‘We found there are now twice as many production companies making drama in Australia than there were in 1999 – but together they are sharing 20 per cent fewer broadcast hours,’ said Professor Amanda Lotz from Queensland University of Technology’s Digital Media Research Centre.

‘Of the production companies with drama titles broadcast in 2019, exactly one half had produced six hours or fewer and 94 per cent produced fewer than 20 hours. So, companies are either short-lived or exist with a multifaceted portfolio of work that includes factual or feature production, or advertising and online production work.’

The research

These are headline statements in the release promoting the Australian Television Drama Index, 1999-2019, produced by the Making Australian TV in the 21st Century research team, supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Project Grant. The work was done between the Digital Media Research Centre at Queensland University of Technology and the University of the Sunshine Coast.

The report highlights the transformation of the sector over the twenty years in which the television sector pushed to internationalise, fell into the hands of a new generation of creators, and reinvented itself to become a digital industry.

The report uses data created by Screen Australia, released in its annual drama reports, with some additional searches to cover areas beyond the scope of federal funding. To go back to 1999 they must have relied on material originally collected by the Australian Film Commission. The very fact that we have a run of data covering that period is a tribute to those who fought for it.

Read: Drama report confirms the resilience of Australian screen sector

For technical reasons, Screen Australia relies on five-year rolling averages which enables it to see trends that make a difference to decisions by government and production companies. This document doesn’t use that approach; instead, it offers a twenty-year spread in time. It is a valuable comparison.

The 19 pages of the report with all its charts and comparisons should be thought about beyond the headlining we will see over the next few days. It breaks the data down in terms of production company, which is a valuable list in itself.

Questions

It will come under fire because it seems to transmit some assumptions. It tries to counter the idea that the independent sector is threatened by production going in house at the commercial broadcasters, which is oddly specific. Just because Nine and Ten don’t do now does not mean they won’t if they have the chance, and Nine in particular operates in bad faith when it classifies NZ productions as Australian.

The report also assumes that production companies need to focus on drama, and that overseas ownership is dangerous. These are issues that should be tracked, but they are qualitative rather than quantitative issues.

We really do need good research, outside the agencies and the sector. Triumphalism by governments and special pleading by guilds and broadcasters distort the discussion and encourage endless combat. But this kind of approach cannot address the serious issues. Is drama best done by specialist companies or by diversified, nimble enterprises? That is resolved by asking the creators.

We really need to ask a lot of questions about who makes our productions, and what they are making, and how our audience feels about it. Here is just one example; we are in the middle of a pivot to family drama. What does that mean? What happened to our previous family dramas? How will they change with a global focus? How does family drama relate to our television staples? These are not boardroom decisions – they are propositions about our culture.

It is qualitative research which enables us to understand the system as an evolving ecology, rather than a static set of historical trends. In a way, we can only understand our own past by seeing those numbers as the traces of decisions by human beings. I am sure that the Digital Media Research Centre would love to do those surveys; I am simply saying that attempts to simplify the system because of resource restraints are doomed to create cartoons of the actual stories.

Resilience

Resilience is the thing that comes out of this discussion very clearly, which ScreenHub has emphasised many times now. We have a dynamic, resilient sector that has navigated huge changes. There is not much point in arguing about the sale of production companies to international enterprises because it is a survival strategy. The question is: what do we gain from it and where is it going?

Read: The future of film – a simple guide

We could get a lot of junk. In that case, we will need the research base to make that claim, and the researchers to understand what we mean by ‘junk’.

We can’t afford to defend cultural atrocities on the grounds that they are good business. And we can’t piss in the wind of history. But we can expand a research-based cultural discourse that supports our creators to be inventive and authentic.

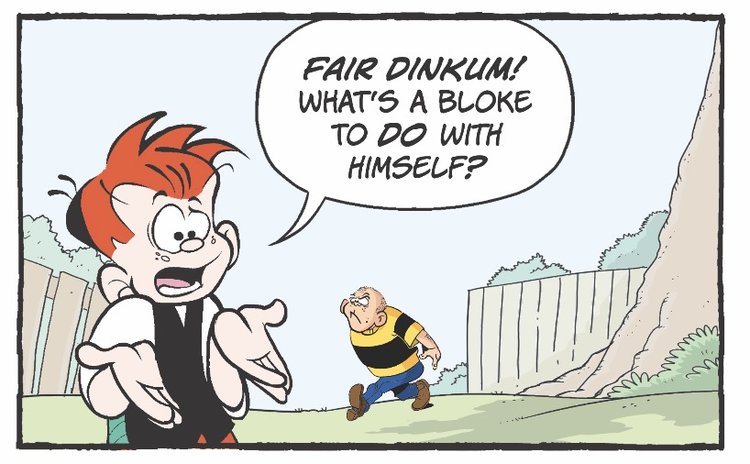

Ginger Meggs was created in 1921 by Jimmy Bancks and has become an iconic Australian character. It has been produced continuously, handed from cartoonist to cartoonist and is now created by Jason Chatfield, an Australian comedian working in New York who is the President of the US National Cartoonists Society. It is a daily feed on Instagram, and is carried by 120 newspapers in 34 countries, syndicated by companies like Andrews McMeel. Ownership is shared between Chatfield and Australian company TM Winslow Investments Pty Ltd. In 1951, the original creator Jim Bancks fought a landmark court case to control his own work.

This is a wonderful example of characters and a storyworld which is both really local and also international, in the hands of someone who is comfortable with material from different cultures. We can be artistically multivalent.

The Ginger Meggs feature film bombed at the Australian box office.