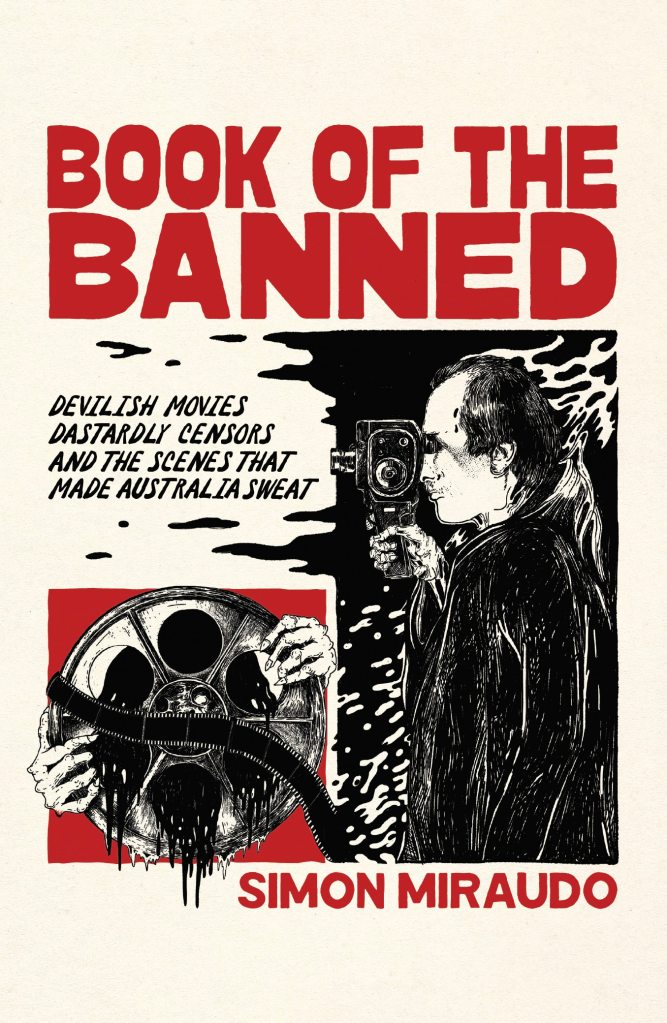

This is an edited extract from Book of the Banned: Devilish Movies, Dastardly Censors and the Scenes That Made Australia Sweat, by Simon Miraudo.

Australia undeniably needs a classification system for media, primarily to ensure young people aren’t harmed in the production of or by the unfettered consumption of violent, degrading or sexually abusive content. But in our attempt to walk that fine line between artistic freedom and consumer protection, Australia – and its federal and state-based arms of classification – has often waddled clumsily, usually overcorrecting to the point of absurdity.

And we’re not just talking about the censorship of pornography here. We’ve proven ourselves to be quite adept at falling face-first in our attempts to halt more traditional works, too. It’s ominous enough when police are instructed to raid cinemas, confiscate DVDs or halt theatrical productions in the name of state-sanctioned censorship, wherever in the world that may be taking place.

In Australia, however, the censorship of film and art often ends up a surreal spectacle, with police storming the stage to arrest beloved TV personality Margaret Pomeranz, or, in a particularly Brechtian instance, some literal puppets.

Censorship overseas

Of course, other nations have their own censorious histories. From 1934 to 1968 Hollywood had the Hays Code, which tried to stem the damage of its Golden Era scandals by keeping smut and violence off the screen, necessitating the introduction of sly visual language. (Think: a train entering a tunnel to symbolise sex; a classic of the genre!) The British parliament passed the Video Recordings Act 1984 at the behest of conservative family groups to limit violent ‘video nasties’ from going direct-to-VHS.

China and Russia have scrubbed gay and lesbian content from many international imports. And the Monty Python crew faced global ire with its provocative 1979 satire Life of Brian, though Sweden saw the light side of the situation, using the fact it was banned as Norway on advertisements to stir some local pride in contrast with their neighbouring prudes.

Australia never banned Life of Brian, and we didn’t cut any queer content from Rocketman, Bohemian Rhapsody or Beauty and the Beast, as occurred elsewhere in the world. In the instance of Disney’s live-action remake of Beauty and the Beast, Kuwaiti censors were rankled by Josh Gad’s character, LeFou, and his longing looks at Gaston; mere seconds of screen time.

An Alabama drive-in similarly refused to screen this new take on an animated classic, explaining that they would not compromise on the teachings of the Bible, though I’m still not sure which Biblical book gives the thumbs up to the singing French candlestick. Australia even got the uncut version of David Lynch’s Wizard of Oz pastiche Wild at Heart in 1990, while Americans had to make do with a re-edit that obscures Willem Dafoe’s disgusting robber Bobby Peru accidentally blowing his own head off with a shotgun.

Still, we’re not yet as freewheeling as the French, who initially afforded their lascivious homegrown features Blue is the Warmest Colour and Double Lover a rating that allowed unaccompanied 12-year-olds into the cinema to see those films’ full-frontal escapades. Mon dieu!

Australia fair

Our nation self-identifies as fair and progressive, despite not having entrenched freedom of speech in our constitution. So we have to ask: what aren’t we allowed to see, and why? Who sets the rules? How harshly are they being enforced? Whose moral standards are being upheld, anyway? Who suffers as a result? And what compelled writer Robert Cettl, in his 2011 book Offensive to a Reasonable Adult, to declare that Australia’s classification system was ‘the strictest of all democratic nations in the western world’ – the same year we finally freed Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom from decades of censored solitary confinement?

My book specifically digs into the history of Australian cinematic censorship, revealing a series of surprising and sometimes shocking stories, often more memorable, disturbing, morally wrenching and darkly hilarious than the censored films themselves.

In each tale, there are heroes, anti-heroes, unexpected criminals and downright dastardly villains, though they’re not always whom you’d expect. Even the easily-blameable Classification Board, which has consistently shapeshifted over the decades and deserves closest scrutiny of all, offers a significant public service. In 2019 it reviewed and applied the Refused Classification (RC) rating to the Facebook livestream (or ‘short film’ as they described it) of Brenton Tarrant’s mass shooting at a Christchurch mosque, effectively banning it and introducing criminal penalties for those who try to share it. (According to Australian law at the time, no penalties could have been enforced until the board handed down the RC-rating.)

Public service?

The same public service cannot be claimed for past boards’ reactive ratings or straight-up censorship of classics La Dolce Vita, Blow-Up, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Rosemary’s Baby, Gimme Shelter, A Fistful of Dollars, The Graduate, Barbarella, The Birds, Salò, Breathless and, um, The Human Centipede 2, which all had their artistic merits challenged, and which all fought back against accusations of immorality with varying degrees of success.

In the case of 1960’s La Dolce Vita, it was a shot of a woman’s cleavage that was deleted from a strip act. In 1966’s Blow-Up, it was breasts and a flash of pubic hair in need of censoring, as well as some comparatively tame lines of dialogue (of the ‘get stuffed’ variety), which left the slashed sequences spluttering ‘like an old Charlie Chaplin comedy’, as was written in Cinema Papers.

By the end of the sixties, the board was cutting up to six minutes from the notorious Anthony Newley feature Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness? – though this was probably not Newley’s biggest problem at the time, given that his soon-to-be-ex Joan Collins later blamed the movie for their divorce.

The censors snipped 12 whole minutes from director Robert Rossen’s Lilith in 1964, including a lesbian sex scene featuring Jean Seberg’s nymphomaniac main character. Seberg probably wasn’t surprised, given Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 classic Breathless (À bout de souffle), in which she starred, was at this point still banned in Australia.

Godard was particularly unlucky here in the 1960s; the board censored nude footage of star Brigitte Bardot from his 1963 effort Contempt (Le Mépris); a year later they banned A Married Woman (Une femme mariée); and they banned Masculin Féminin in 1966 before passing a version with eight minutes deleted. Mercifully, Godard’s next feature, Week-end, would earn an uncut Australian release in 1971, soon after our introduction of the R-rating. That was still four years after it debuted in France.

It wasn’t just Godard who irked the censors. The entire filmmaking population of Sweden wound up in the crosshairs during the supposedly swinging sixties. Easily the most infamous Swedish export of the era was 1967’s I Am Curious (Yellow), which ignited a storm of controversy in the United States for its intersection of sociopolitical commentary and explicit sex.

If you’re worried how it fared in Australia, don’t: the distributors, aware of our reputation, didn’t even bother to attempt distribution until 1973. Even that was an ambitious swing at the time: a year earlier, the board had declared an RC-rating for Language of Love – submitted by the Swedish Institute of Sexual Research – before passing an edited version that came with a warning, as directed by the Attorney-General, that stressed it should only be considered for sex education purposes.

In 1953, it was written in The West Australian that ‘the average cut in a censored feature film is about ten feet’. They continued to make the point that, actually, we had it pretty good: ‘In 1952, a total of 650 feet were denied us from a total 3,103,696 feet, which constituted 390 feature films. We were denied 900 feet from 400 pictures in 1949, 1,040 feet from 407 pictures in 1950, and 860 feet from 427 films in 1951. These figures do not suggest our film censorship is heavy handed.’ Never mind that this meant nearly 36 minutes had been shorn unceremoniously over four years.

But the issue of censorship and inconsistent classification isn’t simply a dusty old scandal from the annals of Australian history.

Further examples of self-censorship can be found everywhere, if you know where to look (and my book will point you towards those filmic wounds), in movies ranging from Men in Black to Lady Bird – let alone the movies you’ll never see.

Means to an end

The censoring of films has always been a means to an end, and if films are more easily accessible now than ever before, Australia as a whole has become more censorious, secretive and invasive.

In May of 2022, Australia placed 39th on Reporters Without Borders’ (RSF) World Press Freedom Index, just behind the Ivory Coast and Taiwan. This ranking was the culmination of sweeping legislative actions by Scott Morrison’s Coalition government, including the regulation of our online spaces, which had been persistently tinkered with by preceding governments. Because of that, how we understand and legally define the concept of ‘harmful online content’ refers back to the National Classification Scheme.

Effectively, the way we are allowed to navigate the internet today is informed by a system that was designed decades ago to rate and censor-by-suggestion movies. This is a system that originated a century earlier for a totally different medium; an arm of censorship that was spurred by Sydney police who were sweating their depiction in bushranging flicks and Salvationists worried about sinners pashing on in darkened cinemas. Book of the Banned aims to connect these dots explicitly. As Ina Bertrand put it in her excoriating 1978 text Film Censorship in Australia:

If films were an esoteric commodity for a limited audience they would cause no more controversy than manuscripts did in the fourteenth century, before the invention of printing made possible cheap books. But films – like books –are a mass medium, so fear of their effects goes side by side with the spread of the technology that makes them possible. Out of fear grows the desire for control, a control which can –and does – take many forms.

The present day

Forty-five years later, this truth has crystallised.

As a film critic for the past 15 years – with more than 1,400 reviews contributed to Rotten Tomatoes – I’ve been particularly fascinated by cinematic exploits that have pushed boundaries and, specifically, censors’ noses out of joint. Some may chalk it up to an oh-so-Australian disdain for authority, or delighting in contrarianism.

But I truly believe discussing the movies, scenes, shots and individual lines of dialogue that were deemed too extreme for Aussie eyes and ears helps us see how far we’ve come in Australia as a society; and uncovering those that continue to send the wowsers to their fainting couches reminds us how far we have to go. To paraphrase John Waters’ Pink Flamingos – which was banned five times between 1976 and 1983 for ‘coprophagy’ among other things, and ultimately rated ‘X’ – I’m not shitting ya.

Simon Miraudo is a writer and film critic based in Perth, Western Australia. Book of the Banned: Devilish Movies, Dastardly Censors and the Scenes That Made Australia Sweat is available in stores from 1 August or from bookofthebanned.com.