Two men ride on horseback through a Medieval forest. We hear the older man telling the sceptical page that this lush evergreen forest must be inhabited by a unicorn – a creature thought to be extinct.

Rather than joyful, the man’s expression is haunted. As they leave, he turns back to the forest and addresses the unseen creature, with pity in his voice:

‘Stay where you are, core-beast! This is no world for you. Stay in your forest and keep your trees green and your friends protected. And good luck to you – for you are the last.’

The Unicorn is hidden among the trees, listening. ‘I’m the only unicorn there is? The last?’ Her voice is frail, scared, and disbelieving (a perfectly delivered performance by Mia Farrow). She walks aimlessly through the forest in confusion. It’s as if she’s woken up from a long sleep to discover that her sisters have vanished, and the world has moved on without her.

This is how we begin the adventure and slow-burn nightmare that is The Last Unicorn (1982).

When you think of unicorns, you probably picture happy fairytales about sparkly horses, princesses and magical kingdoms, or the national animal of Scotland. Hell, you might even expect some singing. I imagine that’s what my parents were picturing when I borrowed this VHS from Blockbuster almost every single weekend as a child. (Apologies to the owners of my local ‘BB’ – I was definitely singularly responsible for wearing that tape to a grainy, unviewable husk).

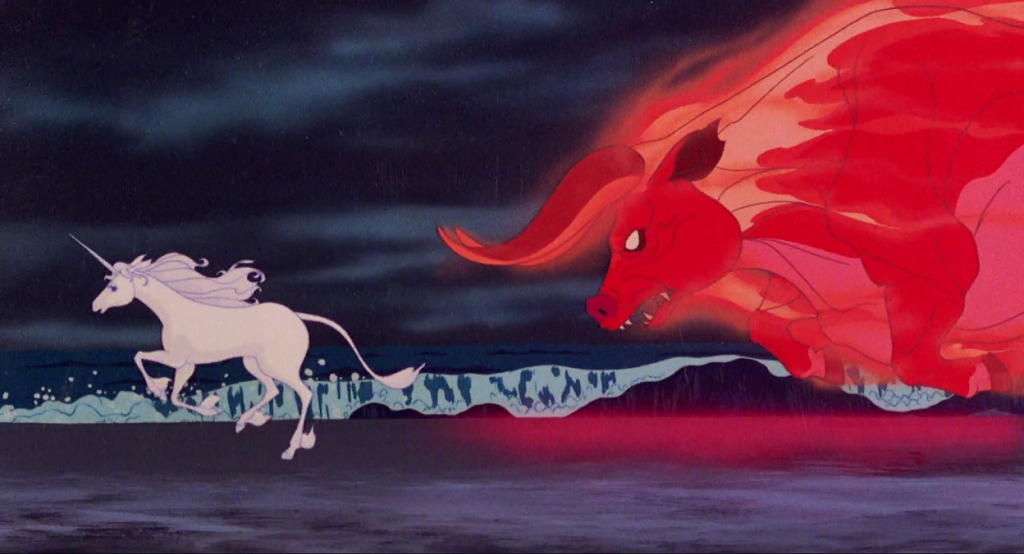

They (and I) wouldn’t have expected themes of imprisonment, mortality, isolation, and its resulting madness – not to mention a horrific and mutated bull that is permanently on fire, and regularly appears from vapour to haunt our protagonist.

Why does The Last Unicorn work?

Why has this film had such a lasting impact as a cult classic? Most people haven’t seen it, as it had a very limited release, but many of those who were exposed to it as children over the past four decades will eagerly tell you how brilliant it is. Occasionally, you will probably hear something along the lines of, ‘Huh – I thought that was something I invented in recurring nightmares. How about that.’

The Last Unicorn is a different breed of children’s movie, emerging from a less-financially viable, but more tonally adventurous point in animation history. It was the result of a unique collaboration between American production company Rankin/Bass (responsible for the similarly infamous Lord of the Rings animation of 1978) and the Japanese animation house Topcraft (the precursor to the beloved Studio Ghibli).

This collaboration between America/Japan results in a stunning animation style, seeing early anime technique influenced by Medieval iconography (see the famous Unicorn Tapestries of the 15th century).

Not to mention it has a stacked cast – Mia Farrow, Alan Arkin, Jeff Bridges, Angela Lansbury, and Christopher Lee all contribute brilliant performances (well, Jeff Bridges is a bit wooden, but the others are great).

The main reason it has such a lasting impact, I think, is because it’s as magical and enrapturing as it is terrifying. It isn’t just scary for the sake of being scary – it’s dark, and difficult, but says something far deeper in the shadowy parts of this film. Personally, it was my introduction to the genre of folk-horror, one of my favourite film styles to this day.

Some moments stand out – as per the following (spoiler alert):

In order to save the Unicorn from the Red Bull that has been purging her species, a fledgling magician turns her into a human. It’s a fairy tale trope – a magical creature turns into a human. It’s usually exciting, triumphant, a high point in the arc of the story.

But instead her other companion begins to sob hysterically. ‘What have you done?’ the woman cries, again and again. ‘You’ve lost her! You’ve trapped her in a human body. She’ll go mad!’

The Unicorn, now a human woman, stumbles, seemingly too bewildered to cry. Her new mortality is a curse, ‘I wish you let the Red Bull take me … I can feel this body dying all around me!’

She spends the rest of the film trapped in her human form, using a fake identity to take refuge in a nearby castle. While the residing prince quickly falls in love with her, she is progressively losing her mind. She begins to forget why she came, who she is, what she is – and why she’s in so much pain.

It’s hard for a child to really grasp that this character is longing for death. But even as a child, I understood that it was terrifying that for the Prince this was simply a love story – and for her, it was a tragedy.

Its beauty is in its complexity. Characters are neither good nor evil – they are shaped by their circumstances, and warped by their desires. They’re both beautiful and ugly, scary and friendly. The Unicorn herself isn’t the heroine we recognise – she’s an immortal being, deeply vulnerable and impossible to kill.

You can see 40th anniversary screenings of The Last Unicorn at Cinema Nova in Melbourne until Wednesday 21 September.

More dark animated films, for adults and children alike

Want to find more children’s content that feel like fever dreams? We’ve got you covered:

The Thief and the Cobbler (1995)

An infamous cult film with an incredible story of technical innovation, endless production-complications and unrealised potential, The Thief and the Cobbler is the most fascinating animated film you’ve never seen. Existing in multiple finished variations, many of the sequences in this film are based on the mind-melting art style of MC Escher. It’s as beautiful as it is bizarre, and absolutely vital watching for animation fans.

The Black Cauldron (1985)

Oh, Disney – it’s hard to believe that you were even capable of making a film like this once. The Black Cauldron is one of the darkest tales that Disney has ever produced, releasedjust a few years before The Little Mermaid and the onset of the company’s ‘Golden Renaissance’. The Cauldron, The Horned King, the skeletal army that emerges from dungeon graves to sweep the world in darkness … the bevvy of dark fantasy featured in this tale is nothing short of nightmare-fuel.

Coraline (2009)

There’s a great quote from Neil Gaiman about his novella, Coraline. ‘Children react to the story fundamentally as an adventure. They may get a little bit scared, but it’s an ‘edge-of-your-seat, what’s-gonna-happen-next, oh scary!’ thing … However, adults get scared. Adults get disturbed.’ Director Henry Selick’s (The Nightmare Before Christmas) adaptation captures this skin-crawling, liminal space perfectly.

The BFG (1989)

It can be charming at times but one has to wonder, when animators were designing 1989’s The BFG‘s giant-characters and action sequences, whether they were intentionally trying to upset their viewers.

James and the Giant Peach

You know what, this one doesn’t even need a description – just watch The Rhino sequence of James and the Giant Peach, and let it do the talking.