All-time top ten box office lists are strangely fascinating. They are generally pretty similar between Australia, the United States, and the full international results. Number nerds have to read them carefully; doing a precise comparison is tricky because currency conversions and inflation have to be calculated, and Covid-19 is a huge external factor.

Avatar, Titanic, the Star Wars and Avengers franchises keep showing up in all these lists. Unlike the others, we in Australia liked Bohemian Rhapsody, while the Americans voted for E.T. but these are not earth-shattering differences. Unsurprisingly, none of the top ten Australian productions show up in the lists of all time financial greats.

Some Australian features do well internationally, and go into profit much more than our public and politicians believe, but they are not home grown independents – they are all connected to the US studio system. Without this, films like The Dry and The Dressmaker, or Last Cab to Darwin and The Castle, don’t break through internationally. And we have a lot of nifty films which should have done better and did not, even if the budgets are low and the stories are domestic and friendly.

I’ve been looking at the top ten lists for animation. The top international and US slot goes to Frozen. It has been pipped at the post in 2019 by the remake of The Lion King, but even Disney claims it is not a true animation, so we will stick to Frozen.

Animation anomalies

But something very interesting happens when we look at animation. At first glance, the worldwide list of the top-50 animations since 2000 is completely dominated by American films; the only foreign film is Ne Zha, and all but $14m of its $1.086 billion box office came from China. Almost every film on this list is a computer animation while 34 are franchises. [All figures in AU$].

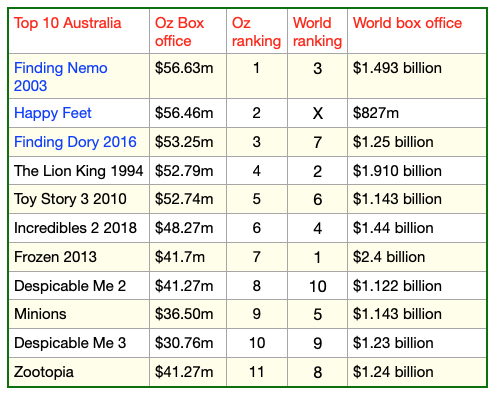

What happens when we look at the list of top grossing animation films in Australia? Most of the titles are again similar, but they turn up in different positions. Our top is Finding Nemo, but the world preferred Frozen, which is at number-seven on the Australian list.

Bear with me, as I explore the implications of this chart.

Top ten animations in Australian box office –

Look at the top three in Australia, fetchingly emphasised in blue.

We like Happy Feet much more than the rest of the world, but it still made $827m. Finding Nemo and Finding Dory were made by Pixar, and we took them to our hearts more than US audiences did.

There is a clue to why in a 2017 Screenhub interview with Pixar CFO Lawrence Levy: ‘In Finding Nemo, they sent a team off for weeks to go and explore the elements of that film. It was set in Australia and so there was a team here exploring the Great Barrier Reef and really going into detail, making sketches, understanding the world they are going to create. Very detailed.’

Happy Feet 2 came in at number 147 in the international list, but still did more than twice as well here compared to the United States. It made $21.4m in Australia and a very respectable $307m internationally.

In addition, we have four films which the stats nerds don’t count as animation because they have live action human beings in them. But the producers put them through animation pipelines [like The Lion KIng] and spend the vast majority of their time creating with computers. Babe, from 1995, took $77m as part of a world total of $723m, which means it did much better here than in the US. But Babe 2 made a disappointing $185m two years later, with only $13.85m from Australia, which adds up to a budget squelch.

Peter Rabbit, ranked at 84, made $30.3m here, and $540m internationally; it did well very well in the UK, while the US was much less enthusiastic than the US. Peter Rabbit 2 had more mundane figures, halving the take for Australia, and making $60m in the US and $225m around the world. But the UK result almost doubled, and our enthusiasm was nearly three times more in Australia than in North America. However, Covid-19 distorts the numbers for the second Peter Rabbit, so they don’t mean much.

A risky conclusion

The conclusion is a bit contentious because many people would say that Finding Nemo, Happy Feet and Finding Dory have no genuine connection to Australia. They are just global blockbusters, imitating the style of all those US films that dominate the list.

There are connections but they are soft. The Happy Feet and Babe films have Australian voices. So do the Peter Rabbit pictures, though the original story world is definitely British. The fish films, Nemo and Dory, have nothing truly Australian except their locations, which don’t dominate the story.

And yet we have a strange mystical statistical bump, in which we like these films more than the normal statistics say we should. There is something about them which grabs us and we come out to pay attention. It seems we will watch anything that has a tentpole budget, but we respond more enthusiastically if there is something Australian that leaks through.

We will pay an accent and even a location. We will find a sense of mischief, or a rhythm, or a certain sassiness and watch these films, even though they have made no overt attempt to connect literallty with national characteristics at all.

We seem to be hypnotised in a strange kind of way.

Art v Entertainment

Wikipedia’s list of all time best animations extracts two more categories, for traditional and stop-motion animation, which are fascinating in their own right. The highest grossing stop-motion film is Chicken Run, from way back in 2000, with $328m, which is way under the top computerised flick Frozen with $2.4b. The list contains much more interesting and challenging films, but there are only 32 that have ever made more than $1.46m.

In a category called ‘traditional animation’ – which is code for cell animation – the top film is the original Lion King with its $1.90b in adjusted terms. Here we break out from the US stranglehold, as Japanese film Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train took $735m around the world, which made it the highest grossing film of 2020, and the most successful film ever in Japan. From Studio Ghibli, Spirited Away, Your Name, Howl’s Moving Castle, Ponya and Princess Mononoke are all in the top-50.

Amongst the 32 stop-motion animations is Mary and Max at number 28. Released in 2009 it is a vanishingly rare Australian production by writer/director/visual creator Adam Elliot and producer Melanie Coombs. It made $3.5m.