects the current wave of concern. In May, AI companies made headlines when they linked AI to potential human extinction. While experts dismissed these claims, perceptions of AI as a significant threat echoes the horrors of AI depicted in film.

One example is 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), in which HAL 9000 takes control of the spaceship to protect the mission. Many other films depict out-of-control AI, including WestWorld (1973), Tron (1982), Terminator (1984), The Matrix (1999), I.Robot (2004), Moon (2009), Ex Machina (2014) and Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015). These films resonate today, as AI seems poised to replace human workers.

The idea we can create autonomous technologies that may eradicate humanity prompts what researchers call ‘moral panic’. This is contagious fear, amplified by the media, and fixated on looming threats to social stability. New media often give voice to youth, challenging norms and exacerbating generational divides, further contributing to recurring moral panics.

While filmmakers highlight AI’s potential threats, today’s tools struggle to generate coherent knitting patterns or recipes that aren’t poisonous. AI’s real threats to children include its ability to present misinformation in convincing ways and replicate social biases. The climate change impacts of AI are troubling, as is the lack of transparency and privacy concerns.

While we shouldn’t be swept up by moral panics, children’s use and understanding of AI should be addressed. UNICEF is embedding children’s rights into global AI policy and the World Economic Forum has released an AI for children toolkit.

While horror stories shed light on our anxieties about children’s technology use, and our imaginings of children’s play and culture, we don’t need to recoil in fear.

Lisa M. Given, Professor of Information Sciences & Director, Social Change Enabling Impact Platform, RMIT University; Jessica Balanzategui, Senior Lecturer in Media, RMIT University, and Sarah Polkinghorne, Research Fellow, Social Change, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.