Jessica Balanzategui, RMIT University

The past decade has been a golden one for Australian horror, bookended by The Babadook in 2014 and the current sensation Talk to Me.

The global premiere of Jennifer Kent’s groundbreaking supernatural bogeyman film at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival caused ripples that became a wave.

The Babadook attracted international acclaim, winning the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best First Feature. The Exorcist’s director, William Friedkin, called it the most terrifying film he’d ever seen.

Talk to Me, the directorial feature debut of brothers Danny and Michael Philippou, also premiered internationally at Sundance, where it sparked a bidding war.

Read: Our interview with the Philippous

Now in cinemas, Talk to Me has surpassed industry projections to gross more than US$10 million (A$15.2 million) in North America on its opening weekend, and opened at number four in Australia. Talk to Me’s success story is not just commercial but critical: the film currently has a 94% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

This horror high water mark carries the legacy of Australia’s strong horror history, while signalling the shedding of some cultural biases that have constrained our culture of innovation in spookery.

The Australian New Wave

Australia’s golden horror decade has roots in the Australian New Wave, a particularly productive period for Australian film from the 1970s to the late 1980s dominated by two key horror subgenres on opposing ends of the taste spectrum.

The high-brow Australian Gothic includes critically esteemed dramas Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) and Walkabout (1971). These films are structured by enigmatic narratives with horror-tinged edges, in which the ethereal beauty of the bush also bears quasi-supernatural menace.

Low-brow Ozploitation films were popular in drive-in theatres, but often critically derided for their ‘tasteless’ violence and sex and for cribbing flagrantly from Hollywood horror.

Classics of the genre include Razorback (1984), pitched as ‘Jaws on trotters’ (the film features a murderous bush hog), and Patrick (1978), about a man in a coma with psychokinetic (and psychosexual) powers.

Ozploitation is often seen as the rebelliously gory, commercially oriented antagonist to the Australian Gothic’s highbrow works of art.

Destroying the high/low culture binary

This binary persisted into the early 21st century. The international commercial success of homegrown horror hits such as Saw (2004) and Wolf Creek (2005) was often accompanied by domestic critical derision: Margaret Pomeranz and David Stratton refused to review Wolf Creek 2 (2013).

The horror films of the past decade tend to trample over this high/low genre binary.

These films experiment with art cinema aesthetics and deploy narrative strategies of prestige drama, echoing the Australian Gothic. However the supernatural elements are an explicit narrative structuring device, unashamedly emphasising their horror identities.

The ghosts and bogeymen of films like The Babadook, Relic (2020) and Talk to Me provoke shock and disgust, while also poetically expressing psychological turmoils that evade coherent explanation.

Read: Talk to Me reviewed

In The Babadook, this turmoil erupts from shared grief between mother and son. In Natalie Erika James’ debut feature Relic, a grandmother’s descent into dementia impels the reverberation of spectral traumas across three generations. In Talk to Me, a blossoming teen friendship is possessed by the unquiet spirit of the protagonist’s dead mother.

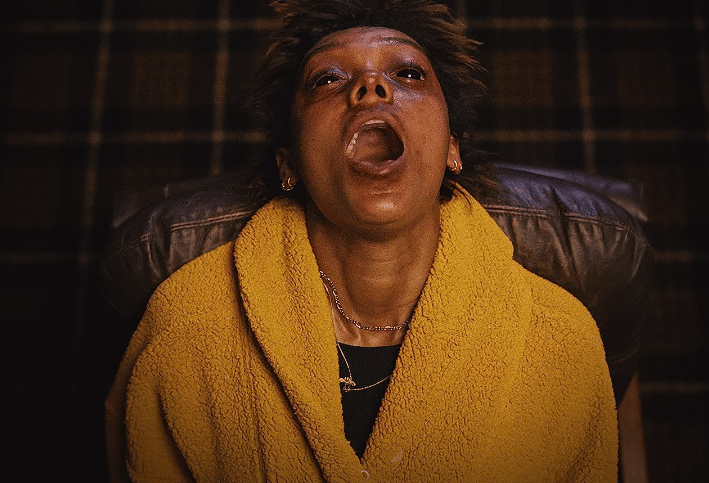

Alongside this nuanced dramatic core, Talk To Me pushes the boundaries of good taste with gleeful abandon in true Ozploitation style. It features gruesome possession-induced self-harm and more than 100 swear words. The narrative centres on a darkly comic analogy (instead of drug-taking, the teens become addicted to the occult pleasures of the talismanic hand) that would be at home in a grindhouse drive-in.

This play with high/low culture boundaries filters into Talk To Me’s play with audience emotions and expectations.

At times while watching, my body was tensely primed for a gory eye-gouging; instead I was met with a gentle moment of connection between two characters. At other moments, tender sequences give way unexpectedly to viscous spurts of blood.

The ghouls of this golden decade are at home on the red carpets of festivals such as Sundance, yet they also drip with the blood and bodily fluids of their Ozploitation forebears.

A collective energy

Our current golden age of horror has grown out of a collective creative energy.

The Philippou brothers worked on The Babadook as 19-year-olds and credit Kent’s influence as key to their creative approach.

The Babadook was the debut film from Australian production company Causeway Films, and Talk To Me is their latest picture, led by producer Samantha Jennings.

Jennings and Causeway have been critical to the collective currents that have propelled our golden horror decade. They also produced the conceptually layered zombie horror-drama Cargo (2017) and witch folk horror You Won’t Be Alone (2021), Australia’s submission for the Academy Awards for Best International Feature.

This decade of ingenuity has demonstrated Australian horror films can find international success blending the highbrow and lowbrow, yet the constraining thinking of the New Wave-era continues to haunt the local screen sector.

Kent’s The Babadook received a limited release on only 13 screens in Australia after being deemed too ‘art-house’. James’ internationally acclaimed Relic was not screened theatrically on home soil until three years after its Sundance premiere (a screening I co-organised with ACMI). You Won’t Be Alone might have been Australia’s Oscars submission, but it did not receive a single nomination at our local AACTA Awards.

The last decade has showcased that Australian horror can be worthy of domestic and critical attention and a gory good time with commercial appeal. Perhaps the success of Talk to Me both at the box office and with critics will encourage us to listen.![]()

Jessica Balanzategui, Senior Lecturer in Media, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.