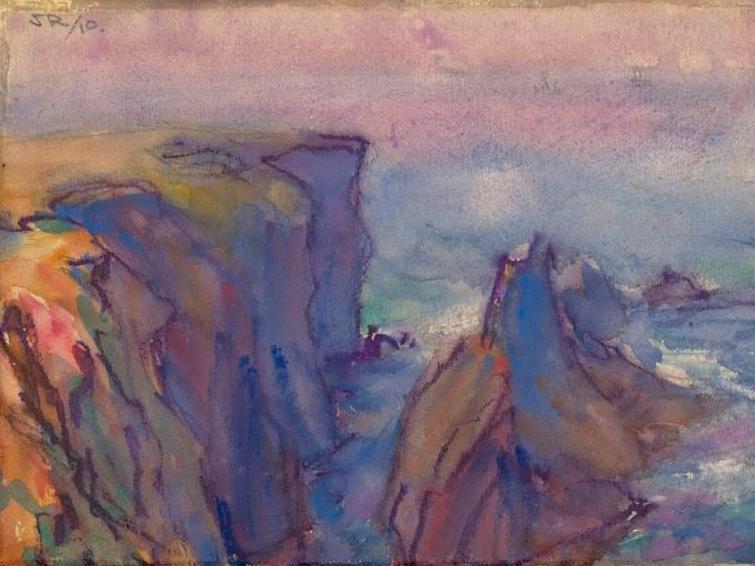

Les Aiguilles, Belle Ile (detail) (1910). Watercolour: pencil, watercolour, gouache, scraping out on off-white wove paper. John Russell, 16 Jun 1858 – 22 Apr 1930. Art Gallery of NSW.

Australia’s Lost Impressionist – John Russell (2017) is an enamoured documentary reminiscing on the life of an artist that time forgot, and proposing he is remembered with national esteem.

While born in Australia, John Russell (1858-1930) was among the first of Australian artists to train in Europe during early adulthood and enjoyed an extended stay in rural France. Consequently, his contribution to the impressionist movement is absent from the Australian consciousness.

A century on, director Catherine Hunter flexes her experience of covering Australian visual arts to chronicle his life and garner his recognition. Between nostalgic historical documentation, romantic landscapes shots (owing to cinematographer Bruce Inglis) and enthusiastic interviews, Russell’s voice is elegantly portrayed. Yet, the aim to construct his public face is ajar with this intimate approach and, even, with Russell’s values.

Through a linear progression, Hunter depicts Russell as a significant impressionist with an amiable disposition. Just short of an hour and framed by mentions of his early and late Australian life, the film reflects the impact of his European education, relationships with prevalent artists, whirlwind romance with his wife and muse Marianna Antonietta Mattiocco (1865-1908) and intensely spiritual connection to the landscape of Belle-Île’, France.

At capacity with appealing visuals and animated dialogue, the film emphasises picturesque rural France, Russell’s personal letters (voiced by Hugo Weaving) and contextualising contemporary interviews. Overall, Russell is honoured by Hunter’s romanticised overview of his overtly personal practice.

The chronological narrative shifts between archival and contemporary perspectives, the strength being the latter. The cohesive incorporation of Weaving’s sincere voicing of Russell’s poetic letters exchanged with the likes of Monet, Matisse, Van Gogh and Rodin and Inglis’ camerawork highlighting Russell’s complexity of colour, energy, texture and form establish the extensive influence of his intimate friendships. The letters are poignant to the extent that any trauma experienced within his relationships are pivotal and emotional plot points. As the documentary integrates historical documentation centralised on his personal life, Russell’s essence is magnetic.

These techniques contrast to contemporary angles, which include flaunting the forceful coast of Belle-Île’ and a bulk of the dialogue dedicated to flattering scholarly interviews and visceral perspectives from Russell’s descendants, artists and locals of Belle-Île’. While expressively conveying his passion to his wife, friends and home, the lack of critique to complement the sentimentally framed historical documentation makes for an overly wistful grasp at Russell’s present-day relevance.

By offering an intensely-personal portrayal of Russell, the film’s purpose of creating a public icon is misdirected. Perhaps, Hunter appropriately compels audiences to see Australia’s impact in significant art movements as the nation continues to struggle with ‘cultural cringe’ and flocks to visiting blockbuster impressionist exhibitions, like the recent Van Gogh and the Seasons at the National Gallery of Victoria.

However, the optimist approach to uphold this forgotten Australian impressionist is at times overplayed. The narrative implies while Russell’s innovative practice significantly influenced the artistic development of many notable artists, he didn’t warrant a similar iconic status. His minimal recognition is commiserated through a bittersweet moment when an almost pitiful memorial is located at his late-Australian home, incongruous with the preceding powerful rendition of Russell’s musings on nature assembled with the striking French landscape.

Pushing Russell into the spotlight causes various curators and authors to speculate on his aspirations to justify their promotion. A brief comment on the subjective nature of success not followed up, despite its potential to question Russell’s desire for public acclaim.

Following a mastered depiction of Russell maturing as an artist in his own space and relationships, rather than through success in the public sphere, it feels discordant to ask for a new outcome of his career.

With poeticism, the documentary augments Russell’s spirit. Instead of determinedly placing him on a pedestal, the romantic portrayal could have been effectively leveraged as a retrospective impressionist memoir and celebration of Australian talent. By accentuating his artistic ingenuity through his private life, it is amiss to not also examine his ambition for success.

While the film cannot garner widespread acclaim, its enthusiastic and nostalgic presentation plants promising grassroots in his honour. An excitable, albeit noncritical, glimpse into the life of little-known Russell, the film effectively introduces and sparks fresh endearment of an exceptional impressionist and person.

Rating: 3 ½ stars ★★★☆

Australia’s Lost Impressionist – John Russell

Director: Catherine Hunter

Australia, 2018, 58 mins

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: