After five decades on the run, David Tiley, ScreenHub‘s defining editor, scriptwriter and a much-loved member of the Australian documentary industry, has finally slipped beyond the reach of the South Australian Education Department.

Read: David Tiley, much-loved ScreenHub editor, dies

Born on 30 July 1950, to a Royal Navy family, he was far too deaf to be at risk from the Vietnam draft, but simply refused to go to the local post office to register. He was on the wrong side of the law but not, he reckoned, at any real risk.

It was the South Australian Education Department that David feared.

In 1968 he had accepted a teacher’s scholarship to study film at the then shiny and new Flinders University. Under the scheme he promised to teach, for two years, wherever the state decided to send him.

They decided to post him to Ceduna.

As David told the story, he drove his car to look at the school and the teachers’ accommodation, then got back in his car, returned to Adelaide, and booked a flight to London where he got work as a researcher and documentary writer with a government organisation called the Central Office of Information.

He was in Adelaide, though, for what would, in retrospect, be recognised as one of the founding moments of the new Australian film and television industry. Accepting – as he would later describe it – the unaccountable charity of the recently-founded South Australian Film Corporation, while gaining a lifelong expertise in the refrigeration of agricultural insects from the CSIRO Film Unit. (Room-temperature insects won’t hold still to be filmed, so they need to be cooled down for the camera. The optimal cinematic temperature apparently varies for each species.)

Along with others, in 1975 he also founded and wrote for a “What’s On” magazine called Get Out and began his lifelong habit of not throwing anything away.

He still had the problem of being on the run from the Education Department, and imagined the consequences of being caught to be severe – either two years teaching in Ceduna, or having to pay back his scholarship.

The solution David arrived at – he said, years later, over a beer – was simple, straightforward and eccentric. He needed a freelance lifestyle, and he mustn’t, ever, lodge a tax return. If the tax department didn’t know where he was, the South Australian Education Department wouldn’t be able to find him. So he didn’t.

But as everyone who ever worked with him as a writer, editor or script editor knew, David’s most valuable asset was his ability to spot a weakness in the script and find a way to fix it.

So he knew that his clever plot had one potentially fatal weakness. It was possible – there was at least an outside chance – that the Australian Tax Office may (at some unforeseen and unknowable point in the future) become aware of his (some may call it criminal) lack of activity, and that the consequences may be a damned sight worse than a couple of years in a classroom.

So, while writing award-winning films like Black Gold, Kindred Spirits, convincing Tasmanian university students that their metal piercings needed to be removed (Stories From The Stone Age), ‘pick[ing] small caterpillars from the cylindrical gooplined chambers in which they live’ and directing the oddball Murphy Was An Optimist. (His lifelong friend, Russell Porter, says that film ‘wove together two apparently irreconcilable and unconnected worlds: that of a political community theatre group and the logistics behind running a complex railway network. It featured the driver and commuters on the 7.13am train from Frankston to Melbourne while the theatre group performed their agitprop around the shunting yards. It was, as a concept, brilliant and surreal, but sadly largely unseen. I fear both the title and the links went over the heads of most viewers.’) Meanwhile, David was also less-than-meticulously collecting receipts proving his expenses.

Collecting may be too strong a word. Filing would definitely be inaccurate. Keeping may be more appropriate.

Interleaved with early drafts, tucked away with ideas for shows that never got made, there were receipts. Logical protection against an evil day that may one day arrive.

And it did.

David had prospered with the years. He and his partner were paying off their beloved house at Wye River on Victoria’s Great Ocean Road.

In 1996, at the age of 46, he had finally taken a proper job with the Australian Film Commission. As a project officer (the AFC’s equivalent of development executive), he had, as he happily described it, ‘discovered the joy of spending someone else’s money’. He was respected and often loved for the time and effort he lavished on almost every film or program they funded – most of them being documentaries. He understood that every filmmaker held a deep commitment to their project, and he honoured that by committing just as deeply.

Following the AFC, at the turn of the century, David worked for Cinemedia (aka Film Victoria), project managing the pioneering ABC and SBS Multimedia Documentary Accords, as the industry began adapting to the first wave of changes brought by the internet – some of the first non-linear interactive documentaries being the outcome.

At first it wasn’t obvious, but his partner was suffering from the onset of mental illness. When it did became obvious, David discovered that she had run up debts, and been hiding the increasingly threatening letters from the bank. He had become the carer for someone he loved, but who would cheerfully microwave the ice-cream.

When the Multimedia Accords were not renewed, his contract expired with Film Victoria.

And he came to work, as editor, for a tiny, under-capitalised online publication called ScreenHub. It was a job he would keep for the next 20 years.

Fantastically fit from a lifetime of cycling, with round glasses and a short straggling beard, David somehow always managed to project an air of fragile dishevelment, as if a puff of air would waft him out the window. He was a small grey figure peeping over the top of a large computer screen, frequently sniggering as he wrote yet another joke, and never reading them aloud – he wanted you to find them and enjoy them on their own terms.

David’s intellectual range was wide, his grasp of the detail of global film policy was extraordinary, and his love of the craft of screen production was unbounded. He was one of the great interviewers. Busy international filmmakers would book a 15-minute slot with David and find themselves, two hours later, happily discussing André Bazin and the mechanical reproduction of reality. The articles he wrote were, as he liked to say, ‘intellectually chewy’.

It was also at ScreenHub that the long saga of flight from the South Australian Education Department came to an almost-end. The crumbling remains of decades of receipts were somewhat-less-than-reverently disinterred, and put together to provide a “get out of gaol almost-free” card with the Australian Taxation Office.

ScreenHub was behind the paywall and cutting edge at the time in delivering the latest film and television industry news three times a week by email. And those emails had an astonishingly high open rate – because David Tiley was an incredibly funny bastard.

Film and television industry professionals opened those emails to see what new outrage David had committed in that day’s headlines. Who had he gently mocked? Which sacred cow had he goaded? The news was also well-informed and accurate. David had a lifetime’s worth of good friends who were always willing to talk to him (often, it has to be said, for hours) – but it was the humour that got the emails opened.

Every day he came to work and made people laugh, then went home to the grim business of life.

That humour, generosity of spirit and insight, gradually transformed our friend from a filmmaker into a much-loved industry figure.

When his partner was finally moved into supported aged care, many of us hoped that David would be free from the weight that he had borne for a long time, but soon after, he was diagnosed with an incurable lung disease that slowly, inexorably, began to kill him.

Although his finances had recovered from the depths, he worried constantly that, living in rented accommodation, he wouldn’t have enough for retirement, so he kept working until he was 72.

A good story needs a surprise ending, and the long saga of David’s flight from the education authorities delivered one.

He called me to ask for advice. The Australian Government had accidentally deposited $100,000 into his account, and he was wondering what to do about it?

It was superannuation that had been lost, somewhere along the path of his long flight from justice, and it was enough to put his mind at something approaching ease.

He died, unworried by money, and secure in the love of many, many friends.

He was a passionate writer, a dedicated champion of Australian documentary filmmaking, and a gifted storyteller. But his greatest gift was for friendship, and he gave it freely.

Unless you were a South Australian Liberal of course, in which case you could go f*** yourself!

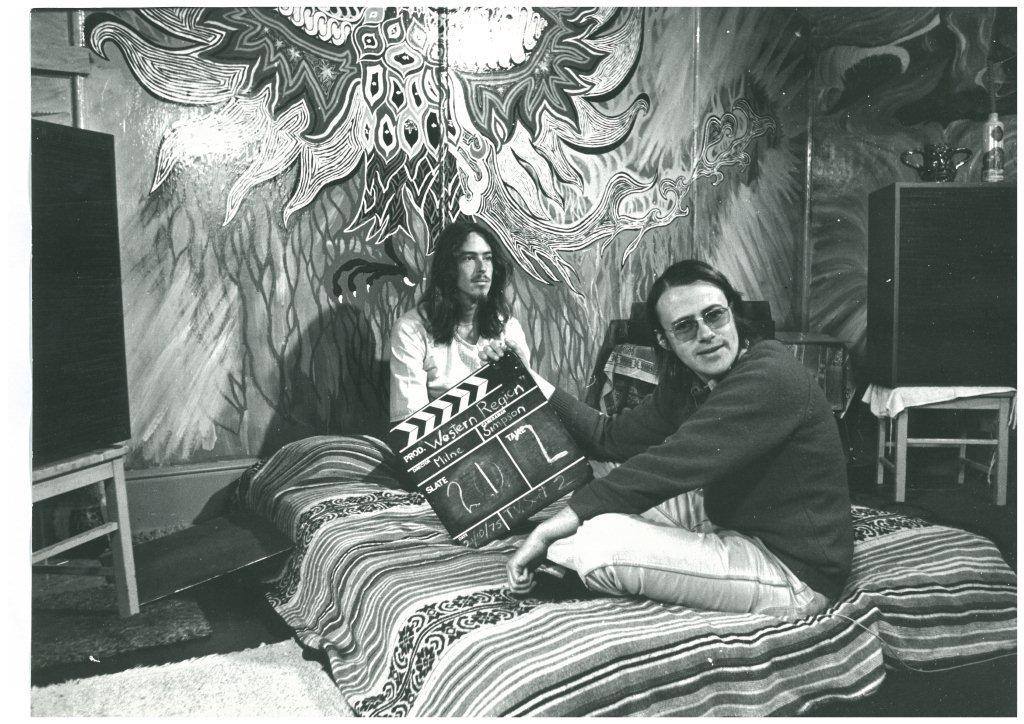

Editor’s notes: The photo at the top of this article was sourced from David Tiley’s Facebook, where it was accompanied by this typically Tiley caption: ‘Made round about 1975, shot mostly in Ceduna, called ‘Western Region’. I would love to know what happened to the people in the film. Who is this person, for instance? He was a teacher at Ceduna Area School and I somehow doubt he stayed in the profession.’

Tributes and outpourings of love and affection for David, from all reaches of the screen industry and beyond, can be found on his Facebook page, and here is a reel made by ArtsHub’s Danni Petkovic, which captures some of the spirit of David as a colleague and friend in recent years.

Here is the link to the acceptance speech David made upon receiving the 2022 Stanley Hawes Award from the AIDC. Classic Tiley.