Produced to mark the 150th anniversary of the birth of Norwegian artist, Edvard Munch, and part of a year-long celebration of his life and work, Munch 150 is the second in a trilogy of documentaries screening in selected Australian cinemas as part of Sharmill Films’ EXHIBITION: Great Art on Film program.

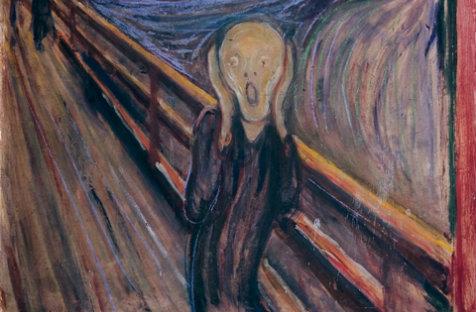

Because Norway is so far from Australia it is doubtful many will see this ‘once-in-a-lifetime show’ (as it has been billed) in its home setting of Oslo, exhibited at both the National Museum and the Munch Museum. It cannot be disputed that this one hour and 45 minute celluloid substitute about a man whose work was so important to the development of Modern Art and Expressionism is a gift for the armchair traveller, especially as Victoria’s National Gallery holds only five Munch paintings. Essentially too, the film places The Scream, the most well-known Munch painting outside Norway, in its proper perspective. One cannot but wonder if the person who paid $120 million dollars in 2012 to purchase the pastel version of painting, making it the most expensive in the world, had actually seen Munch’s other works.

Watching the film, we discover that, at the time of his death in 1944, aged 80, Munch bequeathed to the City of Oslo an incredible 1008 paintings, 15,391 prints and 4447 drawings, as well as watercolours, sculptures and a collection of written work. The responsibility for bringing this prodigious output to the public eye, lay with curators Nils Olsen, Mai Britt Guleng and Jon-Ove Steihaug who, together with other experts in their field, deliver a comprehensive exposé of the works and Munch’s often tormented life.

Unfortunately, while it is a joy to see the paintings, the family photos and views of the places Munch loved, the stilted ‘interviews’ conducted by historian, Tim Marlow, severely detract from them, set up awkwardly as they are in exhibition rooms which appear sterile and empty without enthusiastic spectators to breathe life into them. Perhaps the producers felt this would impart the dark side of the Norwegian’s demeanour and, certainly, many of the audience agreed as they left the theatre that the film succeeded in depicting Munch as a depressive personality. The interviewees were virtually placed in isolation, with the camera switching from time to time to painting, photo or scene, losing the animation which should have connected them directly to their subjects. Many intelligent people can turn to stone when they have to face a camera but this should not have been immutable for a good director. At one stage, it was puzzling to have Marlow interrupt his interviewee, a newspaper editor, mid-sentence with the words, ‘I’ll get back to you later!’

However, while the presentation may be lacking, there is no denying that Marlow, had done his homework and delivered the details well enough. The film has immeasurable value as it lingers over some of the magnificent paintings like The Sick Child, which took Munch a year to complete using a painstaking scraping technique to do justice to the delicate scene in memory of his sister, Sophie who had died from tuberculosis at the age of 14. Unfortunately, alongside other works, like Puberty and Death Agony which expose the frailty of the human condition, it was too far removed from the rigid conservatism of the time and brought criticism unbearable for Munch. As a result he spent much of his life moving from Norway to Germany and other parts of Scandinavia. It took Norwegians more than half a century to forgive him and award him a knighthood in the Royal Norwegian Order of St Olav for his contribution to art.

Munch’s life was haunted by the memories of his childhood which, though a happy one, surrounded by creative people, was finally tinged with sadness through the deaths of his sister, then his beloved mother, both victims of tuberculosis, followed by the incarceration in a mental asylum of another sister Laura. Munch managed eventually to move away from the tragedy and strict attitudes of his doctor father to the free, bohemian lifestyle prevalent in Norway in the 1880s where he found an opportunity to pour his sadness and frustrations into his art.

An important period of Munch’s work was divided into four sections under the heading of The Frieze of Life. This part of the film succeeded well, mainly because of the explanation by curator, Guleng, and better interaction with the paintings themselves. Though obviously not particularly comfortable having to ‘stand and deliver’, Guleng imparted her respect for Munch’s desire to have the paintings grouped under the headings of Seeds of First Love, Love’s Blossoming and Demise, Angst, and lastly, Death as a continuum, each subject an integral part of the next phase of life. The paintings are thus exhibited without frames, embedded into a wide, white frieze which covers the walls of an entire room of the exhibition. One of the five versions of The Scream is there, but with no special prominence, alongside many other notable paintings like The Madonna, Red and White, and The Kiss, all testament to Munch’s endless search for love through many, often ill-chosen affairs. Then again, perhaps it is the measure of Munch’s genius that, in that symbolism of loneliness and desperation which resulted in The Scream, he has created the epitome of those forces recognisable within us all.

The most memorable thing about this film is that it left the audience spellbound at the exposure of such incredible talent. It would be well worth 48 hours of flying time and a few thousand dollars to see the exhibition in reality.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

EXHIBITION: Munch 150

Directed by Phil Grabsky

Featuring Nils Olsen, Mai Britt Guleng and Jon-Ove Steihaug

Hosted by Tim Marlow

Distributed by Sharmill Films

In selected cinemas 13 – 14 July

Actors:

Director:

Format:

Country:

Release: