Since the advent of the Internet some twenty years ago, users have experimented with a wide host of browsers and programs in their quest for digital best. With a constant cycle of updates and replacements, the original online frontier grows more and more distant.

Yet as we move ahead, some of us are looking back in a bid to rediscover the classic face of computers and the Internet. Flying Toasters, the turning wheel of Netscape Navigator and other symbols of a time gone past are emerging in digital collage, textile design, video artwork and even puppetry.

But is it all too soon?

A sped up sense of nostalgia

As artists explore the tumultuous history of the digital and create nostalgic works, some of us are questioning whether this resurgence is slightly premature. The phrase back in my day is usually followed by a spirited ramble of times when things cost a penny and milk was delivered to the door, not of when people used to ICQ each other and surf around with HotBot.

On the surface, nostalgic sentiments spanning back to the cusp of the millennium may seem pre-emptive … until the wider context of online culture is understood.

Mary Rachel Kostreva of Tight Artists HTML gallery believes that online cycles are accelerated in comparison to real world cycles. Browsers rise and fall, versions are superseded in mere heartbeats and universally adopted programs can disappear after just a few months.

According to Kostreva a true sense of nostalgia can build up around this fast turn around of programs and systems. ‘I think/hope that there is always a certain level of sincerity to it, considering that most of us millennials grew up using the Internet and have fond memories of what it once was (and miss it to a certain extent).’

Her Tight Artists partner Adam Bech Harms agrees. ‘Even though we may lose interest in a site, program, forum, etcetera, we were still highly engaged with it at one time. We have fond memories when it was at the height of our interest, when it “was still good.” Those are the memories that become romanticised and sentimental. The cycle of generating nostalgia mirrors the life-span of these online entities.’

An extra sense of loss stems from the common user belief that the Internet is permanent. Digital artist KT Spit and others have found out over time that this is a fallacy. ‘We (especially women as a warning not to “overshare” ourselves) are constantly reminded that what’s online is forever, that the ‘net itself is an eternal/timeless but expanding entity and cannot decay. But actually it ages rapidly and often if you go find your history its not ‘active’ anymore,’ said Spit.

As programs, access and content disappear, real feelings of emptiness emerge.

‘These are places, formats in which we have existed, and we have learnt, loved, LIVED online, and now so much of it is actually gone. It all went by so fast,’ said Spit.

A sincere representation

LA-based artist Christina Bercovitz is an inter-disciplinary artist and puppeteer who has incorporated classic Internet symbols in her creations. For Bercovitz, her experimentation with the forms and images of an early Internet, as in this handbag, is simply a way of adding more colours to the palette.

‘As the novelty of the new wears off, many people including myself are changing attitudes towards the new and old and instead of judging them as superior and obsolete we are seeing these technologies simply as different tools. A painter can choose from a variety of materials and techniques that have different aesthetics such as choosing to use oil or watercolour to create their art. A video artist can similarly choose between the different aesthetics of DSLR or Betamax.’

Bercovitz believes that newer doesn’t always equal better, with many old technologies able to inform upon modern practice.

‘I don’t think it is nostalgia alone that is driving this love of old technology. I might have fond memories of Super Mario Kart but that doesn’t mean it’s not still awesome.’

Her approach is genuine. For Bercovitz the adoption of early Internet and computer imagery is simply a way to move artistically forward with as many options as possible.

A conflict of irony

Despite a sincere feeling towards the computer culture of old, many works that incorporate its classic motifs can come across as ironic. According to Bech Harms, it takes more than a random collage of icons to achieve a work of art that is sufficiently engaging and evokes aesthetic response.

‘Nostalgia is really about the feeling the memories give you so I find it’s most successful when artists try and capture that feeling in the style of their work. Personally when I see Internet nostalgia used as subject matter I find the work to be flat and uninteresting. Nostalgia goes against critical thinking, it glorifies.’

There are, however, artists who are purposefully cynical. Max Schreier, curator and associate director at DUVE Berlin is quick to label this approach as ultimately unfulfilling. ‘Why should an audience spend time thoughtfully considering a work if it comes from a cynical or ironic place? As an artist why would you present something that you inherently find tacky, low quality, or just bad and put it forward as a work without making a sincere effort to place it in a meaningful cultural position?’

Yet some artworks seem to be both sincere and ironic at the same time. While this initially seems impossible, the sped up conditions in which Internet nostalgia emerged has helped to make this an actuality.

According to Schreier, ‘As the rate of technological development exponentially speeds up, the distance needed from a certain event or technology to be nostalgic decreases. With that said that does not give us much time to consider the value of the things we become nostalgic for.’

This can culminate in a nostalgic feeling that has confused or conflicting values. As images are engaged with in a heartfelt and idealistic manner they are at the same time iconified and enmeshed into a culture that subverts their original meanings and exposes the promises they failed to deliver on.

This oscillation between both the sincere and the ironic is a valid and modern understanding, and one that is informing much post-Internet work.

A metamodern understanding

In an attempt to address this dual understanding, the cultural paradigm of metamodernism can be considered. Metamodernism moves beyond the previous scepticism of post-modernity to explain the contemporary world that has emerged from networked culture. Modernist ideals of hope and freedom are also acknowledged, distinguishing the paradigm from post-post-modernism.

According to Dr Hila Shachar, Honorary Research Fellow in English and Cultural Studies at The University of Western Australia and co-editor of Notes on Metamodernism, ‘What we’re witnessing now is a much more “knowing” and self-aware re-engagement with past traditions that takes into account the legacies of postmodernism.’

Metamodernism moves between skepticism and authenticity as a way to summarise the conflicted responses many feel towards the current world.

Shachar’s co-editor, Luke Turner, believes that network culture is an area of conflict. ‘These new technologies have begun to bring about societal change, with technology able to collapse outmoded hierarchies of knowledge, and a new dawn of collaborative endeavour signaled by the commons and open-source culture. At the same time, with new monopolies being built and government surveillance seemingly out of control, the implications of technology on our civil liberties appear ominous.’

By existing within this digital culture a swinging oscillation between hope and despair is intuitively assumed. Internet nostalgia relates to this by highlighting a recent past that is now obsolete through swift technological advancement.

‘Given the frustrations of current times, there is a very palpable sense of nostalgia for the unfulfilled promises of past utopian visions. In revisiting these moments, as we oscillate between former and future visions, there is perhaps a hope that we might come to realise something anew, and fulfil that elusive utopian dream.’

There is also a keen understanding that these past promises led to nothing, adding a concurrent feeling of doom and mistrust.

While Turner and Shachar both believe there is a huge amount of banal post-Internet artwork that doesn’t move beyond the post-modern sense of irony, they also recognise a vast amount of innovation and inspiration online that reflects a more complex understanding.

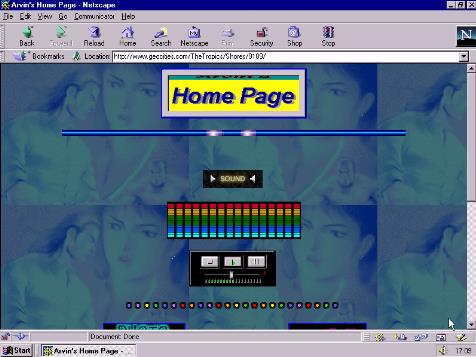

Curator Schreier uses Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied’s One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age (below) as an example of work that addresses specific visual tropes of classic Internet. ‘It is a beautiful archive of old geocities pages, that does a wonderful job of creating a comprehensive and non-judgmental survey of some of the first easily accessible HTML coding, and what people were able to do with a website in the late 1990s and early 2000s,’ said Schreier. While Lialina and Espenschied’s work is sincere, there is also a sense of conflict related to values of the subject matter that is inherently metamodern.

Constant Dullaart is another artist Schreier recommends, whose iconography is so well researched the viewer may not recognise it is from another time at all. Dullaart’s work incorporates authenticity and paranoia in what could also be considered a metamodern approach.

Whether examples of work with increasingly transparent metamodern values will arise over time is a complex question. As the Internet keeps growing and updating in exponential degrees a wide range of creative practices may emerge from different philosophical paradigms to deal with the emergent culture. Predicting how this will impact upon creative practice is a challenging task.

Hmmm, perhaps we should ask Jeeves.